I have been working on the Fermi paradox for a while, and in particular the mathematical structure of the Drake equation. While it looks innocent, it has some surprising issues.

One area I have not seen much addressed is the independence of terms. To a first approximation they were made up to be independent: the fraction of life-bearing Earth-like planets is presumably determined by a very different process than the fraction of planets that are Earth-like, and these factors should have little to do with the longevity of civilizations. But as Häggström and Verendel showed, even a bit of correlation can cause trouble.

If different factors in the Drake equation vary spatially or temporally, we should expect potential clustering of civilizations: the average density may be low, but in areas where the parameters have larger values there would be a higher density of civilizations. A low may not be the whole story. Hence figuring out the typical size of patches (i.e. the autocorrelation distance) may tell us something relevant.

Astrophysical correlations

There is a sometimes overlooked spatial correlation in the first terms. In the orthodox formulation we are talking about earth-like planets orbiting stars with planets, which form at some rate in the Milky Way. This means that civilizations must be located in places where there are stars (galaxies), and not anywhere else. The rare earth crowd also argues that there is a spatial structure that makes earth-like worlds exist within a ring-shaped region in the galaxy. This implies an autocorrelation on the order of (tens of) kiloparsecs.

Even if we want to get away from planetocentrism there will be inhomogeneity. The warm intergalactic plasma contains 0.04 of the total mass of the universe, or 85% of the non-dark stuff. Planets account for just 0.00002%, and terrestrials obviously far less. Since condensed things like planets, stars or even galaxy cluster plasma is distributed in a inhomogeneous manner, unless the other factors in the Drake equation produce typical distances between civilizations beyond the End of Greatness scale of hundreds of megaparsec, we should expect a spatially correlated structure of intelligent life following galaxies, clusters and filiaments.

A tangent: different kinds of matter plausibly have different likelihood of originating life. Note that this has an interesting implication: if the probability of life emerging in something like the intergalactic plasma is non-zero, it has to be more than a hundred thousand times smaller than the probability per unit mass of planets, or the universe would be dominated by gas-creatures (and we would be unlikely observers, unless gas-life was unlikely to generate intelligence). Similarly life must be more than 2,000 times more likely on planets than stars (per unit of mass), or we should expect ourselves to be star-dwellers. Our planetary existence does give us some reason to think life or intelligence in the more common substrates (plasma, degenerate matter, neutronium) is significantly less likely than molecular matter.

Biological correlations

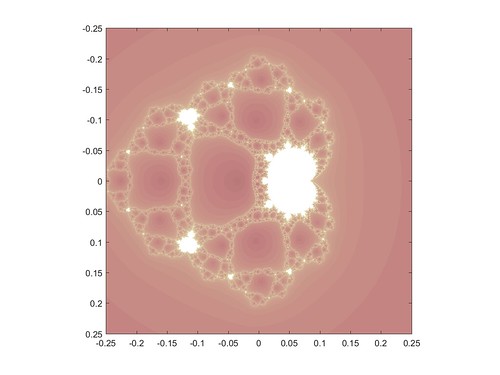

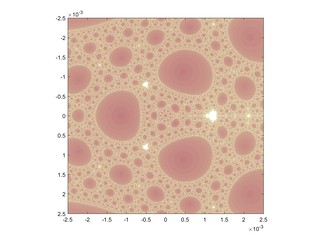

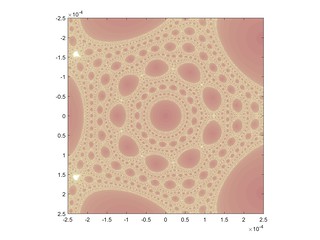

One way of inducing correlations in the factor is panspermia. If life originates at some low rate per unit volume of space (we will now assume a spatially homogeneous universe in terms of places life can originate) and then diffuses from a nucleation site, then intelligence will show up in spatially correlated locations.

It is not clear how much panspermia could be going on, or if all kinds of life do it. A simple model is that panspermias emerge at a density and grow to radius

. The rate of intelligence emergence outside panspermias is set to 1 per unit volume (this sets a space scale), and inside a panspermia (since there is more life) it will be

