December 31, 2006

Getting Both Privacy and Functionality

(This relates to my report Den hänsynsfulla taggen, see also this brief english summary)

I came across A Platform for RFID Security and Privacy Administration by Melanie R. Rieback, Georgi N. Gaydadjiev, Bruno Crispo, Rutger F.H. Hofman & Andrew S. Tanenbaum. It is an interesting description of the "RFID Guardian", essentially a wearable RFID firewall that enables access control and privacy for RFID tags in one's vicinity.

I came across A Platform for RFID Security and Privacy Administration by Melanie R. Rieback, Georgi N. Gaydadjiev, Bruno Crispo, Rutger F.H. Hofman & Andrew S. Tanenbaum. It is an interesting description of the "RFID Guardian", essentially a wearable RFID firewall that enables access control and privacy for RFID tags in one's vicinity.

The idea is that the device intercepts requests and can then jam them or let them through, enabling access control. It also logs what is going on, enabling the user to find out when and what requests arrive and whether unknown tags have appeared. Since it is a pretty smart device it can be context aware and, I guess, linked to other wearable devices.

Overall this is a very nice solution for privacy. Blocker tags require every tag to follow particular standards, putting tags into faraday cages is cumbersome and limits their uses, as does burning them out. Also, this enables positive control over one's "tag cloud", something which is very important for making it trustworthy. Privacy is not just about not delivering unintended information to other parties, it is also about knowing when somebody snoops - or just the pattern of information flows. If the price of privacy is lack of functionality we will likely end up ditching it for the cool and useful new functions. But we can get both.

Of course, the current design is pretty complex. Setting ACLs isn't trivial, and what does a particular pattern actually mean? To make this kind of device useful it needs 1) a simple user interface and 2) to be integrated in our normal electronics. It seems plausible that this is yet another thing to add to the cellphone. RFID-cellphones already exist and the Japanese are looking into commercial applications. Adding the privacy functionality is technically likely not too demanding. The real challenge is going to be to get people to buy it. Just like computer firewalls it has taken quite a bit of bad experiences with low default security for people to realize the need (or vendors to add security as a default).

Another interesting issue is handling multiple systems. If I block access to all my unknown tags in my vicinity, how much will I be distrupting my neighbour's identity infrastructure? It seems that having people use these systems will not just stimulate setting ownership but also developing of social norms about who gets to jam what identity signals when and where. Indiscriminate jamming is just as destructive as indiscriminate transparency.

While googling up the link for the paper I also found this nice bibliography of security and privacy in RFID systems. Lots of more yummy things to read and consider.

December 27, 2006

A Long and Happy Life

During my talk in second life I claimed that if long lives produced ennui, we ought to see that in our happiness statistics. Here is a look at the link between current life expectancy and happiness.

Nationmaster is an excellent tool to play with, although I find some of its plots somewhat useless (I want more control over them). NationMaster - Scatterplot: Lifestyle > Happiness net vs Lifestyle > Life satisfaction for example messes things up seriously, despite the cheerful claim that it is all significant.

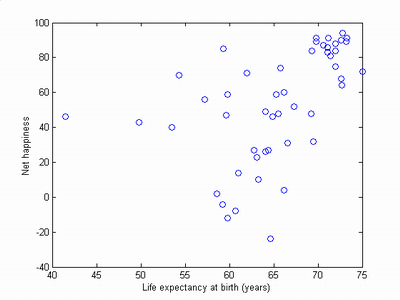

Taking the happiness and life expectancy numbers and plotting them together we get this:

The correlation is 0.488 ± 0.0140 (where I used jackknifing to get the standard deviation estimate). The biggest outlier is Nigeria which is surprisingly happy despite everything, a bit like Bangladesh, Ghana and India on the same horisontal 'short-lived but happy' branch. The lower 'sad-but-reasonably-long-lived' branch is Eastern europe with Bulgaria as the most extreme case. But in general the correlation is pretty clear: the longer you live, the happier you tend to be. The most long-lived countries are also happiest.

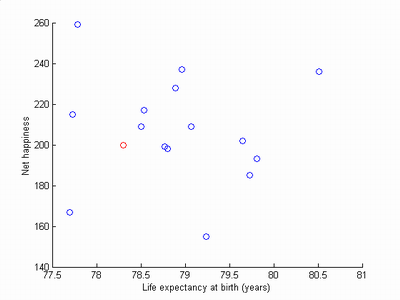

But maybe we are seeing a confound due to the disparities in wealth and health here? If we take the Eurobarometer data instead and look at EU countries (all generally wealthy and healthy), we get this scatter:

The red circle is EU averages. The happiness value here is calculated as summing the not at all satisfied weighted by 0, the not very satisfied by 1, fairly satisfied by 2 and the very satisfied by 3; a measure adding the two most positive classes and subtracting the most negative as in the first diagram does not change anything qualitatively.

We actually get a negative correlation now, -0.0679 ± 0.1009, but as the standard deviation shows this is not significantly different from no correlation.

