May 30, 2005

Mapping What We Know We don't Know

Mapping Great Debates: Can Computers Think? is an interesting attempt to map the arguments and counter-arguments in the AI debate in the form of 7 poster-sized argumentation maps. Positions and arguments are represented by boxes, linked by arrows shoing how they support and dispute each other.

This is a very good idea, although the space and layout requirements for many interesting debates might be extreme (imagine a capitalism-marxism map) even at this kind of overview level. Some of the other applications mentioned in the To Think Bigger Thoughts lecture by Robert E. Horn such as GMO safety would also fit this kind of map very nicely. The only problem is that in this case the debate and science is moving so quickly the map would need to be software and easily updateable, in turn making it harder to get the high quality physical overview you get from a poster. Information walls are wonderful things, but few can afford having a huge hi-res monitor cover a wall. Sure, a web might do the job, but much of the overview power is lost. This can be seen in the still wonderful consciousness debate map. Here the debate becomes neatly divided into sections one cannot initially see the shape of. It is even worse in the GMO map, which however has very nice literature citations.

I am reminded by the attempts to break away from the strip structure in online comics by Scott McCloud. These diagrams might be conceptually constrained by a legacy of paper and then web, which unnecessarily limits their expressiveness. It is not inconceivable that they could be published as zoomable PDF or (shudder) flash. Actually, McCloud seems to already have solved the problem. Here the debate could be turned into a zoomable information mural.

Overall I have a bit of problem with the design of these argument graphs; the focus appears to have been more on the logic and sending simple iconic messages (a very good start) than turning it into information art. The heavily lined boxes, indistinct arrow icons and colorings grate on my sensitive nerves. I wonder what Edward Tufte would do with them?

But enough quibbling, this is very good stuff. I would love to do something similar for transhumanism, helping disambiguate its various strands and internal debates.

While we are still exploring Horn's site, I would like to point out the map over

What we don't know in the science of genetically modified crops and food. It is especially nice in that it immediately suggests research programs to bridge the "stepping stones" in the dark area.

The whole dark graph reminds me of that profound (and often ridiculed) insight from Donald Rumsfeld:

"Reports that say that something hasn't happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns -- the ones we don't know we don't know."

Now we just need to invent better ways of mapping what we don't know what we don't know.

May 27, 2005

The Art of Line Drawing

This week I attended the International Conference on Sport Medicine Ethics organised by the Stockholm Bioethics Centre and the Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics at Oxford University. I of course briefly blogged about it at CNE Health, but here is the long version.

This week I attended the International Conference on Sport Medicine Ethics organised by the Stockholm Bioethics Centre and the Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics at Oxford University. I of course briefly blogged about it at CNE Health, but here is the long version.

I'm utterly uninterested in sports, except for doping. Doping is many ways a testbed of future human enhancement. It also gives enhancement a bad name, and opposition to doping is also the source of many rules that prohibit enhancing drugs. Hence the ethics and politics of doping is a highly relevant area, with many interesting issues that carry over to other enhancements.

Sports Medicine

Sports medicine itself is interesting, since it has goals that are different from ordinary medicine. As Christian Muthe explained, normal health care seeks to secure a certain level of health in a just way. Sports medicine seeks to secure a level of health conducive to athletic performance, which is a far greater level than ordinary health and with no apparent requirement to be just - here there is no rationing of health care resources. Claudio Tamburrini pointed out that sports medicine in some ways is more paternalistic towards athletes than would ever be allowed in public health care; the privacy and autonomy of the patients are infringed to a great extent by doping testing and obligatory treatments. He suggested a patient concept based on being exposed to medicine: a patient is someone who is vulnerable in relation to the medical profession, and hence a bearer of patients rights. This fits well in with a health consumer perspective, regardless of why a person gets into touch with the medical professions.

My own lecture was a brief discussion about how the development of enhancing medicine for non-sports use will force rethinks of doping and enhancement within sports. My basic argument is that use and acceptance of enhancing treatment in society is increasing (but might not become the total mainstream - it is not inconceivable to see a stable split between bioconservatives and dynamists), and that many therapies while not developed for enhancement purposes also have enhancing effects. The result is that non-athletes might get far better therapies and health than athletes, with the doping regulations isolated within an enhancement-accepting society.

Drawing Lines and the Spirit of Sports

Susan Shewin argued against allowing genetic modifications and suggested that society should actively resist their use. Her main argument was that competition would make it irrational not to use genetic doping, everybody would be forced to take it and hence allowing its use would narrow autonomy. She also pointed out that the age where such modifications were most likely to be taken would be adolescence, a period not known for its carefully weighed judgements. While her argument about the bandwagon effect likely is true (especially given Sören Holm's lecture), it is not clear to me that one can enhance autonomy by banning anything. Here our difference might be due to my more individualistic perspective.

