July 24, 2008

Yaaay! We're doomed!

For the last week or so I have been involved with workshops and a conference about Global Catastrophic Risks - disasters that threaten a sizeable fraction of humanity or the survival of the human species itself. Some might go even further like wiping out the biosphere or the universe, but we mainly kept this anthropocentric.

For the last week or so I have been involved with workshops and a conference about Global Catastrophic Risks - disasters that threaten a sizeable fraction of humanity or the survival of the human species itself. Some might go even further like wiping out the biosphere or the universe, but we mainly kept this anthropocentric.

To sum up a lot of talks and discussion by lots of smart people:

In the past threats were from nature, now they are human-made. The good news is that we have reduced overall risk, but that might just have pushed up large, unlikely risks. To some extent we are dealing with a luxury problem: when small disasters happen all the time we do not have the time to plan for the big ones. But it could also be a forest fire problem: by reducing small disasters we might set ourselves up for bigger ones. In the case of forest fires preventing small ones lead to a build-up of combustible plants and debris on the forest floor that eventually leads to a major conflagration. In the case of banking systems we might prevent banks from going bust, but that adds to the inefficiencies and distributed risk of the whole system.

The top existential risk concerns seemed to be bioweapons, nanoweapons, superintelligence and "other bangs". Note that these risks are right now low probability, but likely to grow in danger over time. The "other bangs" category corresponds to extinction events that we so far have not thought about. My argument for it is that if the Great Silence (the absence of alien civilizations) is due to disasters, it has to be disasters that are 1) very big, 2) hard to predict even when you know or suspect they are there. Looking at near-term risks nuclear war looks like it is making a comeback due to recent nuclear winter simulations (it is not the nukes that kill, but the famine after failed crops), and a terrorist nuke can ruin everyone's day despite being just a local mess. Global dictatorships should not be discounted either, especially if highly disruptive technologies crop up - or powerful content management systems instituted to deal with disruptive technologies. Astronomical threats on the other hand seem to be receeding (with the possible exceptions of dark comets, Eta Carina having a spherical hypernova or WR 104 sending a gamma ray burst at us). Similarly nobody took physics disasters seriously. Climate change may be messy and increases various risks, but is far "milder" than most discussed disasters. Instead it is a slow problem that suffers more than usual from coordination and uncertainties. Radical climate changes cannot be discounted entirely, but do not seem terribly likely.

Probability matters, but is hard to do right. Practically all debates where people did not agree dealt with probability of some kind. Not only are objective and subjective probabilities hard to distinguish, it matters enormously whether we think of the probability of something happening within a span of 50 years or to the end of time. The risk that a giant meteor will strike is minuscule per year, but pretty certain if we wait long enough (and do not stop them) - but other threats are likely to occur long before mankind is wiped out by a dinosaur killer, so relative, conditional and changing probabilities also matter. Today pandemics and nuclear wars may be a large fraction of the risk probability mass, in a few decades bioweapons and nanoweapons might be much more significant. Worse, even when we estimate probabilities sensibly we have a decent chance of being wrong anyway. Just having people estimate likelihoods on the other hand is to invite cognitive biases, politics and mixing up probability with concern. Simulations and models are often problematic, yet doubting their accuracy does not imply that one should be complacent.

Probability matters, but is hard to do right. Practically all debates where people did not agree dealt with probability of some kind. Not only are objective and subjective probabilities hard to distinguish, it matters enormously whether we think of the probability of something happening within a span of 50 years or to the end of time. The risk that a giant meteor will strike is minuscule per year, but pretty certain if we wait long enough (and do not stop them) - but other threats are likely to occur long before mankind is wiped out by a dinosaur killer, so relative, conditional and changing probabilities also matter. Today pandemics and nuclear wars may be a large fraction of the risk probability mass, in a few decades bioweapons and nanoweapons might be much more significant. Worse, even when we estimate probabilities sensibly we have a decent chance of being wrong anyway. Just having people estimate likelihoods on the other hand is to invite cognitive biases, politics and mixing up probability with concern. Simulations and models are often problematic, yet doubting their accuracy does not imply that one should be complacent.

Fat tails are dangerous. Many disasters have a "fat tail" distribution where the likelihood of very large disasters declines as a power-law of size. This means that the total number of causalities over time is dominated by the largest disaster, not the median disaster. Some disasters like earthquakes probably have a cut-off (they are local, and even a great tsunami is local to a particular ocean and its shores), but wars and democides could potentially go all the way up to the total human population. Governments may be best at managing median disasters, not the extreme ones where no old rules apply - here we need new approaches (decentralization and decoordination? in-depth resiliency?).

Building refuges makes sense, but is fraught with practical and political problems. Having underground redoubts where populations are isolated for long periods of time yet have the right equipment to return after a disaster might increase species survival chances a lot. The problem is that they are going to have visible costs and mostly not do anything visibly useful. Robin Hanson suggested an interesting refuge market that allows people to vote with their wallets, giving good information about the current risks and a way of getting a semirandom sample of people into refuges. There could even be competing refuge organisations. The main problem is the expense of setting up even a small one. Perhaps it is better to ensure that nomadic people in remote corners of the earth remain self-sufficient.

