July 21, 2005

Mmmm... Time Machine Donut

Realistic Time Machine? New design could forgo exotic ingredient: Science News Online, July 16, 2005 discusses a paper by Amos Ori suggesting that one can build a time machine out of a toroid of everyday spacetime vacuum surrounded by an ordinary matter configuration. No need for those hard to find materials that violate the energy conditions.

Realistic Time Machine? New design could forgo exotic ingredient: Science News Online, July 16, 2005 discusses a paper by Amos Ori suggesting that one can build a time machine out of a toroid of everyday spacetime vacuum surrounded by an ordinary matter configuration. No need for those hard to find materials that violate the energy conditions.

If I understand the paper right the matter configuration creates a spacetime inside the torus that locally looks like a plane gravity wave; I guess the device acts as a toroidal gravity waveguide. A trip around the torus can move an observer back in time, at least after it has 'geared up' enough: the spacetime starts out normal, and then after a while (whatever that means in this context) develops a closed timelike curve (CTC).

There are several rather strong conditions preventing the formation of time machines. Ori claims to have circumvented them. To get around Hawking's theorems it seems the matter around the torus will have to become singular, perhaps forming a couple of black holes. This might be a case of "chronological censorship" (a combination of cosmic censorship and chronology protection): if the matter enclosing the torus becomes a black hole just before the CTC forms, the horizon around the entire device will prevent any time travellers from leaving. They can loop around as much as they want, but only as far as to the formation of the CTC.

So we have to wait for a more practical demonstration of time travel. Which in itself is a counter-argument to its possibility.

July 18, 2005

The Hunt for Time

In a recent report, Tidsjakten ("The Time Hunt") Stefan Fölster looks at the future of Swedish business and society up to around 2020. The book is based on interviews with 324 CEOs of larger Swedish companies and their views on the long term prospects of their businesses.

In a recent report, Tidsjakten ("The Time Hunt") Stefan Fölster looks at the future of Swedish business and society up to around 2020. The book is based on interviews with 324 CEOs of larger Swedish companies and their views on the long term prospects of their businesses.

The core idea is that time is getting more precious: saving time saves money, wasting time loses you business and employees - because the hunt for quality time is driven by an increasingly mobile and non-materialistic culture. People want less lost and uninteresting/nonpaying time. This helps companies that provide simple, working products and services. New niches emerge for packaging services and products. Robotisation will become increasingly common, moving workers to other jobs. Overall there is a trend towards decreased employment, and a move towards R&D, marketing and international projects. People rather seek freedom at work than having more spare time and more people want to work as independent contractors - it is about controlling ones own time rather than having a lot of it.

Other forecasts made are: an increase in individual customisation, high demand for health and life extension treatments (which will ameliorate the greying of society significantly), market solutions environmental problems and large investments in low salary countries, making world poverty decrease faster than expected.

Overall, it is a fairly positive image (but the TCO union representative on the presentation meeting wasn't so happy about it - and her perspective got to set the tone of the coverage in much of the press). The big weakness is that it is locked into a very typical Swedish industry perspective: what matters is making things, a technological-administrative perspective where things can be fixed by making the right laws or starting government programs. There is no mention of the importance of the creative class and the effects of the emergence of entirely new and unexpected industries - by 2020 we will have seen several such emergences.

The trend towards low-friction, fast response society seems spot on, and the recommendation that authorities should be required to have 24 hour, online access is a good one. Overall, many of the recommendations are good ones, seeking to reduce the friction and lack of choice in the system.

But the image in the report is a future fast, efficient and fun Sweden that basically works like today. In 20 years society won't change unrecognizably, but just looking back to 1985 and the differences in business, politics, morality, outlook and aims shows that quite a bit does happen. Now add the ability for people to rapidly implement their wishes and social aims (whatever they may be), and it is likely that the future will be significanly more different than an equivalently remote part of the past. Being able to handle this kind of rapid qualitative change is a challenge that requires more than just adaptability in the sense of the report.