A more serious problem, based in the relational theory she used herself, is that active resistance could also reduce autonomy. It would require control mechanisms (formal or informal) that demand compliance and punish disobedience. This would produce obedience, including a reduction in free speech and thought - daring to speak out against the official view is often seen as disloyalty to the group and draw a suspicion that the dissident might be a doper. Hence there would be a tendency to make people officially support the control, strengthening it and leading to a groupthink situation. Add to this the public choice aspects of control organisations that would have an incentive to continue and expand this regime, and you get a fairly serious narrowing of autonomy. Not unlike the current anti-doping regime, of course.

Søren Holm critiqued the idea that doping could be allowed under medical control from an economic/game theoretic perspective. The core of his argument was that if doping was allowed, there would still be an incentive to hide the fact that one had a new kind of doping since it would give oneself an advantage, and this would slow the promised benefits of legalisations such as development of safer enhancing drugs. In the end, the legalised doping system would have to get back to checking athletes anyway, not winning much. While I think his example was a bit contrived, he has an important point in that legalisation doesn't automatically solve the problems.

Åke Andrén Sandberg stated his four main arguments against doping. The key argument was that it was "unhuman" due to its risks. The second argument was that given the tax funding of sports doping would likely lead to a withdrawal of such funding and a decrease in the amount of children participating in sports. The third argument was that the rules of sport are intended to make it fun to participate in and watch, and that doping is incompatible with meaningful competition. The fourth argument was the observation that vast majority of athletes do not want legalised doping.

The fourth argument might be weaker than stated due to the conformity bias discussed above. I do not see the other arguments as insurmountable either: safe enhancements could be legalised, sports might not need tax funding, children might not need traditional sports organisations for their exercise, and it is entirely possible that one could have fun playing enhanced sports too.

Christian Lenk discussed equality of opportunity and sports. He based his talk on Boorse's concept of health ("the state of an organism is theoretically healthy, i.e., free from disease, in so far as its mode of functioning conforms to the natural design of that kind of organism") and a discussion of equality. Sport without equality of opportunity would be unfair, which might make it seem reasonable to allow enhancement to produce this equality. But he argued against this, claiming that these enhancements would just introduce new inequalities of opportunities and reduce the individual contribution to sports prestations. It was never clear to me why high technology was so inimical to equality of opportunity, nor why it would reduce the need for the athlete to exert himself in training.

Torbjörn Tännsjö examined what, beyond legality and safety, was wrong with doping. He reached the conclusion that sports has an ethos of searching for the perfect human being and allowing us vicariously share his experiences and celebrate him - quite often a position gained through genetic differences. But one could create a new ethos aiming to find where the limits of the "new human nature" go, combining the enjoyment of competition, admiration of the science involved and see the athletes as testers of this new condition.

Transhumanism and Sports

Michael McNamee from University of Wales Swansea attacked transhumanism. Or rather, tried to, because it is such a vague term that it is hard to do a real philosophical critique of it - the transhumanist can always claim the critique doesn't apply to this particular brand of transhumanism or the current version. I think transhumanism needs a lot of good criticism to shape up, so I enjoyed his talk immensely.

The key problem in his opinion is that transhumanism follows the logic of expansion but has no clear aims. The object of enhancement is "better" posthumans, but the value scale is often undefined. This produces a "slippery slope to an arbitrary destination". I think he has a good point, even if I look at it more positively. The lack of clear value scale is largely due to the broadness of transhumanist views and the scarcity of solid philosophical systems. I would claim that the system embodied in the extropian principles (together with the encessary liberal-humanistic context) does define a direction to move in and ways of discerning certain "enhancements" as undesirable. But current transhumanism is indeed rather mealy-mouthed about what we are aiming for, perhaps to avoid upsetting anybody. That is probably not a good thing.

The worry about a "slippery slope to anywhere" as worse than a slippery slope to a bad outcome is interesting in itself. There is a pendulum movement between fearing too great order (1984, Brave New World, Colossus: The Forbin Project) and fearing anything-goes chaos (Our Posthuman Future, Enough). The first was a very modernist fear, this might be the postmodern variant. Maybe it is the result of the realisation that one can never achieve total order, and people instead fear that chaos will overwhelm us. In any case, the freedom pathos and open-ended dynamism of transhumanism does nothing to reassure people that we are not headed for some kind of posthuman singularity mess.

One of his criticisms of transhumanism was its attempts to normalise its aspirations through sports. If people enhance themselves (or are allowed to do it) in sports, we can claim "look, it is acceptable, now let's do it in the rest of society!". I'm not entirely sure this is true, since it seems easier to get enhancements accepted outside sports than inside. He made the point that posthuman sports might be rather pointless to watch, especially if the audience had no chance to themselves become posthuman or even identify with the posthumans. Of course, one might just shrug and ask why that would matter? In that case humans would want to watch human sports instead. Given that people also like watching monster truck racing, it seems at least some find looking at non-human sports interesting.