Societal breakdown is bad. Many disasters kill more people through the chaos afterwards than through the disaster itself. A global disaster could kill us by disrupting the fragile global economical system, destroying economies of scale and networks of trust. Many kinds of disasters would also produce societal breakdowns, so this is a kind of common mechanism of doing damage that could be dealt with. If we can increase resiliency to breakdowns or ensure that parts do not break down, disasters can be ameliorated. Right now few people are considering how to do "civilization resiliency", but more should.

Cognitive biases make our risk thinking bad. Most of the time cognitive biases have small stakes, and just cause everyday mistakes. In a disaster small irrationalities can suddenly become deadly. We are under-investing in dealing with uncommon, "silly" or "unthinkable" disasters, we allocate resources based on probability or harm estimates that are biased and we might overreact when something happens.

Cognitive biases make our risk thinking bad. Most of the time cognitive biases have small stakes, and just cause everyday mistakes. In a disaster small irrationalities can suddenly become deadly. We are under-investing in dealing with uncommon, "silly" or "unthinkable" disasters, we allocate resources based on probability or harm estimates that are biased and we might overreact when something happens.

Risks and risk thinking are highly cultural and sociological. Although we may attempt to consider it rationally, most risk thinking in society is not rational at all and influenced by other factors. James Hughes gave a talk about religious millennialism and showed how its different types recur in thinking about disasters or end of the world scenarios even among secular people (as well as religious opinion influencing real risk planning). Steve Rayner described the various sociological explanations for why some people are catastrophists and others not; his theory seems to explain why there is a link between egalitarian group values and catastrophist thinking and between competitive individuals/markets and non-catastrophist thinking.

Decisionmaking about risk is tricky. Often risk discussions are actually proxies for ideological discussions, and in government programs about risk often become hijacked by various interests. Rayner's theory shows how different groups "like" different levels of uncertainty and stakes: the catastrophist egalitarians prefer high stake or high uncertainty issues since they tend to require the ideological/value based approaches they favour, technocrats like to reduce stakes and uncertainty so their solutions work and the market people like the intermediate realm where individual solutions can be tried.

We might be in a window of opportunity. Risks from nanotechnology, AI and biotechnology are not yet large. This means we can actually try to come up with sensible safeguards before they happen, informed by past experiences with handling other risks like terrorism. There seems to be some new nuclear disarmament approaches, and people are willing to consider various approaches on climate change (as long as they involve sack cloth and ashes, and not geoengineering or someone getting rich from them).

All in all, there is a lot to do now. We have a rough map of the field of global catastrophic risks, we have some rough ideas of levers to pull and attractor states to understand better. Given the lack of studies on this level there is a great deal of opportunity - and we better make use of it.

July 23, 2008

The Graphs of War

Correlates of War attempts to collect data on international relations. During the recent conference on global catastrophic risks I started playing with their data on wars, coming up with the following graphs.

(Download PDF file with names)

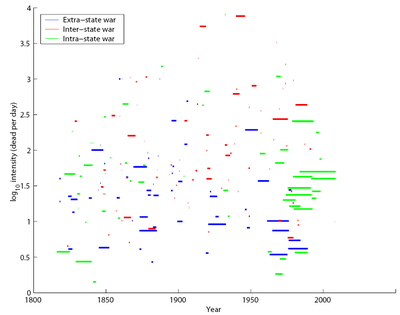

Here I have plotted each conflict as a bar, with length indicating when it occurred. Color denotes the type of conflict, with blue colonial wars, red nation-nation was and green ones as civil wars. On the vertical axis is the intensity, measured as dead per day.

The two world wars stand out at the top, with the equally intense (but rather forgotten) El Salvador 1932 war. There does not seem to be any strong correlation between intensity and time. The green wave to the right corresponds to various independence movements that started fighting in the 60's and 70's.

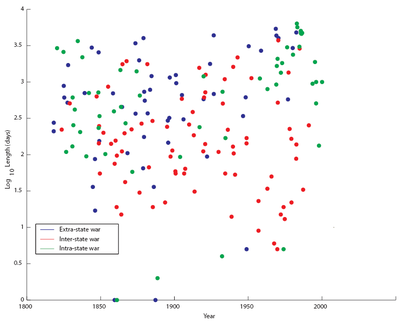

Have wars become longer or shorter? This plot shows the length depending on when the war occurred. It looks like wars 1900-1950 tended to be shorter than older and more recent ones. In particular some independence struggles drag on and on. Few wars are shorter than a month, but there are one-day wars.