Denmark is perhaps a bit of an outlier in terms of being very satisfied but not living long compared to neighbours. See Why Danes are smug: comparative study of life satisfaction in the European Union (Christensen et al., BMJ 2006;333:1289-1291 23 December) for a deeper analysis. Myself, I blame the smørrebrød. We Swedes are of course both long-lived and happy (despite the extreme level of sick leave).

So the data supports my claim that at least given current life expectancies there is no sign that people live long lives of ennui.

I have not yet analysed historical data, since that would be an even better way of testing whether rising life expectancies are linked to declining levels of happiness. Given that plots of life satisfaction generally remain fairly stable in most EU countries while life expectancy increases linearly with time, it seems unlikely that there is any correlation hidden there. The real test would be to look at countries that have experienced major gains in life expectancy over the last century, but happiness data are hard to find. We need to investigate some good proxy to see if there has been a major change in lifespan-related happiness.

Further, we should look at life satisfaction as a function of age. A quick look into the World Values Survey does not show a strong difference between the happiness of young, middle aged and old. Comparing different countries I got the impression that in richer countries people moved towards "very happy" as they aged while in less rich countries people moved away. A longitudinal study shows that life satisfaction peaks around 65, but is highly individual as personality factors and health play a big role. Poor health, loneliness and economical problems appear to be major predictors for less satisfaction in old age, and since presumably these problems are easier to fix in affluent societies that may contribute the change. But we could of course get complex confounders here due to different family patterns in different countries.

So far longer healthier lives do not look like they promote ennui. Maybe a radically longer life could do it, but given that we so far have not had any actual experience of it the predictions of pro-death writers are just conjecture more based on ennui during short lives. The causes of that boredom (clinical depression, lack of imagination, illness etc) are likely entirely unrelated to the length of life and can be combatted by culturing zest for life. As Nietzsche said during a time where the life expectancy in western Europe was around 37 years, "Isn't life a hundred times too short to get bored with it?"

December 20, 2006

He who has hope has health

Today's CNE health blog was about how optimism promotes health.

Rageing Against Ageing

This monday I held a talk for the first time in Second Life, at the Uvvy Island conference center. The subject was the scientific, ethical and economical case for life extension, as well as some of my thoughts on how to create a life-affirming "culture of longevity". Eugene Leitl helpfully posted the transcript of my talk and surrounding chat.

This monday I held a talk for the first time in Second Life, at the Uvvy Island conference center. The subject was the scientific, ethical and economical case for life extension, as well as some of my thoughts on how to create a life-affirming "culture of longevity". Eugene Leitl helpfully posted the transcript of my talk and surrounding chat.

It was an interesting experience lecturing in SL. I have relatively little experience with the system, but it has some promise. I think scripting gestures as part of cut-and-pasting a prewritten talk might be very useful, although I found it relevant to also direct the avatar's gaze by the mouse. The hardest part was keeping up with the general discussion. Chats tend to be messy since everybody are essentially talking at the same time. We might need some tools for organising this, for example by threading chats. Some of the questions were the typical "but what about overpopulation?" doubts, others quite high-level and intriguing. It seems that chat is not the best mode for actually thinking deeply, but might be a good way of voicing concerns that can later be analysed at more length on mailing lists or in updated versions of the paper. Overall, a stimulating experience although I think I'm a better lecturer in real life rather than second life.

Thanks to Giulio Prisco for the photo.

December 19, 2006

Oliver Sachs in space with vampires

Oliver Sachs in space with vampires. I think that sums up Peter Watts’ Blindsight: it combines hard space sf with cognitive neuroscience and a bit of horror. Practically every intriguing brain syndrome is there, from the Asperger protagonist over hallucinations of unseen presences to those conditions we neuroscientists use to harass philosophers with, like patients being fully convinced they are dead or blind people not noticing they are blind.

Oliver Sachs in space with vampires. I think that sums up Peter Watts’ Blindsight: it combines hard space sf with cognitive neuroscience and a bit of horror. Practically every intriguing brain syndrome is there, from the Asperger protagonist over hallucinations of unseen presences to those conditions we neuroscientists use to harass philosophers with, like patients being fully convinced they are dead or blind people not noticing they are blind.

The basic story is a first contact story. After a strange survey of Earth aliens have been detected in the Oort cloud, and a spaceship manned with a small crew of highly enhanced humans are sent to initiate contact. The Theseus has many similarities with the Discovery in 2001, a happy case of convergent evolution of technological extrapolation. As a first contact story it is well done – the slow build-up to meeting the very alien aliens works great. Sizeable amounts of evolution and neuroscience creep in without being too expository, although this is still very much a cerebral book rather than roaring adventure and deep characterization. And the basic threat/dilemma the crew of the Theseus discover is quite profound.