The worry that humans would have a less moral standing than posthumans came up. While I can see a sociological possibility, it is not clear to me that there is any philosophical problem here. As I see it, moral standing comes from being an entity that is able to act morally, something which requires abilities such as memory, rational thinking, control over one's actions etc. (whether one should include consciousness, the ability to suffer etc is more unclear to me) But once a certain level of such abilities are reached, further enhancement of these abilities does not confer a higher moral status to the entity. A smart person is not judged as inherently morally superior to a stupid one because he can predict consequences of his actions better. I would call this a kind of "moral Church-Turing thesis": there exist a threshold level of ability that allows full moral subjecthood, and all entities above this threshold could in principle reach the same moral conclusions and moral behavior (given similar data, values etc). Some might have a hard time doing it, of course.

Julian Savulescu defended enhancement in sports, suggesting that they were not counter but actually in line with the spirit of sports. Sport is after all a test of ability and talent in a rule guided activity, where we want to see the human spirit developed to its fullest. But isn't the human spirit striving to be better, to live better lives? And for that we always use technology. He recognised safety and the nature of the activity as reasonable limits - no need to allow damaging substances or enhancements that make the game ridiculous.

I think he has a good point here. What sports really is about is autotelic behavior, seeing somebody make the most of one's potential or push beyond it. There is nothing inherently wrong in doing this with technology (especially given the external technological enhancements like fiber glass vaulting poles and shark-skin swimming suits that are already accepted). Achieving something with the help of an enhancement is just as authentic as achieving something lesser without an enhancement: the enhancement allows us to have authentic experiences of greater events that we would otherwise not have access to.

One interesting point was his suggestion to have an independent body test the health of athletes, rather than just look for doping. This fits in with the conflict of interest problems of sports doctors (who are they working for?) and would aim for better outcomes in sport.

Jim Parry talked about supplementation, another grey area. Lots of interesting facts, but few conclusions. Overall, the placebo effect might be a very strong factor in much performance enhancement.

Nick Bostrom discussed status quo bias in bioethics: when a proposed enhancement seems to have negative long-range effects, are these due to real problems or just that we tend to prefer the status quo? He suggested an ingenious thought experiment to subtract the bias. I think his approach is somewhat tricky to apply in many cases, but still a good argument.

Andy Miah discussed the different kinds of possible enhancements. What are the differences between designer steroids, plastic surgery (so far allowed in sports - but what happens when some swimmer gets webbed fingers?) and morphological enhancements like wings? His suggestion is to look for "the wrong kind of risk" - some risks are acceptable in sports, others aren't. This is largely determined by the spirit of sports (and other factors, like liability, I would guess), and could be a basis for drawing lines. For more, see his Bioethics and sport blog.

Kutte Jönsson approached the issue from a radical genus perspective. Given the gender inequalities in sport and how they are institutionalised, he suggested that cyborgization (in Donna Haraway's sense) was needed to liberate women in sports. Very fun - equality through singularity. But while I think the gender dichotomies in the long run are likely to dissolve when we get good morphological freedom, it will be quite a while.

To sum up, this was a very enhancement-friendly discussion. While there are clearly practical problems with allowing enhancements, the philosophical case about whether they are inherently bad is far from settled.

The image on top of the page is a Dihydrotestosterone Receptor, based on the PDB file 1T5Z.

May 26, 2005

Saving Sweden from the Doom that Befell Stockholm

[q-bio/0505044] The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of a highly contagious disease in Sweden

[q-bio/0505044] The effect of travel restrictions on the spread of a highly contagious disease in Sweden

A preprint dealing with how a SARS-like disease might spread in Sweden, and how banning long distance travel could reduce the outbreak.

The outbreak scenario starts with a single infected individual in Stockholm. People move between the categories S (susceptible), Latent (infected but not infectious), I (infectious) and R (recovered and/or immune) with different probabilities, and are assumed to move around based on travel intensity data (from a 2002 study looking at how many people travelled between different municipalities). Three different levels of infectiousness and three levels of travel restrictions were tested - free travel, a ban on trips longer than 50 km and a ban on 20 km trips.

The results were fairly robust: even banning 50 km trips kept the outbreak largely within Svealand (the region around Stockholm) regardless of infectiousness (worst case scenario had tens of thousands infected in Stockholm, the best still a few thousand). Cities far away from the center of infection like Gothenburg and Malmö were well protected.

