August 30, 2013

Finding the arms of the real(er) near star map

As I mentioned way back, the old roleplaying game 2300AD and its updated version 2320AD are close to my heart. Hard science fiction, a well developed setting, and some interesting conflicts make for a very good game.

As I mentioned way back, the old roleplaying game 2300AD and its updated version 2320AD are close to my heart. Hard science fiction, a well developed setting, and some interesting conflicts make for a very good game.

However, realism also has its problems: the star map is intended to be as correct as possible, but the assumption of the FTL drive that gives the setting its particular flair (travel is limited to 7.7 lightyears) also means it is very sensitive to star locations. Move a star a few lightyears, and the network of reachable stars changes tremendously. As explained in my old post, this is because 7.7 lightyears is close to the percolation transition in this case: any shorter, and most stars can only reach a few others in an isolated cluster, any longer and most stars are now in one giant web where you can go anywhere. At the transition the network is complex and interesting, but also strongly affected by updated star positions.

Now, the Evil Dr Ganymede, being an astronomer, has created an amazing database based on our current best estimates of nearby stars:

- [2300AD] Realistic Near Star Map Project: Part I – Introduction

- [2300AD] Realistic Star Map Project: Part II – Overview

- [2300AD] Realistic Star Map Project: Part III – The New French Arm

This includes nearby brown dwarves, which act as important stepping stones, and also updated distances.

Dr Ganymede is trying to fit the good old 2300 setting to the new maps. I wish him the best of luck - he has done ingenious work. In most cases it is possible to reassign planets to other stars, especially since most outposts are barely described and can easily be moved from one red dwarf to another. But still, it is a major effort.

I take a different view, since I like inventing entirely new settings (and stealing/borrowing good ideas from others). Just what kind of world does his database imply?

Here are my maps of the stars reachable from the sun (~1.5 Mb PDF files):

- Spatial map, showing the links and spectral type

- Network map, laid out by force directed graph layout

- Natural clusters and betweeness centrality

- Radial network map

Some observations:

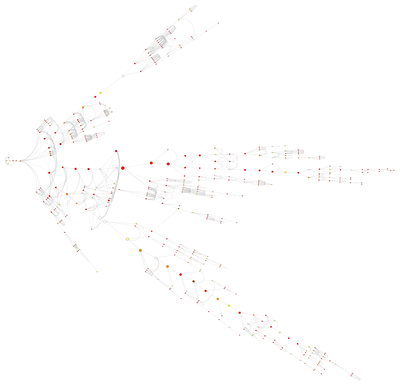

The sun is in its own little cluster with Alpha Centauri, Proxima and Barnard's Star, linking up to the big network via Ross 154 and AX Microscopii - those two stars are very strategic and can act as chokepoints for the sol cluster.

The Delta Pavonis cluster involves a lot of the classic nearby stars, linked fairly densely - Tau Ceti, Epsilon Eridani, Epsilon Indii, Delta Pavonis. It in turn links to several clusters - a branch towards 54 Piscium, the 36 Ophiuchi cluster, and the Sirius cluster.

The Sirius cluster is the other "nearby" cluster, containing Sirius and Procyon. It also has DX Cancri, which is a very strategic link to the Arcturus cluster and Beta Canum cluster - what in the old 2300AD would be the French Arm. The Sirius cluster also links to the Tabit (Pi 3 Orionis) cluster.

The overall structure, looking out from the sun (this is clearest in the radial map), is that there are indeed three big arms.

-

One, starting at WD 0553+053, expands via Pi 3 Orionis and Delta Eridani, stretching out branches towards Delta and Zeta Trianguli Australis, Tau Piscis Austrini and Zeta Reticuli. It has fingers towards Pollux and Gamma Leporis, as well as many other directions. I guess this is the closes counterpart to the Chinese arm in the original setting.

The second is the DX Cancri "French arm", stretching towards Arcturus along the main branch and with a smaller branch towards Beta Canum and Xi Ursae Majoris. It has interesting non-standard sub-arms, like towards Alpha Mensae and Alpha Corvi.

The third one starts at Mu Herculis, becoming the default "American arm". It runs towards Eta Cassiopeia.

Overall, the structure does seem reminiscent of a Core, a Near Space, and then arms expanding outwards. Thinking of centralized control, unless the communications are very long-distance and fast, it will be hard to control the systems out in the arms from the sun. Near Space is much easier, especially since cross-communication works well.

The clusters tend to be either dense meshes or linear stretches (likely because they are far out, see below; there should actually be more stars in them). They have on average two or three neighbouring clusters, linked by gateway stars.