The enhancements of the crew are plausibly problematic. The synesthetic biologist extends his senses and motor abilities through different sensors and actuators, but at the price of being at a disadvantage in sensing and moving his own body. Another biologist with the same enhancements has practically no body language and consistently uses ‘it’ instead of gendered pronouns. The linguist has multiple personalities, but instead of being regarded as a disorder it is now regarded as a useful and desirable state that can be supported and improved into true multitasking and multimindedness. Perhaps the most outrageous and original enhancement is the vampire captain of the ship. Vampirism is both a past evolutionary failure, an anthropophagic offshoot of our species that died out due to its vulnerability to right angles, and a successful form of posthuman existence thanks to modern biotechnology. Except of course that some of the quirks like sociopathy and scaring humans are intrinsically linked with the superior traits. There is a hilarious presentation online giving some of the background, well worth experiencing.

The Aspergers protagonist appears almost normal – except in the flashbacks to his failed relationship with a woman, where the utter strangeness and tragedy of his highly developed ability to simulate empathy become startlingly clear.

Comparing with Disch’s deservedly famous Camp Concentration I happened to read a few days earlier, I think Watts does a good job. Watts turns the situation inside out: it is not the value and high costs of these enhancements that form a Faustian bargain, but the normal state of Homo sapiens may be the Faustian thing.

The novel reads like a Greg Egan novel. The Aspergeresque theme of looking in at humanity from the chilly world of rational outsiderdom seems to recur. It is also crammed with the kind of big scale evolutionary and sociological speculation Karl Schroeder has been doing. It is no surprise the author admits Blindsight is a kind of response to Schroeder’s Permanence.

What I love about the novel is that it gets its facts so right about tiny things. Parker spirals, maternal response opioids, Sanduloviciu plasmas, taking dimenhydrinate before going to a spacewalk – the list is long. The appendices are highly readable and come with full literature citations. If Disch played with exotic alchemical, art history and theological allusions Watts plays with allusions to state-of-the-art science (and since science aims for clarity giving references is much more fitting). The Chernoff faces mentioned is probably the first vampiric information design application that anybody has ever invented.

Spoilers and discussion below

The basic claim is that consciousness is useless. Intelligence may be highly adaptable, but having a subjective experience and thinking so much about oneself (Watts seems to conflate the two kinds of experiences) may actually be negative. It takes resources, it slows us down, it misdirects energy to various endeavours that do not contribute to our evolutionary fitness.

The vampires accidentally evolved a tendency to have deadly seizures when seeing right angles, a trait that was completely neutral in the right-angle free natural environment. Since the population was small and the tendency was linked to adaptive cognitive abilities this mutation became fixed, in the end dooming the species when humans discovered the fatal weakness. In the same way Watts seems to suggest we might have fixed another useless trait – consciousness – linked to our useful mental capacities. This, just like the vampires’ flaw, was completely random and unique. Most other intelligent species evolve without developing consciousness.

I think Watts asks the important question “what use is consciousness?” but I think he gets into trouble because his conflation of self-awareness and qualia. To my knowledge there is nothing useful about qualia at all, except to give an excuse for philosophers of mind to get good salaries. On the other hand, we are surprisingly attached to them – we want to experience the world, and experience the experiencing – but I don’t know how much this is really valuing the qualia for themselves or mixing them up with general survival and cognition. When thinking of a life without qualia most of us mix it up with being dead (and the zombie terminology used in the normal discussions don’t help), and since we find being dead undesirable we think being without qualia would be undesirable. But that doesn’t tell us much about their real value to us.

My own position is that qualia are simply how information feels when it is processed, and it is not possible to avoid them!

Being aware of a self is on the other hand clearly useful in many situations. It is not just that the information about a self model is helpful in directing behaviour, it is that experience about one’s past reactions and behaviour is useful for predicting what will happen in future interactions with the environment. In social creatures other-models would easily generalise to self-models, especially when second- and third-order thinking about who knows what and how they will react to this becomes important.

Self-awareness is probably less fundamental than qualia, since we know it can be lost (in states of flow, deep meditation) or distorted. Creatures like the Scramblers in the novel might also lack self-awareness since the borders of their minds are very fuzzy. It is never clear in the novel to what extent they form a group intelligence. The border between being a being in a group and being the group might be heavily blurred as communication abilities increase.

In the end I think Watts’ case is intriguing, but I’m not convinced. However, I do think we have a very parochial view of how intelligence should work. All vertebrates have nearly the same large-scale brain topology, and the differences between mammals are even smaller (all the pieces and wiring are there, it just looks like some have more neurons in some systems and localized adaptations). This may give us a very anthropocentric view of what it means to be a being in terms of having a motivational system, emotions, decision making along certain lines, self-awareness and social interactions. I do not think intelligence has to be combined with decision-making in our sense (one could imagine something akin to a super-Google), selfhood could be heavily blurred or shared, subjective risk/reward could run on entirely different schemes and decisions could be based on something else than a modified motor planning system.

December 15, 2006

The Anti-Trial Directive

This week on CNE I wrote about the clinical trials directive, an EU directive with proven disastrous effects. I have previously written about it, but it deserves to be flogged again.

This week on CNE I wrote about the clinical trials directive, an EU directive with proven disastrous effects. I have previously written about it, but it deserves to be flogged again.