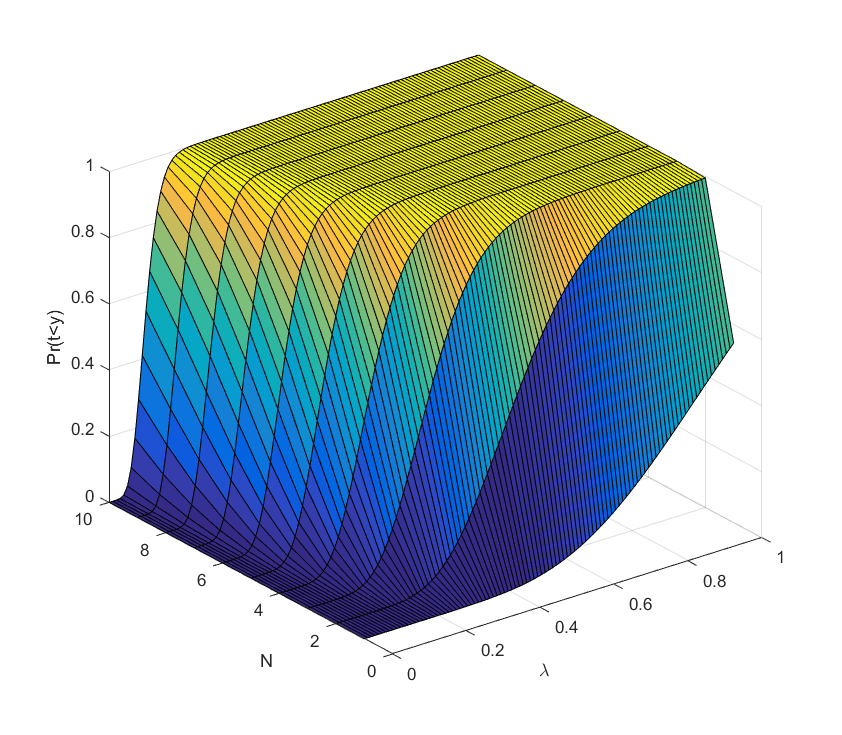

per unit volume. The probability that a given point will be outside a panspermia is

.

The fraction of civilizations finding themselves outside panspermias will be

.

As A increases, vastly more observers will be in panspermias. If we think it is large, we should expect to be in a panspermia unless we think the panspermia efficiency (and hence r) is very small. Loosely, the transition from going from 1% to 99% probability takes one order of magnitude change in r, three orders of magnitude in and four in A: given that these parameters can a priori range over many, many orders of magnitude, we should not expect to be in the mixed region where there are comparable numbers of observers inside panspermias and outside. It is more likely all or nothing.

There is another relevant distance beside , the expected distance to the next civilization. This is

where

is the density of civilizations. For the outside panspermia case this is

, while inside it is

. Note that these distances are not dependent on the panspermia sizes, since they come from an independent process (emergence of intelligence given a life-bearing planet rather than how well life spreads from system to system).

If then there will be no panspermia-induced correlation between civilization locations, since there is less than one civilization per panspermia. For

there will be clustering with a typical autocorrelation distance corresponding to the panspermia size. For even larger panspermias they tend to dominate space (if

is not very small) and there is no spatial structure any more.

So if panspermias have sizes in a certain range, , the actual distance to the nearest neighbour will be smaller than what one would have predicted from the average values of the parameters of the drake equation.