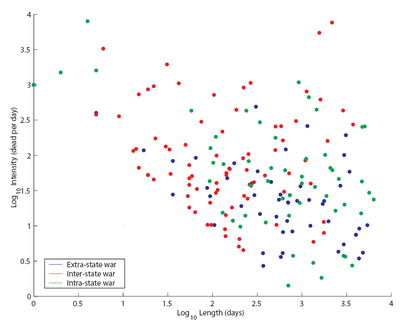

Plotting length versus intensity shows a cut-off in the data: conflicts below the lower left line are below the radar. There also seems to be a tendency for colonial and civil wars to drag on (presumably due to the use of guerrilla tactics) while inter-state wars are quicker and more intense.

From a global catastrophic risk perspective it is the big wars that are the main risk, from a personal life project perspective it is the nasty civil wars that tend to ruin people's lives and ability to flourish.

July 11, 2008

Idiocracy, 18th Century Style

Sometimes things just click together in my academic surfing and I find how many unrelated references I had previously not thought about actually are connected. While looking up the concepts related to baroque theater (just for game use, honest!) I found myself in the realm of Restoration (and subsequent) art critic, which led me to Pope's satires.

Sometimes things just click together in my academic surfing and I find how many unrelated references I had previously not thought about actually are connected. While looking up the concepts related to baroque theater (just for game use, honest!) I found myself in the realm of Restoration (and subsequent) art critic, which led me to Pope's satires.

Not being of a literary bent I had never encountered Pope's Dunciad before. It is a very fun read, an equal mixture of satire against literary enemies and fears about the dumbing down of early 18th century Britain.

The basic story is that the goddess Dulness, goddess of stupidity, is recruiting Lewis Theobald (literary rival of Pope) as her new king and showing him how the war against quality, learning and independent thinking progresses with the help of nonsense, hired pens and bad writing. "While pensive Poets painful vigils keep,/ Sleepless themselves to give their readers sleep" The literary marketplace is full of idiots, flatterers and profiteers selling whatever sells, priming the public to want more spectacle rather than better works. Academia is either promoting whatever fits the rulers, or losing itself in irrelevance:

Beneath her foot-stool, Science groans in chains,

And Wit dreads exile, penalties and pains.

There foam'd rebellious Logic, gagg'd and bound,

There, stripp'd, fair Rhetoric languish'd on the ground;

His blunted arms by Sophistry are borne,

And shameless Billingsgate her robes adorn.

Morality, by her false guardians drawn.

Chicane in furs, and Casuistry in lawn,

Gasps, as they straiten at each end the cord,

And dies, when Dulness gives her page the word.

Mad Máthesis alone was unconfined,

Too mad for mere material chains to bind,

Now to pure space lifts her ecstatic stare,

Now running round the circle, finds it square.

It doesn't seem that much has changed since then. Including that it is hard for poets to tell when science is very relevant (Pope jokes several times about the study of fleas, which in time of course turned out to be quite important - not to mention the "mad" mathematics above).

In the end the "translatio stultitia", the progress of idiocy (a concept related to the renaissance idea of translatio studii, that learning forms a wave moving westwards - incidentally a concept Robert Anton Wilson filed off the serial numbers from and used in a few of his books) will overwhelm what little learning has been amassed:

How little, mark! that portion of the ball,

Where, faint at best, the beams of Science fall.

Soon as they dawn, from Hyperborean skies,

Embody'd dark, what clouds of Vandals rise!

It is interesting that the often quoted ending lines,

Lo! thy dread empire, Chaos! is restored;

Light dies before thy uncreating word:

Thy hand, great Anarch! lets the curtain fall;

And universal darkness buries all.

actually refers to the triumph of lack of reason and quality, not just chaos or entropy in general. Pope was seriously worried that stupid memes were outbreeding the good ones ("Behold a hundred sons, and each a dunce"). Memetic dysgenics is always more pressing than genetic dysgenics - the generation time for memes is faster.

It is still a very fun poem (with plenty of very dirty jokes in the second book) but also a good reminder that the eternal war on stupidity has to go on. We cannot leave the enlightenment to sputter out - or think it wasn't ribald, violent and fun too.

July 01, 2008

Crime Doesn't Pay but Education Does

On ethics in the news I blog about Education and the Fairness of Capital Punishment - a small neural network study has shown that it is possible to predict who on death row who will be executed based on non-crime factors, such as education. Yet another problem for the supporters of capital punishment and more evidence that education (or a high g) pays off.

On ethics in the news I blog about Education and the Fairness of Capital Punishment - a small neural network study has shown that it is possible to predict who on death row who will be executed based on non-crime factors, such as education. Yet another problem for the supporters of capital punishment and more evidence that education (or a high g) pays off.

It seems that most ways of fixing it doesn't preserve fairness or due process: executing everybody within a set time would be fair within the set of condemned but lead to more wrongful executions which are unfair to all of society. Giving assistance to the least able condemned to do their appeals would likely cause more subtle unfairness depending on ability to make use of this assistance, and so on. I guess a pro-capital punishment person could simply regard the small unfairness of some convicts being able to get a better deal is simply worth it.

But while the unfairness of the educated convicts surviving better may have people talking, most ignore the even larger unfairness that males are executed over females. Here is an inequality that is apparently regarded as acceptable for no good reason.