It manages to double costs of research trials, produce an endless number of false alarms and reduces the number of trials held. Especially international trials are now harder since previously the rules were incompatible, requiring much legal footwork, but now the interpretation of the directive are different and uncertain - and much harder to find out, since no regulatory agency will ever admit that it is not following all EU regulations perfectly and as intended. The result is risk aversion and over-interpretation of the rules since nobody dares being wrong about them.

It is a typical case of the all too common administrative assumption that extra rules have no costs and simplify things.

December 12, 2006

No Policing the Social Aspects of Life

As a swede, I'm constantly amazed how many sane drug policy ideas are proposed in Britain. Now the sports minister Richard Caborn questions the ban on 'social drugs' in sport. He suggested that the key anti-doping issue in sport was whether drugs enhance performance or not, and that the drug authority Wada should not be policing the "social aspects of life".

As a swede, I'm constantly amazed how many sane drug policy ideas are proposed in Britain. Now the sports minister Richard Caborn questions the ban on 'social drugs' in sport. He suggested that the key anti-doping issue in sport was whether drugs enhance performance or not, and that the drug authority Wada should not be policing the "social aspects of life".

Being in general in favor of allowing people to enhance themselves, I can nevertheless agree that for sports fairness purposes the participants should agree to not enhance (or all enhance). But it is strange that the views in such a circumscribed and frankly odd area of society should be used to set policy in general about enhancing drugs. If I, fully informed of the risks, want to take steroids to build up my muscle mass for aesthetic purposes I cannot legally do this (and cannot get medical oversight to monitor my health) since all non-treatment use of steroids is banned as doping (at least in Sweden). It seems to me that the rational thing to do is to leave sports to set up its own rules, based on internal contracts rather than state law.

The most rational defense of anti-doping policies is to maintain the health of athletes. But elite athletes are already subjecting themselves to training that erodes their health even when fully legal. Hence it would make more sense to make health monitoring mandatory and keep people from participating if they would have a high likeliehood of being seriously injured, regardless of the cause of the problem.

The claim that athletes have a duty to be clean since they are idols to many seems very weak. Why not place the same legal demands on other celebrities, politicians or anybody successful? The bodies of athletes seem to have become a public property that has no rights to medical privacy and is controlled to a significant degree by outside rules, with every behavior under public scrutiny. I doubt we would accept that in any other profession, and it doesn't seem very moral in its current state. At the same time the ideals athletes are supposed to achieve are extreme; I get the impression that the ideal athlete is some kind of cartoonish warrior-monk. Yet people seem to want to see humans compete.

I think Mr Caborn was right when he said anti-doping agencies have no right to get into the social aspects of life, not even of athletes. Outside agencies only have a right to involve themselves in aspects of our lives that directly relate to their domain, such as through contract law or recognized social agreement. While it might be theoretically possible that society might agree that athletes have limited rights of privacy and that the general interest of sports overrules other human rights, I find it unlikely.

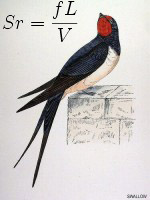

Easy to Swallow

style.org > Estimating the Airspeed Velocity of an Unladen Swallow is a beautiful and fun analysis of this classic question, not even leaving out the problem of which African swallow we are talking about. The graphs are even better in the preceeding page on Strouhal numbers. The site itself is also worth examining for its nice infographics.

style.org > Estimating the Airspeed Velocity of an Unladen Swallow is a beautiful and fun analysis of this classic question, not even leaving out the problem of which African swallow we are talking about. The graphs are even better in the preceeding page on Strouhal numbers. The site itself is also worth examining for its nice infographics.

One fun implication of this is that birds on a low gravity world like a fictional terraformed Mars fly at the same speed, but animals tend to run slower. Cats clearly need to be just as stealthy as on Earth.

I found the site from the discussions on Edward Tufte's site, of course. Another interesting discussion involves information and information graphics in the patient-doctor relation. That also linked to the Ping project, an open source project for patient-owned medical records, and a paper about visualizing medical risk with roulette wheels and dartboards. That there was a discussion of information markets was a bit of a surprise, although Robin's entry into it was less of a surprise :-) That discussion brings up one problem I have with them: being a highly visual thinker I'd really like to have good visualisation methods of the information markets to actually get a good intuition about them.

December 11, 2006

We Must Act Now to Silence, Not Think!

According to Germany plans crackdown on violent online games - Financial Times - MSNBC.com the regional governments of Bavaria and Lower Saxony have drafted a bill that would subject developers, distributors and players of video games whose goal is to inflict "cruel violence on humans or human-looking characters" to a fine and a maximum of one year in jail.

According to Germany plans crackdown on violent online games - Financial Times - MSNBC.com the regional governments of Bavaria and Lower Saxony have drafted a bill that would subject developers, distributors and players of video games whose goal is to inflict "cruel violence on humans or human-looking characters" to a fine and a maximum of one year in jail.