Fölster got the importance of biotechnology and tobotics right (although there is an annoying error about the number of bacterial strains). But he places them into the traditional industrial context - new materials, producing healthcare and making things. But the real impact of robotics will be when software amplifies or replaces human skills. Even a fairly stupid digital secretary with sufficient natural language processing could displace an awful lot of clerks in the service sector doing basic paper-shuffling. Biotechnology becomes really powerful when it moves beyond mere agbio and healthcare into chemical manufacture, ecological engineering and human enhancement.

But this report is of course limited by how radical future visions can be envisioned within the framework of the Confederation of Swedish Enterprises (and Swedish debate) - it is radical enough by suggesting that culture affects business. Following its advice will help society become more adaptable, which will be needed. although I think we will need qualitative new kinds of adaptability and not just a quantitative increase.

July 15, 2005

Informed Consent Enhancement

This week's CNE blog was about software to inform patients in order to reduce malpractice litigation (since they cannot claim afterwards that they weren't fully informed). In my opinion the interesting thing isn't avoiding the suits (but that provides a good economic incentive) but finding better ways of informing patients. One idea that came up when pondering this was to use peoples' desire for ego-reinforcement to stimulate themselves to inform themselves.

This week's CNE blog was about software to inform patients in order to reduce malpractice litigation (since they cannot claim afterwards that they weren't fully informed). In my opinion the interesting thing isn't avoiding the suits (but that provides a good economic incentive) but finding better ways of informing patients. One idea that came up when pondering this was to use peoples' desire for ego-reinforcement to stimulate themselves to inform themselves.

In my experience, whenever something is done (like a reorganisation, removal of bicycles from the street or change in the laws) there will allways be a few people who come forward and accuse "but I wasn't informed!" This is more of a protection of their self-image than a real lack of information. Usually there has been several announcements beforehand, and while some might have been lost in information overload the rest were simply ignored. Afterwards the self has to be protected (and innocence claimed) by being underinformed.

In medicine this is a real problem, since it undermines informed consent. Several of my friends have described how their doctors overexplain fairly obvious (to them) issues, until they finally appear to understand it. And I have heard horror stories about patients thrice claiming not having a pacemaker before undergoing MRI scans or claiming that they had never undergone surgery when their scars clearly indicated both a cesarean and appendectomy.

In order to have a health system where the patients decide about their health they of course need to be informed. One group of active patients will inform themselves, and pose no problem at all (except when they are misinformed, of course). Then there is a group of passive patients that do not spontaneously inform themselves; they prefer their doctors to tell them what to do. This is entirely their right and doesn't invalidate health choice in any way, but this group also poses a bit of information problem.

But it is the group of patients that actively seeks treatment and yet avoids information that really will be troublesome. These are the litigators and hypochondriacs. The problem with systems like Ellie is that they require a certain amount of active self-education. Even if the doctor plops the patient in front of the computer and goes away to bring coffee, the patient might not be motivated to explore very deeply. Maybe deeply enough to make a malpractice suit later less likely, but not deeply enough to be well informed.

How can we enhance the ability and willingness to inform oneself? People in many fields have worked hard on providing easily accessible and understandable information, solving the first part. But the second is tricky.

As hinted above, I think a key issue is saving face/protecting one's self-image. A simple reson not to inform oneself is the fear that one will not understand the information or act well on it (hurting self-image). That can to some extent be handled by presenting the information as being easily understandable (or 'XX for dummies' - but who wants to be seen reading anything for dummies?).

But maybe a positive approach is more useful: make knowing the information a ego-reinforcing sign. Imagine a system where patients who have informed themselves are given special note, maybe being put in their own queue or referred to specialists more easily. It does not have to be a major difference. It could be just as first class cars on some railways are identical to the second class, but since fewer people buy first class tickets there will be a bit more space and a symbolically ego-reinforcing environment.

This is of course counter to the egalitarian idea of having a equal treatment for all in health care. But this does not happen in the first place: the more active patients do ensure that they get specialist referrals and better treatment by being active and verbal. Only in a totally mechanistic system where the doctors ignore what the patients want and do would treatment be identical, and that is not something anybody wants. The egalitarian vision seeks to ensure equality of outcome - the best treatment possible given the condition of the patient, and there patient education and activity are relevant parts. Someone who can explain their needs more clearly will on average get treatments that fit them better. The goal here is to stimulate active but less informed patients to become better informed, i.e. to enhance their own understanding of their own needs. This is not counter to egalitarian goals (unless perverted into 'one size fits all', which happens from time to time) but rather helping them along. An equality of outcome egalitarian would of course want to extend this to the more passive patients too. I think my ego-reinforcing idea above might help at least some of them to activate themselves.