Is such a ban doable in practice? Legally it seems the government does have the authority to do it in the case of a potentially serious epidemic. Shutting down flights, inter muncipality bus-lines and passenger trains is fairly easy to arrange (after all, they tend to shut down spontanously from time to time :-) Northern Sweden would be hardest hit (long distances between cities), but would also likely avoid infection altogether.

The interesting thing about the study is that it shows that something milder than a full quarantine can limit the spread of an epidemic. This is an approach that does not rely on absolute protection, but just reducing the number of high-throughput links in the disease transmission network. While preventing epidemics might be one of the most legitimate uses of government coercion around, one would prefer to reduce the amount of coercion needed.

It remains to be seen if this approach works in other countries. Sweden has a fairly small population and few metropolitan areas, and intra-area transport is about 2.6 times bigger than inter-area transport (based on the data below). A more evenly populated country with stronger people flows might be harder to handle. But I would bet this is a scale-free result: another country might need another cut-off distance, but by cutting the long-range links first the epidemics is nipped in the bud.

There is still the problem of handling the core epidemic around the initial person; maybe a similar approach but on a smaller scale would work here?

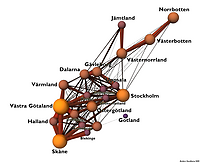

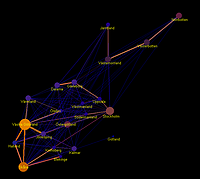

There are some cool graphs in the paper of intra-municipal travel intensities based on data from SIKA. I couldn't find the exact data, but as a consolation I plotted the tonnage of goods transported by road between the counties in the graph at the top of this entry. Color and line width proportional to tonnage, volume of the spheres represent intra-county transports. Note that the translucent arrows allow one to (waguely) see in what direction the goods flow (e.g. Norrbotten sends much less goods to Västerbotten than vice versa).

Originally I did a 2D version using Matlab, as seen to the right. However, I couldn't sleep tonight (honest!) thinking about how bad it looked.

May 23, 2005

Long Names for Very Small Objects

Before me lies an Onlifrag Housacculicorn whitcurrcruncotherlik and Nelifrag Tablestabscrach graycylishinotherlik. Thanks to The Collier Classification System for Very Small Objects I finally have names for the little things that accumulate everywhere.

I am reminded by the "The Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge" classification of animals written about by Borges in "The Analytical Language of John Wilkins":

- those that belong to the Emperor,

- embalmed ones,

- those that are trained,

- suckling pigs,

- mermaids,

- fabulous ones,

- stray dogs,

- those included in the present classification,

- those that tremble as if they were mad,

- innumerable ones,

- those drawn with a very fine camelhair brush,

- others,

- those that have just broken a flower vase,

- those that from a long way off look like flies.

That essay of deals with a conlang that tries to be its own categorisation system, gently poking fun at the absurdities and arbitrariness of categorisation. It is a nice complement to the criticism of ontologies I blogged about earlier. May doesn't seem to be a very ontological month.

May 22, 2005

Visualising the Eurovision

[physics/0505071] How does Europe Make Its Mind Up? Connections, cliques, and compatibility between countries in the Eurovision Song Contest (via Nature)

[physics/0505071] How does Europe Make Its Mind Up? Connections, cliques, and compatibility between countries in the Eurovision Song Contest (via Nature)

A nicely lighthearted paper about network analysis of the voting patterns in the Eurovision Song Contest. To nobody's surprise there are nonrandom patterns, like the Scandinavian countries voting for each other and playing tit-for-tat games.

Although I didn't watch the contest, I couldn't resist making a graph out of the 2005 data, shown above. Color of the nodes represents total score (mapped, somewhat gaudily and uselessly onto hue: blue is highest, red lowest - see The End of the Rainbow? Color Schemes for Improved Data Graphics for some color schemes I ought to have used) while points given are shown as the saturation of the blue arrows.

Analysing the contest data seems to be a popular pastime among researchers. Cultural Voting

The Eurovision Song Contest by Victor Ginsburgh and Abdul Noury looks for vote trading and the effect of linguistic and cultural similarity. The data can be used for a cluster analysis tutorial and visualised in various ways. Overall, the voting cliques seem fairly robust, while the dynamics over time is much more uncertain.

May 21, 2005

Cockroaches Having a Ball

From Slashdot: Garnet Hertz: Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. Controlling a robot by using a cockroach moving on top of a trackball, based on light signals.

This kind of research isn't that radical (compare that with running robots with moth antennae, a lamprey controlled robot, remote controlled cockroaches and rats). But it is still charming in a way, especially as a private research project.

What I especially liked was the answer to the question "Is the cockroach in pain?":

Madagascan Hissing Cockroaches make a loud "alert hiss" when they are angry. They also enjoy feel safe when crammed into a tight space. Their cuticle has no nerve endings in it. Because of these reasons, and because they do not illustrate a fearful hiss when controlling the robot, it is my opinion that they are in no pain, and do not mind being in the robot system.