It is the typical overreaction to a tragic school shooting. Since the real causes are probably diffuse, individual and hard to deal with a suitable scapegoat that can at least in principle be dealt with has to be found. It is also somewhat consistent with the famous

What makes me curious is the ethical implications. Suppose it was not computer games but violent, sadistic books? Suddenly the bill would likely be seen as utterly draconic and unconstitutional. Germany has strong protections of freedom of speech, and although there are some constraints that in principle could prevent such a book it is very likely that it would be deemed falling under freedom of art and press. It is easy to attack computer games since they do not represent mainstream high culture, and many opponents do not even recognize them as culture or social expression (Eudoxa has a very good report by Rasmus Fleischer (in Swedish) criticising this).

This moves the issue close to my own area, bioethics of enhancement. A very common kind of objection to enhancing humans is that even if a particular kind of enhancement does not directly hurt human dignity it will lead to a society moving towards disregard of human dignity, filled with instrumentalisation of human lives and inequality, hence enhancement should be resisted. Now, if we accept this argument as valid for the moment (there is a lot of technological determinism, wooly slippery slope thinking and lack of empirical support here that I usually attack) it implies that the consequences are bad enough to merit not just not supporting relevant research but limiting people's freedom to do it, possibly even making it illegal (George Annas is perhaps the most extreme, arguing that it should be made a crime against humanity).

Here it is the outcome that is regarded as the problem, so the argument is consequentialist (although a lot of the people making it actually seem to be more perturbed by the nonconsequentialist aspects of enhancement). Hence any other activity that were equally or more likely to cause this bad future society must be resisted equally strongly. That includes computer games and books. It is entirely legal in all western countries to write a book laying out a philosophical and aesthetic case for why it would be good to reduce all humans to resources to be used by the Powers That Be and why human dignity and equality are irrelevant (in Germany and some other countries this mustn't be argued from a nazi standpoint of course, but doing it from any other is allowed). If freedom of research and action must be curtailed to prevent threats to human dignity, then clearly freedom of speech must be equally curtailed.

These curtailments have one very worrying aspect: they happen before the fact. They are based on the assumed potential for information or technology to cause bad effects, but preclude any testing of whether they actually have them. Hence the rules will be founded on ignorance.

On the other hand, setting rules after bad experiences is rationally possible only when these experiences actually can be traced to the non-curtailed activities. Has the existence and publication of de Sade's The 120 Days of Sodom made mankind worse? It is impossible to give a clear answer since its effects have percolated so widely and spawned responses in all directions and of all kinds. Yes, the book is boring and vile, yet its overall impact in terms of reactions in psychoanalysis, freedom of press, existentialism and whatnot is far more complex and hard to evaluate. Would we be better of if it had been burned? It is very convenient to blame books (or computer games) for the ills of society, especially if they are burned and future generations cannot check the likeliehood of these claims.

Overall the aim of this kind of culture-protecting curtailments of freedom is to protect society from a cultural change that is (regarded by some sufficiently influential group) as negative. It is somewhat paradoxal: in order to safeguard human dignity human freedom has to be reduced (but doesn't dignity require freedom to express itself?). Worse, this activity is exactly the kind of subjecting the individual to the goals of the Powers That Be that I mentioned in the context of the fictional book. It puts the good of Culture and Society above the good of the people that make them up. And once you start to put the abstractions before the people (since they don't know what is best for them, and this is why you can safely disregard their uninformed complaints) there are so many more things you can make better by ignoring their will!

While the impacts of complex things like books and computer games are hard to estimate, we have quite a bit of data to base our decisions on in regards to reducing freedom of expression. Putting people in jail for producing unwanted expression and preventing its spread has not just been a hallmark of tyrranies, it has quite often helped them rise to power. When it is easy to silence critics - be it legally or just by the chilling effects of the laws - criticism and alternative opinions vanish.

I think attempts to ban anything that actually doesn't have demonstrably bad effects should not be countenanced. We already know the bad effects of that. Instead we might want to find out more. Allow enhancement but monitor the psychological impact of their use. Keep an eye on violent computer games and try to figure out how to avoid mentally disturbed people from playing them - or better, find ways to use the games to discover who is in trouble. It is interesting to note that the proposed legislation will likely affect online games - i.e. the ones that have more of a social component - than single-player games an isolated and troubled youth could be playing. Might babies be thrown out with the bathwater?

As Fleischer pointed out computer games are not just isolated gaming but part of a culture and the basis for much online social interaction. That many are violent may be an expression of a desire to master or interact with the most forbidden in our otherwise (historically speaking) peaceful western world, violence itself. The more forbidden it becomes, the more schools and adult culture disapproves on any expression of aggression, the more fascinating it will be. Games could just as well be a way of learning how to handle violence and see its limitations, but that form of learning is unlikely to happen because the outside world wants it.

December 09, 2006

Should Economics be Part of Hard SF?

An interesting set of criticisms of Charles Stross Accelerando, Can the Future Do Without Economic Logic? from Tim Swanson and Isaac Bergman (published by the von Mieses Institute). Essentially the problem is that Stross' economics isn't hard enough.

An interesting set of criticisms of Charles Stross Accelerando, Can the Future Do Without Economic Logic? from Tim Swanson and Isaac Bergman (published by the von Mieses Institute). Essentially the problem is that Stross' economics isn't hard enough.