So my suggestion for extending the information systems is not just to log the information that the patient has accessed the information, but add a little gold star (virtual or real) to the patient record. With enough "frequent reader lines" there might be other perks, but just having a sign that one is informed is reward enough to many.

July 09, 2005

Tubular Plots

Tubeplot for Matlab is a simple package for tubeplotting I wrote today. It allows the user to plot 3D curves with variable width and coloring, as well as to save them as Wavefront 3D obj files for further rendering.

Tubeplot for Matlab is a simple package for tubeplotting I wrote today. It allows the user to plot 3D curves with variable width and coloring, as well as to save them as Wavefront 3D obj files for further rendering.

The original reason I wrote the package was because I got so inspired by the Lexus "Brainchild" commercial by Laurent Bourdoiseau (via 'Boards). I wanted to do some similar particle effects, and began hacking together a simple particle simulator in Matlab. The result was some fun gravity simulations as well as an afternoon of playing with differential geometry and dynamical systems.

July 07, 2005

Ethical Ethnic Patenting

This week's CNE blog was about whether Millennium's breast-cancer gene patent is racist.

The background is the ongoing patent struggle in the EU where many groups want to void the patent, enabling cheaper competing tests for mutated versions of the BRCA genes. While there are some good arguments against the patent, the racist argument is downright silly: since the relevant mutations are more common in certain ethnic groups, the patent is inherently racist.

As I argued on CNE, this does not hold water. There are many ethnic variations in genetics, and patents related to such variations are not automatically racist. In fact, one should be happy for new treatments or diagnosis for illnesses - they would help the most strongly affected groups. The real problem here is of course cost: since Millennium's test isn't cheap (their high marginal business strategy has opened them for much of this storm of criticism) the cost would be paid for by certain ethnicities. One might argue that the situation is still better for them than before, when no test existed, but more importantly this cost issue has nothing to do with the patent per se. It is about business practices rather than patents and could be settled in a business law court.

We are going to see lots of patents and medicines that make use of individual genetic differences. Some of these are bound to be linked to ethnicity. If that is accepted as a reason not to pass a patent interest in pharmacogenomics is going to cool and many new treatments will not be developed. In the end we will all end up a bit poorer and sicker.

July 04, 2005

A Low Zenith Angle

Bruce Sterling's Zenith Angle could perhaps be described as "Bruce Schneier goes to Washington". It is the story of a computer science genius who decides to do the patriotic thing and help the US to fight in the post 911 cyber battlefield. Hillarity ensues, or at least satire.

Bruce Sterling's Zenith Angle could perhaps be described as "Bruce Schneier goes to Washington". It is the story of a computer science genius who decides to do the patriotic thing and help the US to fight in the post 911 cyber battlefield. Hillarity ensues, or at least satire.

Unlike the more political Distraction (the other Sterling novel besides Schismatrix I really love) this shows the landscape from the outside. The protagonist Van is never a Washington or intelligence insider, and the niches he find for his work are strange both to him and his surroundings. In the end he might be the grain a pearl accretes round - assuming the oyster doesn't expell or digest him.

As a novel I was not too impressed: structurally it is far too random and often feels unconvincing - the main character stumbles from one odd situation to the next without any sense of direction, and the real villains are introduced late and too over the top to be convincing.

But it is not as a novel about a nerd coming of age as a cyberwarrior or a strained marriage between two intelligent academics that Zenith Angle works. Where it works is as satire and critique on the world of anti-terror government agencies, lobbying and cyberwarfare hype.

Often these critical rants are extremely entertaining, such as a longish one explaining exactly why national computer security is impossible. It is bitter, it deflates Internet, the software industry, Microsoft, Linux, Wi-Fi and the whole Digital Revolution and it is right on the money (but I'm too much of an optimist to see it as a major problem).

