March 19, 2011

Cities are the coral reefs of humanity

Some self advertising: Transhuman Space: Cities on the Edge is now sold on e23. A module for the roleplaying game written by me and Waldemar Ingdahl.

Some self advertising: Transhuman Space: Cities on the Edge is now sold on e23. A module for the roleplaying game written by me and Waldemar Ingdahl.

This has been loooong in coming. Due to a large number of individually trivial causes it has been delayed enormously. But now it is out!

The theme is the city of the future. Not just as a setting for adventures (although they are good for it), but as a concept. Just what are cities good for, and will they survive in a future where people can telepresence from anywhere in the world? Our answer is that cities will remain because they are efficient, they have cultural and economic cluster effects, and they are anchored as memes.

One problem with delays is that science and ideas change. When we wrote it we were influenced by the New Urbanism and Richard Florida. If we wrote it today I suspect we would be using even more Geoffrey West. However, I am still pretty happy with it, and I think our ideas fit with the scaling ideas (basically, West, Bettencourt et al. quantify the economics of scale of cities, and show that they may be driving the rapid growth of super-cities - a rapid growth forcing technological innovation in order to be sustainable). Another experience I have had since writing it is seriously living in a foreign city and culture (OK, slightly foreign - still Northwest European), which shows how small aspects of space and cultural syntax can complicate things - not just people driving (and walking) on the other side of the road, but the different assumptions of what homes and third places are, as well as the parapraxes of infrastructure.

What else is there? A lot deals with how future infrastructure works: when you have AI, nanotech and robots, what does that do to cities? What new kinds of infrastructure do you need? (for example, cities may gain augmented reality layers and relatively cheaply dug tunnel systems for delivery from large-scale fabbing - not all fabbing is going to be local and personal) What are the big threats to such cities? How do people, buildings and cities adapt to changed requirements? (with good telepresence, parks and cafes become more important than offices - so they might eat much of the freed up office space)

A lot of details are about everyday life, the small things that make the game setting alive. Animated or biological graffiti, the AI suburbs, how to deal with free riders in smart transport systems, mothballed buildings and who lives inside, the problems of running a biotech house and what kinds of wood you can order from a vat.

There is also a big section about future Stockholm, a wild and slightly bohemian city acting as a pressure valve for transhumanists inside the staid preservationist Scandinavian societies. Think Berlin after the fall of the Wall - cheap accommodation and slightly rickety infrastructure, lots of counter-culture people that exploit it and make it a happening place to the shock and annoyance of the staid people outside.

All in all, it is not just intended as a rpg sourcebook (although that was of course the main intention) but as a bit of ongoing scenario planning of where we might be going. The cities will remain, but they are going to evolve.

March 18, 2011

Are novels getting longer

In my previous post I made some claims about novels not getting shorter. Here is some evidence for them.

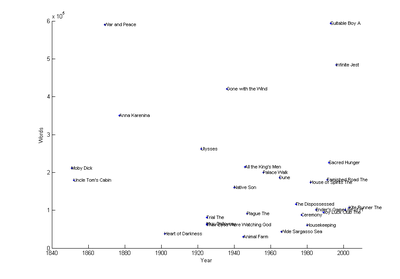

Looking at the lengths mentioned on length of a novel in Wikipedia produces this graph (excluding the very early The Tale of Genji):

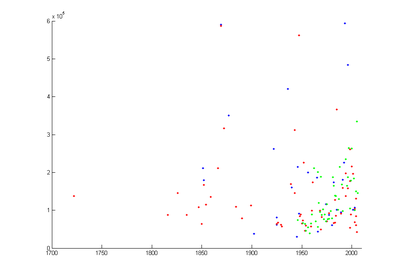

No clear trend. Adding some novel lengths I found mentioned on other pages produces this extended scatter plot:

No obvious trend, although maybe the shortest novels have become longer until a peak in the 1990s and now are becoming shorter again. Methodologically this is iffy, since we have no guarantees that my sources have been listing representative novels. Since different genres tend towards different lengths, this is a mix of apples and oranges.

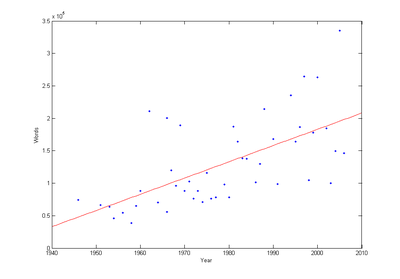

However, let's look at one genre over time: science fiction. I took the Hugo prize winning novels I could measure (not all are included, but I think the factors causing exclusion - mostly me having them in the wrong file format - are uncorrelated with anything important) and plotted their length against when they won. The result is promising:

For every year the winner tends to be 2,504 words longer. So I think we can at least say that some genres are getting longer novels.