This is the first time I have heard of an invertebrate experiment where one can actually tell what the animal "thinks" about the experiment. Maybe one should actually aim to use more species that are expressive enough to signal like or dislike in order to construct more ethically solid experiments?

Another good observation on the page is that "The quest for artificial intelligence or artificial life might be more interesting if it was less artificial". I fully agree (and this is IMHO becoming more and more accepted wisdom in the field): most of our experiments have dealt with environments (be they knowledge spaces or simulated worlds) that were far too clean and simple. Much of the wonderous complexity we see in nature comes from interacting with other complexity.

There is of course a reason for keeping experiment worlds clean: without it data from the experiment becomes more unreliable, and some complex responses might not be due to the system being studied itself but rather from the complex environment (however, this is interesting in its own right - quite a bit of our own complex behavior is likely just simple responses driven by complex inputs). One reason sociology, psychology and economics are such a mess is that it is nearly impossible to do unequivocal experiments. However, a simulated world can still be far more regular experiment-wise than the real world where nothing can ever be replayed perfectly.

In the end, it might be interesting to figure out ways of using this project so that the cockroaches can actually achieve their own aims rather than just move the robot around. Imagine cockroaches moving their robots to find shelter, food and partners for themselves, perhaps in ways that go beyond what could be achieved by a normal cockroach, e.g. in climates inhospitable to them. That would be truly "ecological robotics". The cyborg cockroaches would have arrived, and as long as they can't build any robots of their own we would be safe.

May 19, 2005

Information Art and the Third Internet Stage

I recently ran into the information aesthetics weblog. What a delight! It links to just the kind of information-as-art projects I enjoy, with many intriguing ideas.

After reading Ontology is Overrated: Categories, Links, and Tags and being presented to del.icio.us I was really primed for this. Because many of the most impressive projects are based on this tagging idea: there is lots of unstructured data around, and it can be visualised and made useful/beautiful in new ways. Information visualisation of the traditional ontologies and databases remain useful but clearly limited.

We have reached a new situation on the Internet, the "third stage" (I better invent a cooler buzzword here, so that I can spend my time lecturing about it :-)

The first stage was the development of the physical infrastructure, basic protocols and software services such as the WWW. It was about building the underpinnings of the net and exploiting them directly. Some meta-services emerged like mailing lists, paving the way for the second stage.

The second stage occured when more people got online and began to set up businesses, organisations and social activities online. It started with the popularisation of the web, continued through the dotcom era and could be said to have loosely ended with the emergence of blogs, the wiki and similar community tools. The hardware and core software was in place, now data and relations were added. Many new services were added to help this process.

The third stage occurs when there is enough easily accessible (and enterable) content on the Net. When you can mine Google, the wikipedia, Flickr, map databases or news you can start to build applications that make use of the massive amounts of contents that already exist. In the first stage there were almost no content. In the second stage content was added, but most of it clearly belonged to a particular organisation or site and could only be used in a particular way. Now it has become fluid.

Just look at what happens when you have a massive photo collection with some personal data and tags: it can be mapped physically in various ways, mapped socially (again in many different ways), turned into a collage, produce lettering and as an emergent ontology. Most of these things are just experiments and games yet, but no doubt many of these will grow up. Even better, with accessible APIs there will be a continuing stream of innovations as people invent new things.

This kind of free experimenting is perhaps the best way of defining the stages: in the first stage people experimented with the hardware and protocols, until they settled down. In the second stage experimentation was in content and organisation. The current battles over Net-freedom and intellectual property are in many ways signs that this stage has ended. But the third stage involves experimenting with combining contents, be it new ways of extending wikis to mapping blogs. Of course, previous stages still have influence and can help or hinder - a strict IP regimen might for example undermine flickr-like projects.

This stage is not just active on the net but in other technology too. The spread of mobile phones with cameras, digital cameras, GPS units, RFID and wireless computing is making it very much a part of everyday augmented reality. One fun project I saw was Traces of Fire, which used radio tags inserted into cigarette lighters "lost" on pubs to track the movement of their new owners. A bit of David Attenborough meets George Orwell. Another visualisation with some similarities is the group behavior visualisation from the MIT reality mining group, which tracks people on a map using their cellphones.

As I see it, the keys to stage three are:

- Large amounts of data with tags. This is often provided by online communities and automatically holds social significance.

- Good APIs to datastores or webcrawling making it easy for people to invent new tools.

- Wide online access for people and devices, making it easy to enter new data especially when stimulated by the applications.

Now, what about stage four?

May 18, 2005

Implanted debate

Today my CNE blog entry was about EU views on smart implants. The European Group on Ethics in Science and New Technologies (EGE) has released an opinion which I (of course, since 'me too!' is so boring) partially disagree with.