Compared to most sf Stross gets economy. How many absurd mining planets have we not be subjected to? Time travel business ideas? Interstellar trade is tricky to make realistic and most cyberpunk megacorps would be outcompeted within months. But I think Robin Hanson is right when he thinks that hard sf economy can be done.

Is it just me, or are the demands of hard sf rising? Once you just had to get the physics right, you could assume nearly any weird biology. Gradually sf authors have begun to build ecologies more conscientously and make sure their aliens could have evolved. These days software is slowly getting more plausible. And maybe hard sf is starting to integrate more real economics too. Maybe a true hard sf author in 2020 will have to master not just physics, biology, computer science, economics, sociology, psychology - and write well, of course. We better invent brain enhancements quickly if we are to get anybody with that kind of expertise.

Is a Hypereconomy Stable?

I'm not entirely convinced by the claim that a superintelligent free market would approach the evenly rotating economy and hence become stabler over time.

First, in Stross story Economics 2.0 was not a free market economy, so the objection is invalid.

But even a free market economy might get sufficient bumps by the rapid growth of the posthuman intelligences inside it. Plateaus and breakthroughs in developing whatever software the entities desire/are would introduce noise, and it seems to me that it is not clear at all that a rapidly smarter population (with possibly exponentially growing differences in smartness) would be evenly rotating. Misallocations and adjustments can still occur if they are impossible for intelligences of level X to foresee but obvious for level X+1 (or X+100) intelligences.

I don't think anybody has applied Austrian school economics to distributed societies like Alexander Chislenko's functional soup. If identity is not stable and desires and goals generated from each other and economic demands, how does the economic cycles behave?

Reputation Markets

The critique of the reputation markets seems to be constructive. I guess what we really want is a measure that tells us important things about an entity like trustworthiness, integrity or influence. It really seems to be not just a vectorial variable but better regarded as a tagged one - a reputation as fun might be essential for a comedian and mis-applied to a company. It is not a unitary scalar thing that can be used as money (at least not easily). In different situations different aspects become relevant and can be used in different ways - scientific integrity and expertise ought to be used to judge the epistemic importance of scientific claims in public debate and publication decisions in peer review, but they are rather pointless in a business deal.

We want some way of automatically calculating reputation scores that aggregates the knowledge of many people, and that suggests a market, but it could just as well be something else. If reputations are regarded as more multifaceted than just a single good/bad reputation there would be more parallel and weakly connected markets, which likely would reduce their predictive power. Maybe this is actually an argument for why we need to have low-dimensional reputation scores: they are more stable and calculable than detailled reputations. On the other hand reputations based on agent software doing text/video mining of comments and events might actually calculate new reputation scores on the fly ("Agent, what is his integrity as a green-christian-antifeminist? Is it higher than his trustworthyness as a liberal eugenicist?") And this could be stabilized by getting publicly stated reputation estimates from other individuals, weighing them together by pageRank of social networks.

To me it suggests that reputation markets and other forms of aggregation might be a very good area to study both from an economic perspective and as cognitive enhancement. As stated in the Manifesto for the Reputation Society reputations are a way of dealing with information overload. There might also be public goods problems associated with getting people to formulate reputations and situations where reputations reduce market efficiency, another reason to get economists involved.

December 07, 2006

Defending against Xenoviruses and Endocorruption

Today's CNE Health blog is about xenoviral defense - not defending against the Andromeda strain, but against potential animal retroviruses evolving in xenotransplants. Martine Rothblatt had a very interesting proposal for a global xenodefence that might be even more important in terms of dealing with emerging diseases.

Today's CNE Health blog is about xenoviral defense - not defending against the Andromeda strain, but against potential animal retroviruses evolving in xenotransplants. Martine Rothblatt had a very interesting proposal for a global xenodefence that might be even more important in terms of dealing with emerging diseases.

Last week it the blog about transparency and the evidence-based medicine organisations. (I also noticed that the always interesting Samizdata linked to it).

If there is one thing I think we can get sane and freedom-minded people across the political spectrum united about it is demanding more government transparency. Even if you are a total state-hugger it makes sense to ensure that it is working at optimum efficiency and that it demonstrates its integrity to the unbelievers at every turn. And if you think like me that the evidence is rather firm that governments tend to fall prey to all sorts of public choice pathologies it is even more necessary.

If something is based on taxed money the least we can demand as taxpayers to have as full access to its inner workings as possible. After all, these working are supposed to represent us and be in our interest, so what is there to hide? Any opaqueness must be carefully motivated, not just assumed to be the default state.

Maybe a start would be to demand that the EU allows an independent audit?

Extra, Extra, Read All About it: Not A Number Reinvented!

BBC - Berkshire - Features - 1200-year-old problem 'easy' and SvD: 1200-årigt problem

BBC - Berkshire - Features - 1200-year-old problem 'easy' and SvD: 1200-årigt problem

kan vara löst demonstrate one thing: journalists don't know anything about math. And they rather copy each other than ask an expert if a story is real.