The key insight of the novel is the similarity between the Dot.Com-bubble and the War on Terror: they are both bubbles, built from self-amplifying expectations with relatively weak connection to the real world. There are real business opportunities and terrorists out there, but their reflections into stock markets and Washington organisations are distorted and made into tools for the internal agendas.

Cyber warfare is by now hyped to death, and everybody has found new names for it so as not to sound ridiculous. I'm not entirely sure there is anything there yet; it might be a new paradigm in the making, but it has not yet crystalised into anything useful. Sterling suggests that beyond the sexy name that attracts governmentbeings (until the hype runs out), if there is anything real underneath it might be so incompatible with How Things Are Done that it will not fit into any of the present structures. Cyberwarriors might be ronin or ninjas, impossible to fit into the system and of doubtful legality. At the end of the novel, there is a hint of who might want to recruit the real cyberwarriors, and it rings worryingly true.

Bunker's prescient paper about five-dimensional warfare points out the risk the new possibilities pose for the traditional world of politics and warfare (and was chillingly demonstrated in 911), but it might turn out that it is not possible to reliably apply the insights to make the traditional world to fight back: to do so it has to become something unrecognizable. It is the new actors, or parts of the traditional establishment that are willing to change, that can build in these capabilities. But even here the principle of incompetence might rule: most will fail utterly, but we will only remember those few that actually (out of sheer luck, genius and opportunity) succeeded. This is impossible within the traditional stasist, statist mindset.

But it could also be that beyond the "new paradigms of warfighting" cyberwarfare is just a set of tools to extend policy by other means, not some new unified battlefield. SIGINT, software intrusion, games of economic-technical manipulation, ubiquitious surveillance and massive internet exploits stand open to any parts of the intelligence community, armed forces, government agencies or for that matter, corporate and private actors. There is no cool cyber battlefield, but just a huge mess with different actors fumbling about in the dark.

Sterlings brand of dark techno-enabled satire seems to suggest that both possibilities are true. Heroes and villains mess things up, and later explain it away by saying they were intending it all along.

July 01, 2005

The Poisson Process of War

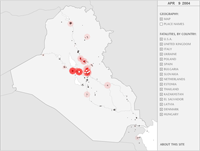

Iraq War Fatalities (via Information Aesthetics) is in my opinion one of the best data visualisations around right now. It runs at ten frames per second, one frame corresponding to a day. This way the Iraq war so far is displayed over a few minutes. Each fatality appears as a dot (size and tint denotes number of simultaneous fatalities) with an audible click. The result is that one can experience the situation both in time and space.

Iraq War Fatalities (via Information Aesthetics) is in my opinion one of the best data visualisations around right now. It runs at ten frames per second, one frame corresponding to a day. This way the Iraq war so far is displayed over a few minutes. Each fatality appears as a dot (size and tint denotes number of simultaneous fatalities) with an audible click. The result is that one can experience the situation both in time and space.

This is a very Tuftesque time-space narrative, even down to the sober grayscale-red coloring. The important lession from the data is the temporal patterns: a steady (Poisson process?) background overlaid with bursts, and no clear increase or decrease.

As a statement about a war it is on par with Minard's plot of Napoleon's war with Russia - as statistically objective as possible, damning the activity of warfare itself quietly and exactly.

It is always fun to think about improvements. Armchair scientific visualisation, all the fun without the hard work.

One idea would be to have a scrolling marker showing ticks for the fatalities. This would help support/disprove the intuition of nonstationarity.

Perhaps it would be interesting to have a scrolling timeline of other events; it might be too busy, but it would be useful to see if there are any correlations with, say, the election or statements from leaders.

It is too bad that there are no reliable sources for Iraqui casualities, since they of course ought to be represented in the visualisation. I have also pondered whether it would be a good or bad thing having differently colored markers for different nationalities. My guess is that these same color markers keeps the visualisation clean enough to do its work: having two or more hues might make the perceptual processing to cumbersome to handle the temporal data.

The strength of this visualisation lies in its clean simplicity. It is far easier to overload than to underload a visualisation. It might also be extendable to other conflicts, both as a global map or a local one: the core idea of sonified clicks and event markers leaving traces is a very solid one.