The big disagreement I have is of course about the ethics of enhancing medicine. While the report doesn't per se take an anti-enhancement view it worries about negative social effects and bad effects on human integrity: "the EGE makes the general point that non-medical applications of ICT implants are a potential threat to human dignity and democratic society."

The human dignity issue is complex but very important. Human dignity is involable, which implies that it is not just a boundary on other's activities relative me, but also a boundary on the freedom of my choice. I mustn't damage my own human dignity, and ethically it is proper for others to prevent such actions. I roughly agree with this view, rephrasing dignity as my self-determined inner life. Not even I have a right to remove my free will or damage my ability to act morally.

But it seems this kind of report presupposes a particular kind of human dignity that is very essentialistic and incompatible with enhancement. There are other humanistic concepts of human dignity that are far more compatible with modifications of the human body.

It is by no means clear that the protection of human dignity in the EU draft Treaty Constitution

must imply non-modification. Of the derived rights only the precautionary principle would seem truly limiting, and interpreted rationally (rather than a ban on doing anything untested) it also gives a go ahead to careful enhancement.

The closest anti-enhancement part of the EU constitution I could see was article II-63:2, that bans eugenics, making financial gain on the human body and reproductive cloning. However, this is clearly to be interpreted in a wider context since I doubt it is intended to prevent e.g. for-profit medicine.

The definition of human dignity used in the opinion,

“the exalted moral status which every being of human origin uniquely possesses. Human dignity is a given reality, intrinsic to human substance, and not contingent upon any functional capacities which vary in degree. (…) The possession of human dignity carries certain immutable moral obligations. These include, concerning the treatment of all other human beings, the duty to preserve life, liberty, and the security of persons, and concerning animals and nature, responsibilities of stewardship.”

William Cheshire, Ethics and Medicine, Volume 18:2, 2002

contains far more assumptions and context than the EU treaty. One might quibble about the obligation part if one feels suitably atomistically libertarian, but the key part is clearly "not contingent upon any functional capacities which vary in degree" - doesn't this imply that an enhancement amplifying this capacity has no effect on dignity, just as a weak capacity does not diminish it?

The opinion actually looks at the dignity issue in a rather balanced way, raising several good issues to discuss and delineating potentially problematic implants (e.g. hard to remove, that determine mental functions, that influences future generations). While this section is quite good, strange things happens in the jump to the opinion section (this seems to happen quite often, we saw the same thing when looking at the stem cell decision in Sweden) . It is here where hidden assumptions come in and turn the opinion more anti-enhancement.

The question of ICT implants in the human body is thus located between two extremes. On the one hand, the protection of the natural human body, that is to say, the medical use of ICT implants for health care, and, on the other hand, the elimination of the human body as we know it today and its substitution by an artificial one – with all possibilities in between. Human dignity concerns the human self as an embodied self. Thus the question of autonomy and respect of the self cannot be separated from the question of bodily care and of the possible changes due to ICT implants.

The rhetoric of "eliminating" the body automatically poses enhancement as destructive and against human dignity. But enhancements aim at extending human potential, either by amplifying human abilities or producing new ones. A well functioning enhancement would not be substitution - its technological basis would be irrelevant, since it is only its function within human life that is important. It is only badly functioning body parts that call attention to how they are built.

In the opinion section the genetic (or here, cybernetic) caste society rears its head again. It is extremely common as an argument, and very weakly based - I really hope I get a chance to finish my paper about it this summer. In any case, in order to prevent the emergence of cyborg haves and human have-nots, the EGE proposes that implants should only be used to bring children and adults into the normal range, and to improve health prospects. These aims are of course fine, but what about the implants that should be banned?

ICT implants used as a basis for cyber-racism.

ICT implants used for changing the identity, memory, self perception and perception of others.

ICT implants used to enhance capabilities in order to dominate others. ICT implants used for coercion towards others who do not use such devices."

To my knowledge, nobody is interested in creating cyber-rasism, ordinary racism works just fine. Implants that are used to coerce others (or their owners) are clearly unethical under existing laws and medical ethics. Just as one doesn't need particular laws to protect children from the dangers being born due to reproductive cloning since normal laws against unsafe medical practices already cover this possibility this covers already agreed ground.

It is the second and third sentence that are really troublesome. That changes that hurt autonomy (e.g. some forms of wireheading or remote control) should be controlled is not problematic. But these sentences could in principle cover nearly any enhancement: better memory, greater creativity, recreational "software drugs" that temporary affect the sense of self or brain-computer links. Given the undercurrent of unease with human enhancement and the essentialistic human nature used, these bans could easily be applied to extensions that actually promote human flourishing or individual life projects.

The report states that

"As in other areas, the freedom to use ICT implants in ones own body, i.e. the principle of freedom itself might collide with potential negative social effects. In these cases ethical counselling as well as social and political debate might be necessary."