The real story is that a researcher at University of Reading apparently has reinvented Not A Number to 'solve' the problem of division by zero. And he has managed to teach a class of schoolchildren about it.

Let's ignore that NaN has been around for many years, that we know 1/z has a real singularity at zero, that the extended complex plane together with the the Riemann sphere also neatly fixes the problem as does the extended real number line and wheel theory.

But even the quote from Dr Anderson makes me wonder: "Imagine you're landing on an aeroplane and the automatic pilot's working," he suggests. "If it divides by zero and the computer stops working - you're in big trouble. If your heart pacemaker divides by zero, you're dead."

Ever heard of interrupts? Fault tolerant computing? The IEEE 754r standard? After all, he is said to be from the computer science department.

So now I'm eagerly awaiting the truth: who has been pranking or misunderstanding whom here?

Rank Appeal

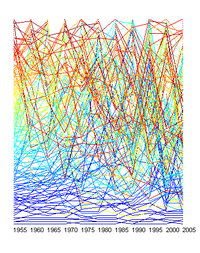

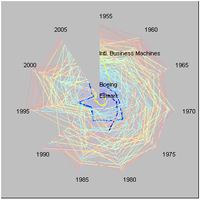

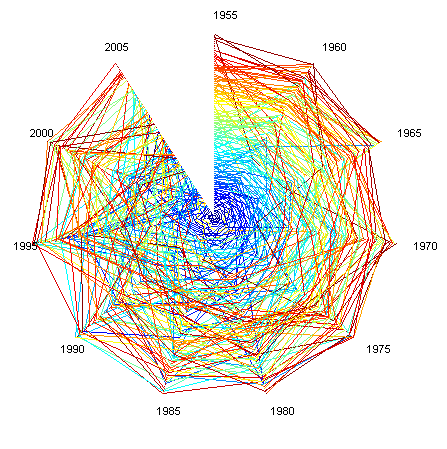

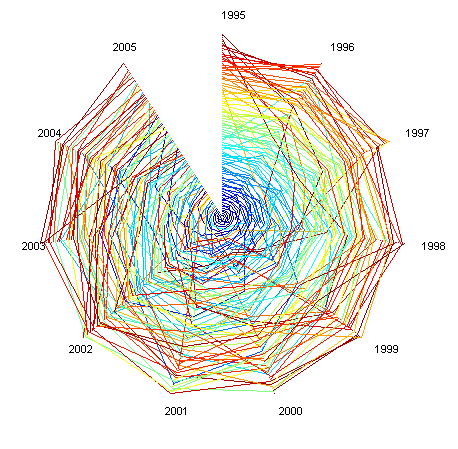

Rank clocks were introduced recently in Michael Batty, Rank clocks Nature 444, 592-596 (30 November 2006). Essentially they are a polar plot of the rank distribution of data over time, enabling the viewer to see how it has changed.

Rank clocks were introduced recently in Michael Batty, Rank clocks Nature 444, 592-596 (30 November 2006). Essentially they are a polar plot of the rank distribution of data over time, enabling the viewer to see how it has changed.

The point of the paper is to show that despite the prevalence of beautiful power laws that stay invariant over time there is actually a lot going on. There is quite a bit of movement going on, and staying in the top positions may be a very temporary thing. Individuals rise and fall, and this is incompatible with the quite common assumption these power laws are due to a 'the rich get richer' process. Batty demonstrates this with the example of city sizes in the US, UK and the world.

So far so good. It is just that I'm annoyed by the rank clock! This seems to be a graphical gimmick rather than a good visualization. First, there is no obvious benefit from a polar plot compared to a rectangular plot - sure, naive readers might more easily understand a clock than a straight diagram, but if they have that problem they will have a hard time understanding rank too. And the polar plot makes it much harder to see if something is rising or falling in ranks - in both cases you get spirals, but the derivative is now represented more by the direction of curvature than the actual direction! Placing the first ranked at the center serves to deemphasize them and their changes while emphasizes what happens at the rim. The usage of bright saturated colors is of course endemic to all science, but using heavily overlapping lines really doesn't help either.

The Fortunes of the 500

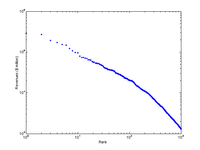

Anyway, I couldn't resist playing around with rank data myself. So I took the Fortune 500 companies as raw material. Looking at the assets as a function of rank produces a very nice power law (or perhaps better, two power laws).

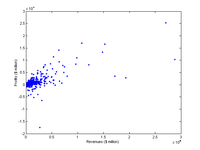

Incidentally, plotting assets vs profits showed that there is a general correlation between size and profit and that the biggest ones seldom show losses.

