January 03, 2012

Ethics and function approximation

(This started as a post on the Extropians list)

On 2012-01-01 12:55, Stefano Vaj wrote:

> I do think that utilitarian ethical systems can be consistent, that is

> that they need not be intrinsically contradictory, but certainly most of

> them are dramatically at odd with actual ethical traditions not to

> mention everyday intuitions of most of us.

Of course, being at odds with tradition and everyday positions doesn't tell us much about the actual validity of a position. Which brings up the interesting question of just how weird a true objective morality might be if it exists - and how hard it would be for us to approximate it.

Our intuitions typically pertain to a small domain of everyday situations, where they have been set by evolution, culture and individual experience. When we go outside this domain our intuitions often fail spectacularly (mathematics, quantum mechanics, other cultures).

A moral system typically maps situations or actions to the set {"right", "wrong"} or some value scale. It can be viewed as a function F(X) -> Y. We can imagine looking for a function F that fits the "data" of our normal intuitions.

(I am ignoring the issue of computability here: there might very well be uncomputable moral problems of various kinds. Let's for the moment assume that F is an oracle that always provides an answer.)

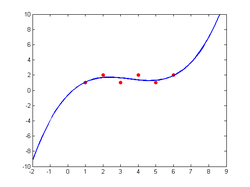

This is a function fitting problem and the usual issues discussed in machine learning or numerics textbooks apply.

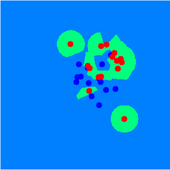

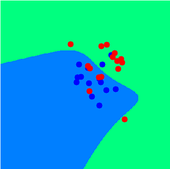

We could select F from a very large and flexible set, allowing it to perfectly fit all our intuitive data - but at the price of overfitting: it would very rapidly diverge from anything useful just outside our everyday domain. Even inside it would be making all sorts of weird contortions in between the cases we have given it ("So drinking tea is OK, drinking coffee is OK, but mixing them is as immoral as killing people?") since it would be fluctuating wildly in order to correctly categorize all cases. Any noise in our training data like a mislabelled case would be made part of this mess - it would require our intuitions to be exactly correct and entered exactly right in order to fit morality.

We can also select F from a more restricted set, in which case the fit to our intuitions would not be perfect (the moral system would tell us that some things we normally think are OK are wrong, and vice versa) but it could have various "nice" properties. For example, it might not change wildly from case to case, avoiding the coffee-mixing problem above. This would correspond to using a function with fewer free parameters, like a low degree polynomial. This embodies an intuition many ethicists seem to have: the true moral system cannot be enormously complex. We might also want to restrict some aspects of F, like adding reasonable constraints like the axioms of formal ethics (prescriptivity ("Practice what you preach"), consistency, ends-means rationality ("To achieve an end, do the necessary means") - in this case we get the universalizability axiom for free by using a deterministic F) - these would be constraints on the shape of F.

The problem is that F will behave strangely outside our everyday domain. The strangeness will partly be due to our lack of intuitions about what it should look like out there, but partly because it is indeed getting weird and extreme - it is extrapolating local intuitions towards infinity. Consider fitting a polynomial to the sequence 1,2,1,2,1,2 - unless it is constant it will go off towards positive infinity in at least one direction. So we might also want to prescribe limiting behaviours of F. But now we are prescribing things that are far outside our own domain of experience and our intuitions are not going to give us helpful information, just bias.

Attempts at extrapolating a moral system that can give answers for any case will hence either lead to

- Fit with our moral intuitions but severe overfitting, complexity and lack of generalization to new domains.

- Imperfect fit with our moral intuitions and strange behaviour outside our normal domain. (the typical utilitarian case)

- Imperfect fit with our moral intuitions and apparently reasonable behaviour outside our normal domain, but this behaviour will very likely be due to our current biases and hence invalid.

Not extrapolating will mean that you cannot make judgements about new situations (what does the bible say about file sharing?)

Of course, Zen might have a point:

'Master Kyogen said, "It is like a man up a tree who hangs from a branch by his mouth. His hands cannot grasp a bough, his feet cannot touch the tree. Another man comes under the tree and asks him the meaning of Bodhidharma's coming from the West. If he does not answer, he does not meet the questioner's need. If he answers, he will lose his life. At such a time, how should he answer?"'

Sometimes questions have to be un-asked. Sometimes the point of a question is not the answer.

My own take on this is exercise is that useful work can be done by looking at what constitutes reasonable restrictions on F, restrictions that are not tied to our moral intuitions but rather linked to physical constraints (F actually has to be computable in the universe, if we agree with Kant's dictum "ought implies can" ought should also imply "can figure it out"), formal constraints (like the formal ethics axioms) and perhaps other kinds of desiderata - is it reasonable to argue that moral systems have to be infinitely differentiable, for example? Can the intuition that moral systems have to be simple be expressed as a Bayesian Jeffreys-Jaynes type argument that we should give a higher prior probability to few parameter moral systems?

This might not tell us enough to determine what kind of function F to use, but it can still rule out a lot of behaviour outside our everyday domain. And it can help us figure out where our everyday intuitions have the most variance against less biased approaches: those are the sore spots where we need to investigate our moral thinking the most.

Another important aspect is for investigating AI safety. If an AI were to extrapolate away from human intuitions, what would we end up with? Are there ways of ensuring that this extrapolation hits what is right - or survivable?

Posted by Anders3 at January 3, 2012 07:12 PM