This is of course a very European way of handling the sticky issue, but it is a healthy conclusion. Far too many would just have raised a scary scenario and claimed that the potential for realising that nightmare justifies a ban. This way it is possible to actually discuss the huge range of human aspirations and life projects, rather than immediately turn into a rigid opposition.

Overall, this report is in many ways good news. It takes a serious look at an important emerging area of human enhancement and makes many good suggestions (especially in the area of information integrity). It is far more bioliberal than anything I would expect from the Bush administration. It actually admits that there are individuals that would like to get implants due to their value systems and rational decisions - quite often in bioethical discussions people are assumed to be passive victims of fads and pressure rather than active health consumers.

But the big battle remains the 'H'-words: humanity and health. What the EU needs is a bigger discussion about what we really mean with human dignity, and to what extent it can incorporate people with different conceptions of it.

May 17, 2005

How Functional is Functional Food?

I blogged about functional foods at CNE last week. Being an avid hedonist and (theoretical) biohacker I find the idea of functional food wonderful. But beside the regulatory problems functional foods may have other hurdles to overcome before it becomes truly functional.

Perhaps the trickiest problem is the deep conservatism people have about food. Food is not just nutrients, it is culture, lifestyle, nationality and body identity. No wonder people get aroused by food scares, buy Swedish meat even when it is inferior to imported meat and protest against GMOs. Functional food actually exploits this conservatism by making the stuff we already eat promote health, rather than go through the pills and bottles of medicine. Functional yoghurt is sold as something traditional and natural, and no doubt eating a fresh orange (with all its cultural connotations of sunny Italy and 50's ski family outings) is far more rewarding than taking an antioxidant pill.

But there is a price to pay for posing functional food as natural health: it cannot go beyond nature. Modified bacteria could in principle produce any substance desired, enabling truly amazing youghurts. Bananas could give us vaccines. In principle there is nothing within the modern pharmacy that couldn't be packaged into food. With suitable safeguards against overdoses and interactions, the function of food could be anything - from promoting health over enhancing performance to recreation, palliative care or even art. But this runs counter to the traditions most people have about food. The history of inventing new foodstuffs is rife with failures. Even teaching people to enjoy exotic foods takes a lot of time. Getting people to accept radical functional foods is going to be problematic.

There are also problems like propsed EU legislation that requires expensive and time-consuming testing for any new food additives; even if it is ten times as fast as for medical drugs it would more or less inhibit the inventiveness of functional food invention. It ensures safety, but at the price of stasis.

Of course, it might be that we need to develop a culture of ordinary functional food before the radical foodstuffs I have envisioned are possible. This can still be tricky. Quite a bit of the work on functional food has concentrated on determining effect and safety rather than the most important thing to consumers: taste. It has to taste good, and the consumers need to feel that they can communicate with the producers and understand what it is they eat.

There are so much that can be done to move beyond the old food-as-nutrient or food-as-culture. Nutritional individualisation could free us from the idea that we all must share exactly the same kind of food, and recognition of the genetic differences in taste might speed this - nutrigenomics and pharmacogenomics could go hand in hand, with gene tests helping us find what tastes best and makes us healthiest. Maybe consumer-producer communication could be extended into food-as-a-service: using modern technology consumers and producers could be more strongly in touch, responding to each other and building a sense of trust. Or maybe the solution is the extended restaurant, where we go for not just company and food, but for health and advice.

Functional foods need to function socially, not just medically.

May 11, 2005

Hot Scientific Air

Telegraph News : Leading scientific journals 'are censoring debate on global warming'

The above article deals with how major scientific journals appear to reject dissenting opinions about climate change, both by rejecting papers and by not using dissenters as reviewers for papers (which, after all, ought to be something positive: they would be far more careful in their criticism than people sharing the consensus view).

At the core of several of the stories the Telegraph article mentions is the article The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change by Naomi Oreskes (Science, 306:5702, 1686, 3 December 2004). Basically it states that there is an overwhelming consensus that climate change is due to human action. How overwhelming? Of 928 papers, none disagreed with the consensus.

This is rather remarkable. It immediately reminded me of the stories of Soviet republics where - according to official statistics - exactly 100% of the voting population voted for the Party (with the exception of one republic, where over-zealous voters did some ballot stuffing to get 110%). It is of course an obviously suspect statistic, and one can easily raise a host of doubts about the methodology and conclusion. I was at the time planning to blog about it, but then I saw somebody from LaRouche's corner of the net making the same arguments I had marshalled and I decided against writing anything ;-)

Extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof, and it is not given.

