November 25, 2008

The blue pills of Mount Everest

I blog on Practical Ethics: Keeping Viagra in the bedchamber and out of the arena? about the recent investigations of whether sidenafil could work as doping. My conclusion is that it may actually be a way of increasing fairness in sports.

I blog on Practical Ethics: Keeping Viagra in the bedchamber and out of the arena? about the recent investigations of whether sidenafil could work as doping. My conclusion is that it may actually be a way of increasing fairness in sports.

Outside of sports, if the results hold up, this might actually be practical for mountaineers or people going to high altitude environments. But the (ehum) side-effects might of course complicate a climb.

Calling BS

Wendy Grossman has a nice essay, The art of the impossible (that I found since she quotes me) about how to tell plausible fantasy from wild possibility.

Wendy Grossman has a nice essay, The art of the impossible (that I found since she quotes me) about how to tell plausible fantasy from wild possibility.

I think that is a very interesting and tricky problem. We need to do it every day (especially if one is moving in future-oriented circles), but doing it well is hard.

I think the key is to have a sequence of attention filters. Just like most spam, most bad ideas can easily be detected by just looking at keywords or form. Somebody claiming a fundamental insight in physics who does not use a single equation or invents numerous new terms is very unlikely to be worth taking seriously. See the sci.physics crackpot index for a not entirely unworkable formalisation. In the Q&A part of a lecture, you can almost always tell who is going to ask the flaky questions (or rather, do their own rambling mini-lecture disguised as a "question") when they open their mouth - there is a lot of tone of voice, vocabulary and style that signals what is going to follow. On the upside, this kind of filtering is fast and takes minimal effort. On the downside, if you get the wrong patterns into your mental spam filter you will automatically dismiss categories of messages that are actually worth paying a bit more attention to.

There are some methods of deeper filtering that are popular but unreliable. Checking whether the source is a respected person might give help, but plenty of people say stupid things not just outside their specialities (where they are merely smart laymen) but even in them. Just consider the large number of things ascribed to Einstein. Looking for biasing interests might find reasons to suspect funding bias, self-interest or a tendency to self-deception, but could just as easily be an expression of our bias. We can also check whether a statement is likely to be a self-propagating meme spreading well because its coolness, emotional impact or other "dramatic" properties: if it is, we have a reason to think it is not necessarily truth-tracking. If it spreads because it fits evidence, then it has a better chance of being right (but availability bias can still make a false idea spread effectively under the right conditions).

The deeper filtering suggested by Merkle involves checking against known science (if it breaks stuff in elementary science it is very likely wrong) and checking it for internal consistency. This takes a lot more effort.

H.G. Frankfurt made a good point in that people who are talking bullshit are uninterested in truth: liars and truthful people pay attention to it, but bullshitters care more about the form and appearance of what is said than any real content. So detecting when somebody is bullshitting (it is always a process) is a good way of checking the value of the ideas. Calling bullshit sometimes work: ask the source for details, check whether they actually understand what they say and if they can elaborate the ideas. But delusional and lying people are pretty good at answering challenges. Also, calling bullshit can also be a social strategy to appear critical or clever rather than a way of elucidating the value of ideas.

Wendy arrives at the conclusion that the real thing to look for is deliverables. That may be useful even when the real deliverables (AI, nanoassemblers, life extension) remains in the future: most real work produce deliverables of other kinds before it achieves success. There is a difference between the inventor slaving away in his workshop and the one talking on the internet about the importance of his work. A nanoassembler project will produce papers and prototypes that give evidence of progress (again, these should ideally be scrutinized for actual content, of course). The SENS program is sponsoring real research in particular areas that follow logically from its aims. Meanwhile most purveyors of herbal remedies seem to be very uninterested in actually testing their products strictly.

Overall, the effort that should go into checking whether something is worth taking seriously should be proportional to our prior estimate that it actually is true, the importance it would have if true, and how much effort we can save by investigating it.

November 10, 2008

Make research (not so) fast!

On practical ethics I blog about Hacking the spammers - was it OK for researchers to hack the Storm botnet? Overall, I think they did the ethical thing and should be lauded for a clever design and much hard work at a major annoyance.

On practical ethics I blog about Hacking the spammers - was it OK for researchers to hack the Storm botnet? Overall, I think they did the ethical thing and should be lauded for a clever design and much hard work at a major annoyance.

In fact, botnets are more than annoyances. They are tools for aggregating resources in the hands of organized Internet crime and can be used for plenty of serious things such as extortion, DDOS on a national level, rapid dissemination of disinformation or cryptographic attacks. If I were the cyberwarfare department of a major nation (or mafia, NGO, rebel group, cult, etc) I would be quite interested in having a bunch of exploits that could allow me to set up a botnet in case of a conflict. Having good tools to curb the spread of botnets is essential for preventing destructive cyberwarfare and "antisocial software".

I think cyberwarfare is an underestimated GCR. The real threat is not a straight DDOS or hacking attacks on key institutions (but such attacks could cost the US on the order of $50 billion or more), but either a general communications breakdown or information corruption. Consider a worm propagating through or exploiting a router flaw that causes the routing of Internet to largely go down: it would be very hard to ship out patches and install them, and in the meantime overall societal communications would be impaired. In a "just in time" economy dependent on reliable communications between and inside organisations this could be disastrous. More subtle is the possibility of hard-to-trace data corruption, for example changing individual numbers in office documents randomly on infected computers. If the infiltration is widespread and hard to notice data integrity might be impaired across society. While each individual loss would be relatively minor, there could be network effects where the loss of integrity on many systems simultaneously has a superadditive effect.

We need to figure out how to construct more resilient systems, not only in the sense that the systems in themselves are resilient to outside attacks but also that they form an ESS so that people are motivated to keep their systems resilient. Otherwise there is a risk that they trade resiliency for short-term efficiency increases.

November 06, 2008

(In)Security Maxims

Physical Security Maxims (via Crypto-gram)

Physical Security Maxims (via Crypto-gram)

Plenty of sound advice, although they overlap quite a bit. Given this list the main causes of security flaws appear to be mainly organisational and due to cognitive bias - hardly surprising, but always a shock when they happen.

November 03, 2008

Under the eye and criticism of the public

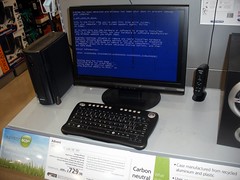

I have nothing in particular to say about the US election, except of course the computer/ethics side of it: Practical Ethics: Election ex machina: should voting machines be trusted?

I have nothing in particular to say about the US election, except of course the computer/ethics side of it: Practical Ethics: Election ex machina: should voting machines be trusted?

Unsurprisingly, I think we need more transparency and accountability in the election machine area. Security through obscurity is not going to work, and there is a risk of undermining democracy by undermining the trust of the vote. It is quite possible to make money from voting machines and have them inspected by everybody.

Ah, I forgot to include XKCD's always succinct explanation of what is wrong with much of current voting machine security. But I managed to get Bruche Schneier and John Stuart Mill into the same post.

Something hopefully completely unrelated: at the same blog, Matt, Julian and me have a short essay about Should We Be Erasing Memories?.