March 29, 2006

Enhancement Project Website

Just recalled that I may not have linked to the Enhance project website from here yet. It is the website of the EU project I participate in, dealing with cognitive enhancement (my part), life extension, mood enhancement and physical performance. In time the site will have an extended area with public information, papers etc. but already it can work as a brief overview of the subject.

March 25, 2006

Live Long in Order to Prosper

This week's CNE blog was about the Economic Case against Ageing, inspired both by the recent Longevity Dividend article in The Scientist (S. Jay Olshansky, Daniel Perry, Richard A. Miller, Robert N. Butler, vol. 20:3 2006) and my own letter to the editors of the Financial Times (see also Waldemar Ingdahl's take on the essay).

The basic idea is that life extension isn't just individually good, but also causes huge economic benefits - benefits likely to outweigh any costs caused by people living longer. Sure, we have to rewamp pension systems and construct a new concept of the path of life, but that is challenges far preferable to the enormous amount of suffering caused by ageing. If we could fix mortality to save the 100,000 dead each day it would be great, but even a modest gain in healthy life expectancy has a big leverage.

It was interesting to see the high noon confrontation between Aubrey and some of the authors of the paper mentioned above at last week's conference. On one end of the street the lone gunslinger Aubrey the Beard, on the other side the fearsome biogerontologist brothers. Of course, the real shootout has not yet started, this was just a few warning shots getting the bystanders to stand back. Much of the disagreement was due to the different conceptual approaches (engineering project vs. scientific study). But whoever is left standing afterwards, the idea that ageing is not immutable is going to prevail.

March 15, 2006

Tomorrow People Are Breaking Out All Over the World

I'm at the James Martin World Forum 2006. The theme is "Tomorrow's People: the Challenges of Technologies for Life Extension and Enhancement". So you can guess I feel right at home. I will update this entry with more details as the conference develops.

I'm at the James Martin World Forum 2006. The theme is "Tomorrow's People: the Challenges of Technologies for Life Extension and Enhancement". So you can guess I feel right at home. I will update this entry with more details as the conference develops.

[ Added Thursday 17: Actually, to a large extent my comments can be found on the discussion board, where I have been posting intensively. I'll add entries to this blog based on the conference later instead. ]

If there is anything the debate shows it is that human enhancement ethics is actually getting somewhere. The philosophical or sociological case for ruling enhancement out altogether is very weak even if expressed occasionally fiercely and at high government levels. Instead, we need to look at particular proposals and judge their particular problems and opportunities.

The two keynote speakers James Martin and Joel Garreau expressed the thought that we might need enhancement to solve many of our problems, and that it is likely to become widespread for its own reasons, so we better find ways of directing the development towards favourable outcomes.

March 14, 2006

Heritability of Memory

Dominique J.-F. de Quervain & Andreas Papassotiropoulos, Identification of a genetic cluster influencing memory performance and hippocampal activity in humans, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.0510212103 shows that variations in the genes for the proteins that control the memory consolidation cascade affect memory ability in humans. They even correlate with how activated the medial temporal lobe is during memory encoding.

Dominique J.-F. de Quervain & Andreas Papassotiropoulos, Identification of a genetic cluster influencing memory performance and hippocampal activity in humans, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.0510212103 shows that variations in the genes for the proteins that control the memory consolidation cascade affect memory ability in humans. They even correlate with how activated the medial temporal lobe is during memory encoding.

Starting with a list of potential memory-related genes, the researchers found seven with strong correlation to good memory encoding. These were the genes for adenylyl cyclase, PKA, CAMKII, the NMDA receptor, the metabotropic glutamate receptor and PKC. A fairly well-known list to any student of long-term potentiation.

The genetic variations were used to calculate a Individual Memory Associated Genetic Score (IMAGS). IMAGS was simply calculated as the number of memory-improving genetic variations, weighed by how much they predicted better memory. IMAGS correlated reasonably well (0.32) with long term memory performance. It did not correlate with immediate recall (working memory, attention, motivation etc), and a similar measure calculated based on some non-memory related genes did not show correlation with memory.

Human memory ability has about 50% heritability and the paper points out that 90% of the genetic variance remains to be found. So this just predicts 5% of human performance. But it is a start. Looking at the size of the effect of the genes their "power" seems fairly evenly divided, with ADCY8 and PRKACG at about 18% and GRIN2A, GRM3 and PRKCA at about 10%. If that curve were to continue there would be a long tail of other genes. But the total influence should sum to one, and the tail beyond the known genes to 0.9. That suggests to me (based on lots of squinting at figure 2 and intuition, caveat lector) that there is likely a bunch of other influential genes, but their number is likely of the same order of magnitude as the found genes - we should expect maybe 10-20 big genes providing more than 1-2% of the genetic variation, not 100, 1000 or just

one. That is half-cheering if we want to enhance them: a reasonable number of targets, but selecting for so many genes will be tricky, and enhancing individual genes will have a fairly minor effect.