Even if one accepts the numbers it is not really clear that we can learn anything from counting scientists holding a particular view or the papers they have written. The scientific community has been and is wrong about a great many things; what must be judged is the strength of the conclusions in the papers themselves. Counting the number of scientists is a bit like looking at the number of locals at a restaurant to judge whether it is any good: it is an indicator, but little more. The reliability of metastudies is often suspect, and article counting is even less informative.

It is one thing that such a paper gets published - it was after all a Science and Society column and presumably not as strictly reviewed as the research papers. That a journal defends whatever it has printed against criticism is nothing new either - I'm strongly reminded of the Dagens Nyheter plagiarism affair here in Sweden. The social psychology of protecting the in-group is present everywhere. But one have to hold a scientific journal to a higher standard than a newspaper if it is to be regarded as saying something about scientific truth (in this case the state of the consensus, rather than the climate issue itself). One might say that the opinion section of such a journal should be judged differently, but then it becomes problematic that certain opinions are viewed as unpublishable.

While the Telegraph article does not mention it, this case is similar to the hockey stick graph affair. Of course, untangling the science from the acrimony is not always easy. There is also the problem that journals prefer to publish positive results. We really ought to publish more papers showing negative results and ruling out classes of theories, but most people want to read new or positive results: refutations are not as "sexy".

Science rejected a paper criticising the Oreske study based on that the points he made had been 'widely dispersed on the Internet'. While journals certainly should aim to publish scientific news, it is a worrying if related internet debate could prevent publication. How are we to publish rebuttals (or support) to controversial papers if widespread net discussion makes them unpublishable? Scientific publication makes a paper a part of the record, while net debate at present is ephemeral. There is a risk that this view makes truly bad papers inviolable. Only the mediocre papers that nobody reacts to can be criticised.

Scientists are of course as prone to groupthink as other humans. A fun example is hinted in the graph of the estimated age of the universe as function of publication year - the estimate undergoes a kind of punctuated equilibrium where a consensus develops until sufficiently good measurement methods forces an update (I have seen an even better plot of this, or maybe the value of the Hubble constant, that showed the conclusions of individual papers that made the groupthink even clearer). But this kind of groupthink is eventually overcome with data, and there is to my knowledge few journals that reject papers because they have too high or low values of their conclusions.

Getting the scientific publication process right is important, since it is not just the dissemination of results but also the testing of them against the experiences of the rest of the scientific community. If the journals act as gatekeepers based on the wrong kind of parameters they distort all of science.

Climate might be one of the more extreme examples, since it is so intimately tied with political action (and hence grant money feedback, stakeholder pressures etc) worldwide. Here in Sweden it seems genus theory has a similar status: officially encouraged, claiming wide applicability to other fields, refusing to accept criticism of its assumptions. In general, the more involved politicians become with funding science, the greater the risk of bias. This is an external bias, just as dangerous as internal bias due to groupthink. But groupthink thrives especially well when certain views get official recognition as "right" and subsequent support, or when resources can be directed away from troublesome researchers.

One antidote is of course to ensure that funding and academic careers are less controlled by outside interests. Having academics stand up more for academic freedom is also a good thing. That can lessen the external bias. But to deal with the internal groupthink we need to strengthen the force of peer review and open debate. I honestly admit that

May 10, 2005

More web neighbourhood maps

TouchGraph GoogleBrowser V1.01 is a charming web graph applet that I have been playing with recently.

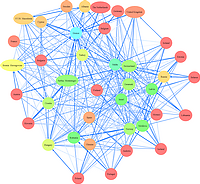

As regular readers know, I have been involved in a neuroscience education/debate project called Se Hjärnan!, organised by Swedish Travelling Exhibitions, The Swedish Science Council and The Knowledge Foundation. In the end the different groups produced several different websites: one inside the web of Swedish Travelling Exhibitions, one flash knowledgebase and a neuroanatomic atlas by C.H. Berthold (as well as assorted internal sites). How does these sites link to each other? Have we created several isolated clusters or does there now exist a "Se Hjärnan cluster"?

I used the GoogleGraph to find out by adding the URLs of the core pages in the different organisations. The results are shown below.

This is the full graph with full names. The core pages mentioned above are the orange one and the two directly to the lower left of it.

The same graph but with short names. The overall structure is visible.

A pruned version, where nodes with few links are removed for clarity. The graph still remains in one piece and the bridge is visible.

The good news is that these sites link nicely to each other, forming a core. The knowledge foundation and science council form one cluster, while travelling exhibitions form a cluster with itself due to lots of internal cross-links. The project acts as a bridge between the organisations.

Not very many external sites show up in the graph, likely because there are many but weak links pointing at these core sites. Over time I expect www.nervsystemet.se to grow into a major authority given its excellent contents once the neuroscience teachers in Sweden discover it.

I also looked at the neighbourhood of this blog:

It is nice to know where one are in relation to everybody else.