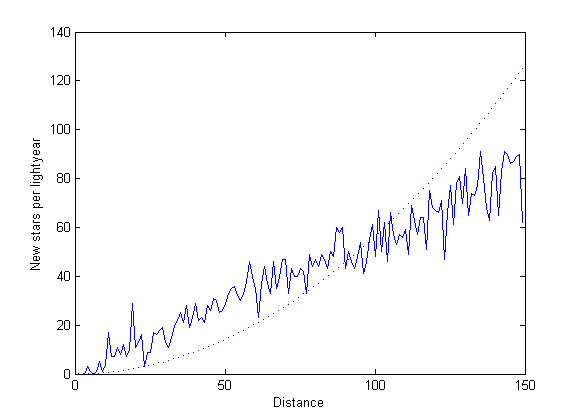

I limited the search out to 70 lightyears, mainly because the density falls off, making the percolation stop. It turns out that we have more observations of dim stars close to the sun than far away (shocking!). If you plot the number of stars within each 1 ly shell from the sun, it should on average grow quadratically. However, in the data it grows roughly linearly:

If it is possible to defend a system effectively, then the gateway stars make clusters relatively natural political or military units. Inside a cluster there are usually multiple paths one can take, allowing fleets to sneak around and do surprise attacks.

Given that stars move, clusters join and leave the network. Even a small motion can have significant effects if it is a gateway star. This is something I will be exploiting for an upcoming campaign: the Sol cluster has been isolated until recently because of the rapid motion of Barnard's star. This neatly explains why Earth has not been visited by aliens recently - a fun "explanation" of the Fermi paradox. In fact, it also allows an interesting galactic community: isolated clusters remain isolated for long stretches, allowing local intelligence to evolve. Eventually they touch the bigger network, and they get to interact with galactic culture... for good or ill.

August 23, 2013

The big sky

Silence in the sky – but why? - the oxford Science Blog brings up Stuart's and my paper on intergalactic colonization.

Silence in the sky – but why? - the oxford Science Blog brings up Stuart's and my paper on intergalactic colonization.

See also my earlier explanation of why we care, my TEDx talk and Stuart's original seminar. And my partial list of possible Fermi paradox explanations.

August 19, 2013

Some cheerful reading on apocalypses

Preventing Human Extinction by Nick Beckstead, Peter Singer, and Matt Wage - a very good brief explanation of just why reducing existential risk is such an important mission.

Preventing Human Extinction by Nick Beckstead, Peter Singer, and Matt Wage - a very good brief explanation of just why reducing existential risk is such an important mission.

I read it just after reading Rob Goodman's The Comforts of the Apocalypse (The Chronicle of Higher Education, August 19 2013). There he argues much apocalyptic thinking is about typology: finding meaning and a point to history, even if it ends with a bang or whimper. Dystopias are cozy, in a sense. Against that he puts 1984 and Stapledon's Last and First Men: he argues that they represent a Copernican view of history, where there might not be any point or pattern, yet there might still be local meaning rather than global meaning.

If one accepts that "leap of doubt" as Goodman calls it, should one care about existential risk? The nice thing about the prevention essay is that it doesn't build its argument on some global joint value of The Future of Humanity, the story of (human) evolution or progress. Instead it argues that causing people to come into existence can benefit them: their happiness or unhappiness is a local property, and it is better that there is a lot of it than less of it.

If we fail to prevent our extinction, we will have blown the opportunity to create something truly wonderful: an astronomically large number of generations of human beings living rich and fulfilling lives, and reaching heights of knowledge and civilization that are beyond the limits of our imagination.

Of course, one can be a pessimist and think that coming into existence is a net bad, or that human lives have sufficiently bad effects on other morally relevant entities that they are net negative.

I think pessimists of the first kind are simply wrong. They might be individually right - there are lives not worth living to their owners - but there are also good lives worth living. Again, the property of 'being worth living' is a local property rather than something universal or due to some big narrative of history.

Taking the second view just means we better become better, changing our relationship with other beings (e.g. using in vitro food or going autotrophic). Reducing existential risk by this account seem to be sensible, since if we die out before we stop causing harm we can never outweigh it.

Avoiding negatives is a bad motivator: our loss aversion might spur us more strongly into motion than possible gains, but it also feeds our anxieties making even success pale and worried. Trying to bring about something wonderful on the other hand fills us with dynamic optimism: maybe we will fail, but we will have enjoyed trying.