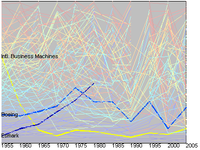

Plotting the 100 biggest companies for the period 1955-2005 (five year steps) and 1995-2005 (one year steps) produce the following rank clocks (color depends on the rank a company first appeared at):

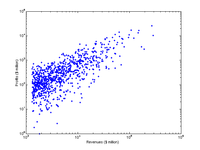

The important thing is that the volatility is lowest among the biggest ones. Is this clear in the picture? Now compare this with a simple rectangular plot:

Suddenly it is much easier to see, despite the color scheme. Muting the color scheme and thickening lines to bring out a few interesting companies is even better:

If there is one thing to learn from this dataset it is that even in a situation where "the rich get richer" is a plausible dynamics it is still turbulent around the top of the power law. The truly big are relatively slow changing, but sometimes new giants just jump in - Wal-Mart has been on the list only since 94. Of the 10 biggest in 1955 only four are left today.

Of course it is conceptually wrong to put the biggest companies at the bottom like I have done here. Biggest should be on top.

I based the color ordering on at what rank a company appears for the first time. This has a nice side effect in that it allows to see the mixing going on: a red company in the top arrived small and grew, while a blue company in the messy lower rankings has fallen from an initial position. But likely the color scheme should be calmer and more 1D.

The Matlab code I used to make the plots can be found here: Download file

December 04, 2006

Dungeons & Discourse

Here is a great comic, at least if you like roleplaying games and philosophy: Dresden Codak casts Magic Missile.

Here is a great comic, at least if you like roleplaying games and philosophy: Dresden Codak casts Magic Missile.

Overall Dresden Codak is one of the better webcomics in terms of quality, weird content and design. The boustrophedonic layout is confusing at first, but works as soon as you figure it out.

While still on the subject of webcomics worth examining, Dr McNinja is another excellent comic that manages to reach great levels of action weirdness ("Well, if I may whip up an ectoplasmic slide projection?"). Gunnerkrigg Court is more poetic and gently humorous. In that neighbourhood I would also place Minus. In the category "best/worst use of scrolling" Nine Planets Without Intelligent Life is a good contender. Finally, Irregular Webcomic demonstrates the power of Lego.

In the Borderlands of Epistemology, Economics and Psychology

I'm (hopefully) contributing to the blog Overcoming Bias. It is a nice academic blog dealing with the issue of biases that deflect us from truth.

December 03, 2006

Embracing Enhancment

Here is a paper Nick and I wrote: Cognitive Enhancement: Methods, Ethics, Regulatory Challenges (for the proceedings on the Forbidding Science? coference at Arizona State University's College Law Center for the Study of Law, Science & Technology, January 12 and 13, 2006)

Here is a paper Nick and I wrote: Cognitive Enhancement: Methods, Ethics, Regulatory Challenges (for the proceedings on the Forbidding Science? coference at Arizona State University's College Law Center for the Study of Law, Science & Technology, January 12 and 13, 2006)

It is an overview of cognitive enhancement methods, some ethical issues (obviously this can be extended to a book length treatment) and some discussion of how to regulate things.

Our main conclusion is that regulation might be needed to ensure the development of cognitive enhancement rather than limit it. The social benefits appear to be pretty solid and we are already doing our best to safeguard and improve cognition in a myriad other ways (be it reducing lead in drinking water, compulsory education or attempts to ensure sound decisionmaking). So society might need to consider how to change drug development and licencing to promote safe and cheap cognition enhancement drugs. Similarly setting acceptable baselines for risk in enhancement might be beneficial, rather than just assuming it all evil "non-medicine". A real cultural challenge is destigmatizing the use of enhancers: creating positive norms for responsible use (and when it is appopriate to enhance) goes a long way and will in turn help setting up the harder forms of regulation.

December 02, 2006

Great rather by design than by achievement

Renaissance is a true cyberpunk movie - great style, no substance.

Renaissance is a true cyberpunk movie - great style, no substance.

The closest comparision I can make is Ghost in the Shell, but where the manga/animes/films started out in the cyberpunk world they matured beyond it. The issues the anime deals with a far more posthuman and complex than what Renaissance allows itself to tackle. GitS successfully burned the motherhood statement while Renaissance stayed within the comfortable lines of noir and cyberpunk.

The sheer elegance of the the postprocessed Paris is breathtaking, including details such as the transparent walkways and the phone/wearables. In fact, the people looked the most artificial, almost like Poser characters. As always it is the quick sharp movements that make people look real. In many places they used particle systems to model smoke, fire and water with embarrassingly bad results - but when real water shows up it is a beauty.

In the end this movie will be remembered for its style, not for its plot. But it always annoys me that filmmakers have such a stupid concept of how research is done. If you know that two researchers working on the same research area have stumbled on the same great secret you don't need them to rediscover it - it just speeds things up a lot, but merely the information that this is where the secret is is often enough (compare to the Soviet hydrogen bomb). If you are an evil megacorporation that doesn't trust anybody you store backups of what your scientists are doing. I think the mistake here is the cultural assumption that science is magic. A kind of hermetic magic based on secrets that cannot be decyphered, only taught by masters to their students. That it actually is a big, open bazaar of concepts and practices doesn't fit in. The real problem isn't to keep your great idea secret but to get anybody to listen to it.

The Renaissance of the fifteenth century was, in many things, great rather by what it designed that by what it achieved.

Walter PaterPosted by Anders3 at 03:20 AM | Comments (0)