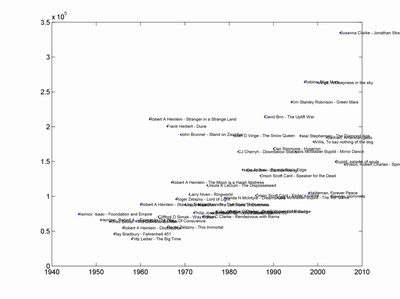

Here are the names of the novels:

March 17, 2011

Rational short attention spans

(Attention conservation summary: attention spans have not become shorter, there are simply so much more good information out there that it is rational to jump around more to find something truly engrossing)

Do we really have shorter attention spans now than in the past? It certainly *feels* that way, but a few years in Oxford and too much cognitive bias literature has made me distrust my own judgement.

Do we really have shorter attention spans now than in the past? It certainly *feels* that way, but a few years in Oxford and too much cognitive bias literature has made me distrust my own judgement.

If we really had short attention spans, we should expect the average book to become far shorter (and book sales go down in preference for comics). This does not seem to happen: book sales are up and books doesn't seem to get shorter. In fact, the spread of multi-volume fantasy novels with casts of hundreds of characters seem to be a pretty convincing argument that young people are able to pay significant attention.

Book length seems to be more driven by economic factors and that word processors allow authors to write more. Looking around the net I see that some writers claim there is a new trend towards shorter novels again because of economic reasons of bookstore shelf space, but ebooks could certainly change that. Different genres also have different preferred word counts

Similarly, films have for technical reasons become able to be epic in length, and I assume there are economic reasons too (how much would you pay for a ticket to a 50 minute film?). Yet the clipping has become far faster - seeing young people encounter Kubrick's 2001 for the first time is instructive. They better not try Tarkovsky's Solaris.

So my theory is that we can still pay attention for a long time - but we want a lot more to happen per unit of time too. We want faster rewards, more action.

Why? Perhaps because there is so much stuff out there, so the alternative cost of spending a lot of time on something that does not turn out to be worthwhile is higher. In the time you have spent reading this post (and I writing it) we could have read several RSS entries and short blog posts, watched a YouTube clip, browsed Wikipedia or run a calculation in our favourite math program.

Why? Perhaps because there is so much stuff out there, so the alternative cost of spending a lot of time on something that does not turn out to be worthwhile is higher. In the time you have spent reading this post (and I writing it) we could have read several RSS entries and short blog posts, watched a YouTube clip, browsed Wikipedia or run a calculation in our favourite math program.

[ Why did we in the past not cram more action into our films and novels? To some degree we did: 19th century novels often had a large number of plot twists since they were published in instalments. But there was far less competition: books were expensive and had to be fetched from the library, there were few films, there were fewer competing media. There were also limits to the complexity the readers and viewers could take in: today we have media experience that allow us to simply chunk much of standard stories (we are thinking in tropes!) Maybe the old media were more free and nuanced while modern media relies on triggering various known symbols and references (a digital mode), but that nuance also required a slower pace for the "analogue" information to be transmitted. See for example Narrative Complexity in Contemporary American Television by Jason Mittell and Watching TV Makes You Smarter by Steven Johnson. ]

[ One reason there is so much worry about shortening attention spans might be that we live in a society where high status activities increasingly involve focusing on highly abstract material, and being distractable is seen as a problem. Instead of looking at the distraction, motivation and task switching itself, a reified attention span is invoked (see The Attention-Span Myth by Virginia Heffernan)]

If this model is true, then we should expect the trend to continue. In the future, we are going to have far more good books, films, comics, papers and other documents instantly available.

It is rational to demand quick and reliable evidence that whatever we have in front of us is relevant or interesting. Spending a lot of time finding out if it actually is by just consuming it would mean we would often waste precious time and attention on things that are not as good.

There is of course a trade-off here, since some important things do not look inviting (since they were made before the current attention economy) and some unimportant things masquerade as important. Smart agents balance the exploration with exploitation.

This is why reliable filtering and reviewing actually are key transhuman technologies. And why training to recognize the real cost and value of what you are doing is such a key transhuman virtue.

March 15, 2011

Confidence

Here is an important insight from the webcomic Saturday Morning Breakfast Cereal:

This is why I don't trust confident people and why I am in favour of radical life extension.

From a Bayesian standpoint maybe this kind of behaviour can be explained by the growth of the number possible hypotheses and the accumulation of evidence (beside the obvious irrational biases, of course). At first we have few hypotheses to choose between, and new evidence makes us more confident in one or a few. Then we start seeing the possibility of more hypotheses, and now the accumulating evidence starts to update a much broader field of hypotheses. In the really long run we finally get over the explosion of possibilities and start to zoom in on the best ones again.

Presumably this would be different in different domains. In simple domains there will be few possible alternative hypotheses and confidence will just increase. In domains with little evidence accumulation but easily generated hypotheses confidence will tend to decrease. Examples of such domains are left as an exercise for the reader.

March 12, 2011

A tale of two reactors

A tale of two reactors - I blog about the Fukushima incident, and what comparing it to the Chernobyl incident tells us about the importance of personal media and the open society.

A tale of two reactors - I blog about the Fukushima incident, and what comparing it to the Chernobyl incident tells us about the importance of personal media and the open society.