March 13, 2006

Open but Discriminating Minds

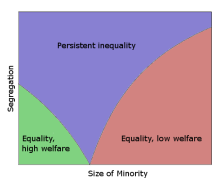

A fun little Santa Fe Institute working paper, "Social Segregation and the Dynamics of Group Inequality" by Samuel Bowles and Rajiv Sethi demonstrates how one can get inequality without discrimination (or difference in ability) due to assortiveness in social networks. It also suggests non-discriminating ways out of it, as well as some nontrivial risks of reducing segregation.

A fun little Santa Fe Institute working paper, "Social Segregation and the Dynamics of Group Inequality" by Samuel Bowles and Rajiv Sethi demonstrates how one can get inequality without discrimination (or difference in ability) due to assortiveness in social networks. It also suggests non-discriminating ways out of it, as well as some nontrivial risks of reducing segregation.

Their model is based on the assumption that acquiring human capital (getting schooling, seeking out good jobs) is dependent on the amount of human capital among one's social circle. It is not necessarily rational to acquire it if few others do, and the ease of acquiring it of course increases with the number of well developed friends.

Social networks are usually assortive: people tend to have mostly contact with people like themselves. Segregation is a measure of assortivity: at total segregation all one's friends belong to the same group as oneself, at lower levels more and more belong to the other group (the model assumes two groups for simplicity). The paper shows that given these assumptions it is possible to have one group far more disadvantaged than the other because it gets trapped in a low human capital equilibrium. It is of course a theory paper, but it shows a potential problem most attempts at dealing with inequality and discrimination misses.

The really interesting part is the analysis of what happens when the segregation is decreased. Below a certain level the unequal distribution of human capital becomes unstable and converges to equality. One can imagine a gradually less segregated society where one minority after another relatively rapidly gets assimilated in the advantaged population. Sounds good, but not so fast! If the proportion of disadvantaged is large enough, the new equilibrium will be about as bad as their original state, but now everybody is down there. There exists two different domains of equal states, corresponding to the disadvantaged rising up to become as wealthy as the advantaged, and the one where everybody ends up badly. An equal society may in itself be seen as valuable, but there are also extra benefits from a larger economy for all - it seems plausible that the general welfare decline does not appeal to anybody but the most radical egalitarian.

This seems to suggest that it is better (or easier) to integrate small groups than larger ones. Everybody wins, and reductions in segregation would be supported by everyone. In the large group case the rational thing for everyone would be to retain the segregation, but the disadvantaged group might be tempted to at least temporarily increase its welfare.

The authors point out that one way of getting from a welfare-decreasing to a welfare-increasing transition is to reduce the costs of human capital acquisition overall. This moves the borders between the different regions in such a way that it becomes easier (or possible) to get to the good equilibrium. Just improving the costs for the disadvantaged group doesn't move the border between the good and bad transitions: for small groups it becomes easier to get to a high welfare equilibrium, but if the group is too large the intervention doesn't help.

Perhaps the trickiest part is to reduce the segregation parameter. The model deals with a kind of segregation that depends on people's choice of friends and relatives, something much harder to fix than repealing discriminatory laws. The authors propose a few approaches, like bussing to create more mixed schools, but it still seems to be a tricky problem to "solve".

From a transhumanist slant the paper suggests an interesting counterargument to the claim that cognitive enhancement will increase social inequality. If it lowers social capital acquisition costs in general, it would increase have a chance to markedly equalize society! Even if the technology diffuses downwards this would work. Just lowering the costs of the advantaged group doesn't seem to change the situation of the disadvantaged group, up until the point where the technology now has become so cheap that it starts to lower costs among the disadvantaged.

It might also be transhumanistically interesting to consider whether there are technological changes that can reduce the assortiveness effect. To some extent the much broader (if with weaker links) social networks enabled by modern society and communications might be doing that. If family (which usually belongs to the same group as a person) becomes less important, assortiveness decreases. Nobody knows you are a dog on the Internet... except through your spelling and interests of course. These technologies still have a degree of assortiveness, and as online social networks are based on shared values or interests they will still have an assortive effect.

Back to Mars

I guess half of the blogosphere has reported it already, but Google has put up Mars maps with the Google Maps interface. It really warms my heart to see my old stomping grounds around New Chryse in the da Vinci crater, the forests of Terra Arabia and the former battlefields west of Ma'adim Vallis... OK, the non-geographical features are due to a lengthy roleplaying campaign I ran a few years ago (some files about it are online) set on a terraformed future Mars. The planet makes a wonderful setting, since it both has a complex geography, beautiful fantasy-like place names and is something far more concrete than a purely imagined world.

I guess half of the blogosphere has reported it already, but Google has put up Mars maps with the Google Maps interface. It really warms my heart to see my old stomping grounds around New Chryse in the da Vinci crater, the forests of Terra Arabia and the former battlefields west of Ma'adim Vallis... OK, the non-geographical features are due to a lengthy roleplaying campaign I ran a few years ago (some files about it are online) set on a terraformed future Mars. The planet makes a wonderful setting, since it both has a complex geography, beautiful fantasy-like place names and is something far more concrete than a purely imagined world.