I had a moment of clarity when I noticed that I am actually sitting in the same chair, in the same corner of my mother's flat right now as I was when I heard about the Chernobyl incident. Yes, I am still in front of a computer, a few thousand times more capable than the first one. And I am getting news a thousand times faster, with more diversity and with better consistency checking thanks to the Internet than through that single radio channel I once listened to. Far from perfect, but we are getting there. Especially since there are now far more people around who can report, not just better transmission of the reports.

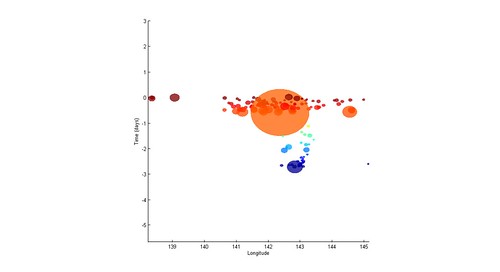

Visualizing the March 2011 quake

A quick visualization of the USGS data on the earthquakes around the big March 11 2011 earthquake in Japan:

Looking at the pattern across time, there were some precursors cascading over the previous two days, then the massive one and a widely spread network of aftershocks:

At least Japan is a resilient, well-off society with past experience with quakes and tsunamis - it could have been much worse. Which is not much of a comfort.

March 11, 2011

I am a language

One of my secret shames as a computer scientist is that I have never written a programming language. I think that to be a proper computer scientist you have to have written a parser and then used it to implement some more or less silly language. I might get around to it someday, and then I can say "Now I am a *real* computer scientist."

One of my secret shames as a computer scientist is that I have never written a programming language. I think that to be a proper computer scientist you have to have written a parser and then used it to implement some more or less silly language. I might get around to it someday, and then I can say "Now I am a *real* computer scientist."

However, thanks to Toby Ord I have achieved the next best thing: I have become a programming language: Anders.

The language specification is interesting, especially this point:

A word of warning. Anders is the only language I know of to feature compile-time nondeterminism. That is, the results of two compilations of the very same source file might differ. Indeed, it might cause an error (or non-termination) one time, but work fine another time. Luckily, Anders is bound by a promise that termination is guaranteed for compiling each prime numbered program. That is, the 2nd, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 11th… programs sent to Anders will either successfully compile, or will at least return an error message of some sort.

The real trick is of course to know what my program counter is. Which actually makes me a stateful compiler language, another weird first.

(This all began as a joke during a session in the FHI sofa where I was building and testing a simulation for a SETI-related problem while interacting with Toby and Nick. I highly recommend this kind of "extreme development" where you develop code for small simulations interactively. It was almost like using the computer as a whiteboard.)

March 06, 2011

You never forget your first

I just realized that is is the 30 year jubilee of the Sinclair ZX 81 computer. It was my first computer. I had already spent over a year writing programs on slips of paper, based the books I found in the library, and finally my parents decided to get rid of them by giving me a computer.

Ah, the wonder of connecting it to the television set and writing a simple hello world program! How many days and nights I tinkered with small simulations and games! The struggle to avoid too much interference from television channels on the screen - I was forced to stop in the late afternoon when the two television channels went on air. System crashes when you nudged the desk the computer stood on and the 16K expansion memory wobbled. A 44x60 pixel Mandelbrot program that took all night. Careful coding to fit programs and data into memory. Poking directly into memory to make "copy protected" lines of code.

This was the computer that made me realize why spaghetti code is bad. I understood dimly the need for object oriented programming as I struggled to maintain data structures across several arrays. I was sitting at my desk working with the radio on P1, accidentally picking up plenty of world knowledge (and one memorable day when I was home from school due to a cold, the unfolding of the Chernobyl disaster - from the first news report of an alarm at the Forsmark nuclear power plant to the final confirmation that something had happened in the Soviet union).

As I got a graphics extension module - 256x192 points resolution! - I began to seriously experiment with computer graphics. I was by no means a power user - BASIC was enough for me, I never learned to do assembler - but this was my first mental extension. When I wondered over a mathematical problem I would try it out on the computer, a habit I have cultured over the years (you can learn quite a lot from just implementing a crude simulation, even if it never gives any data).

I still got it. It is stored safely in a box in Stockholm together with its successor ZX Spectrum, a tape recorder for loading programs, the thermoelectric printer that burned printouts on aluminized paper with tiny sparks, and several tapes that at least once contained my childhood programs.

March 02, 2011

Ice cream like mother used to make

Being a food empiricist willing to try anything survivable at least once, I was intrigued by the reports about a London ice cream parlour selling ice cream made with human milk. Unfortunately they were stopped (for now). But here is a post about my thoughts on the ethics of using human milk in food.

Being a food empiricist willing to try anything survivable at least once, I was intrigued by the reports about a London ice cream parlour selling ice cream made with human milk. Unfortunately they were stopped (for now). But here is a post about my thoughts on the ethics of using human milk in food.

Basically, as long as they can maintain food safety (you do want to avoid hepatitis viruses) there doesn't seem to be any morally wrong with it to me.

I guess this is a bit like the discussions about whether eating cultured human meat would be cannibalism. Old yuck factors getting in the way of enjoying life. Made even more problematic by a highly diverse society where people have wildly different perspectives.