Of course, I want to go there for real. Maybe not live there, but at least visit occasionally.

My only problem with it is that unless you are a desert buff, it will be rather barren. You need to do tremendous amounts of terraforming to give it a decent climate and biosphere. I handwaved it a bit in my campaign, but in reality even with megatech and nanotech it is going to be heavy work. Which makes disassembling it to use as materals for a M-brain perhaps a more efficient way of creating complex, new living environment (as Robert usually argues). But there is still something marvellous and worth preserving in what has emerged entirely contingently, without planning. Of course, after disassembling the planet one could have a complete model running much more efficiently in a fraction of the mass. Maybe I'm just a hopeless romantic clinging to antiquated notions of terraforming (or at least ecopoiesis).

March 07, 2006

Neuroethics, Neuropolitics

Today I attended a stimulating seminar on neuroethics here in Oxford. Each speaker had their own take on what neuroethics was, providing a refreshing mix of perspectives.

Today I attended a stimulating seminar on neuroethics here in Oxford. Each speaker had their own take on what neuroethics was, providing a refreshing mix of perspectives.

Dick Passingham discussed the possibility of advanced lie detection and whether that might threaten integrity. His reasoning was that plausible systems would be fairly limited, and that it is entirely possible to use biofeedback to learn to fool them. A good point, although sufficiently exotic measurement methods might of course require acquiring equally exotic training equipment - getting a galvainc skin response meter is easy, but a fMRI system is not (for the foreseeable future).

Kathleen Taylor held an excellent talk on brain editing. If we assume it will become possible to edit away certain neural networks, like (say) ones causing inappropriate sexual thoughts, what are the ethical and social issues? She quickly went through the usual medical ethical issues (side effects, problems of developing it, long term effectiveness, risks, autonomy, privacy etc) and then got into a very interesting sociological analysis of the different frameworks used to judge interventions. In the medical mental framework the doctor and patient have particular roles, with a strong centering on the needs and desires of the patient. When the patient is not sufficiently autonomous, for example due to mental illness, a mental illness framework is used instead where the doctor is given greater control. But the aim is still to help the patient. On the other hand, when a crime has been committed (the criminal is assumed to rationally chose to do what he does), we use a criminality framework where the rights of the criminal become radically circumscribed due to his moral culpability. But in cases of deviancy such as pedophilia the criminal framework is mixed with the mental illness framework. Due to various social psychological processes such as essentialisation (a trait of a person, like pedophilia, is seen as the core of that person rather than just one property among others) and stereotyping the person practically loses all rights - both freedom and the right not to have his mind modfied. Deviants have no rights, they are not part of our "universe of obligations" psychologically speaking. And since deviancy is to a large degree a socially constructed class (Kathleen stressed that there certainly are real kinds of deviants, but the entire class is very much culturally defined and not a natural kind) this means that governing powers gain tremendous access to forcibly "adjust" these people, and possibly also expand the class if politically expedient. Hence brain editing technology ought to be kept out of the hands of politicians, marketers and the military. Good luck. But I think her analysis is spot on, and a good case of neuroethics actually daring to become neuropolitics.

Neil Levy, in whose honor the seminar was held, described some ongoing research in treating PTSD with propranolol. The idea is to stop the vicious circleof a traumatic, strongly encoded memory being triggered and in turn triggering adrenergic reactions that re-encode it strongly. But Neil argued that if the somatic marker hypothesis holds, the treatment might also affect the moral judgement afterwards of the events (not necessarily for ill). It will be interesting to see what the results are.

Guy Kahane explained in the day's most philosophical talk the ethics of brain reading techniques: do we have any right to mental privacy. His conclusion seems to be that most arguments for mental privacy fail, but there is a Kantian argument about the difference between our mental and behavioral worlds that holds ethical water. We can decide whether to act or not, but we cannot decide not to think. Hence the "deliberative backstage" of our minds is different from our external actions, and need particular protection.

Morten Kringelbach talked on pleasure, desire and deep brain stimulation. After a very good historical overview that seemed to show that pleasure is creeping ever more frontally the more it is researched he presented the modern models (a la Edmund Rolls). The most interesting aspect if of course the mounting evidence that desire and pleasure are possibly separable - there might be developed stimulations that give pleasure without desire. Let's hope it is possible.

Finally Susan Hurley talked about her shared circuit model of cognition. Her take on neuroethics was as an explanation of how subpersonal systems enable an ethical life. The circuit model is a nice account of increasing levels of sophisticated modelling of the outside world, from homeostasis over predictove simulation to mirroring, simulative mirroring and eventually the internal generation of counterfactual input (see her papers for detail). It all seemed to fit in nicely with the account given by Peter Gärdenfors in How Homo Became Sapiens and Kohlberg's moral stages.

Very stimulating, especially since it was obvious this is a field in exciting rapid development. As soon as it will gets more well defined it will become stable and boring. By then I expect we will hopefully be on the barricades (or at the conference centers) hashing out tomorrow's neuropolitics.