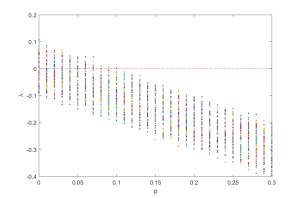

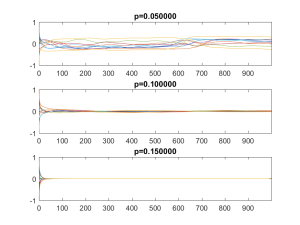

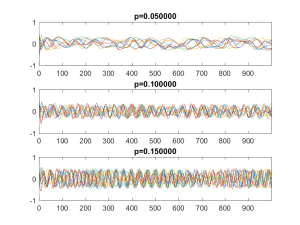

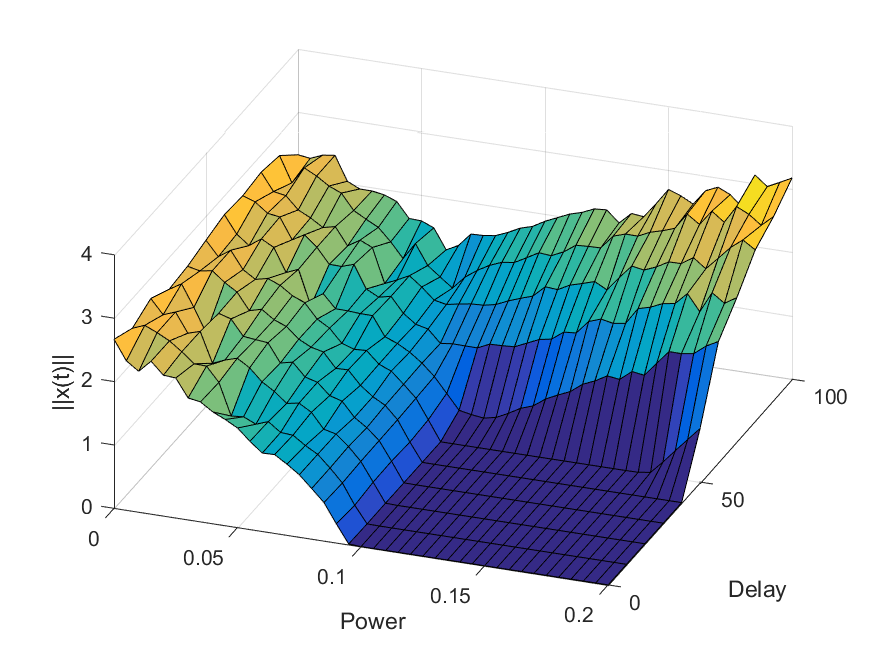

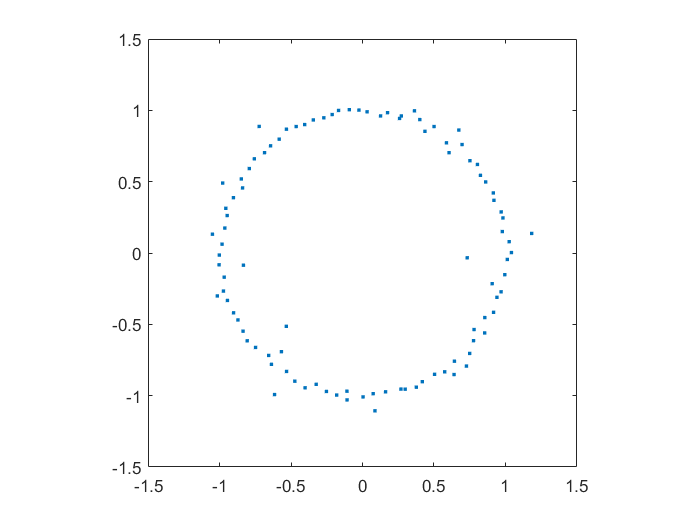

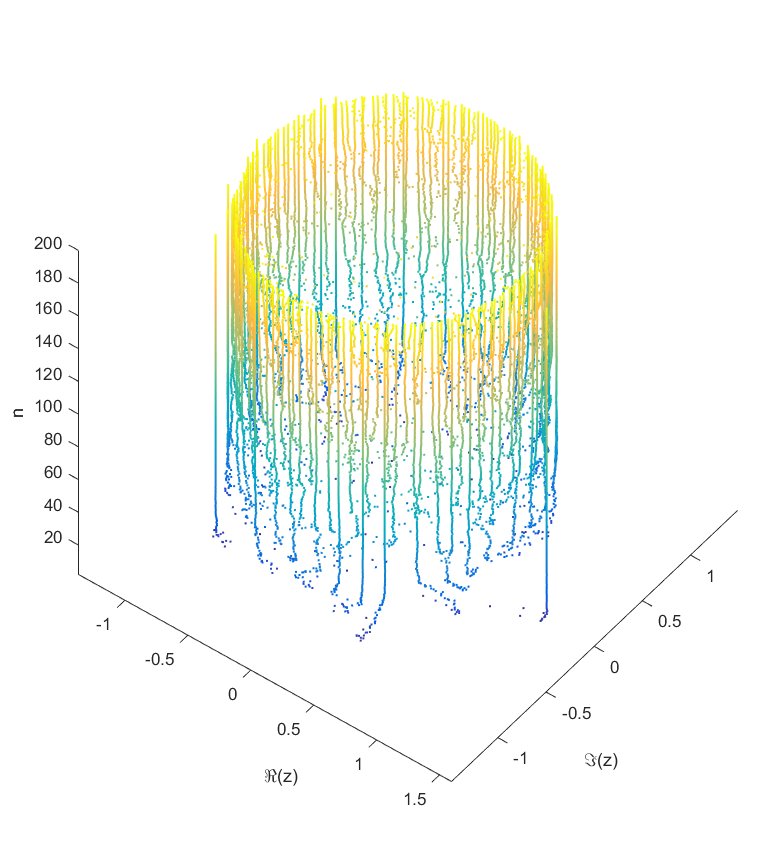

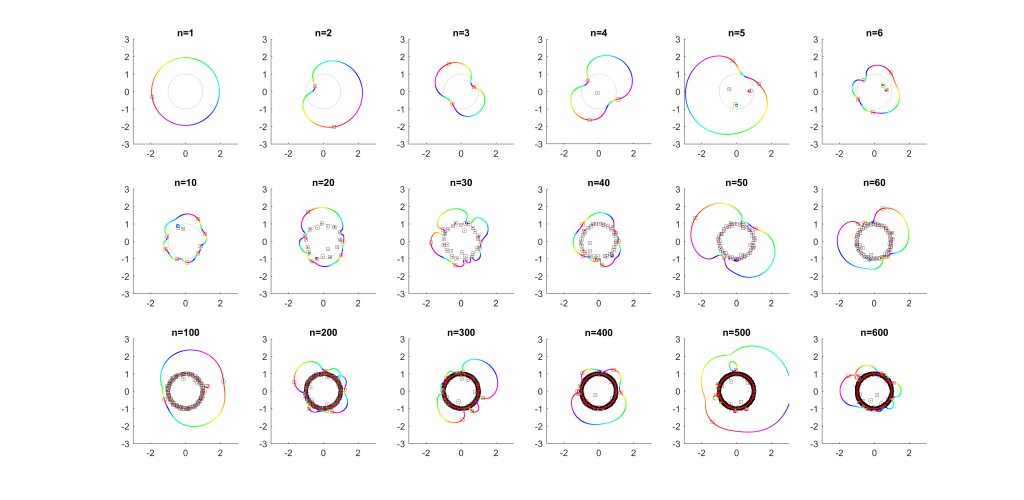

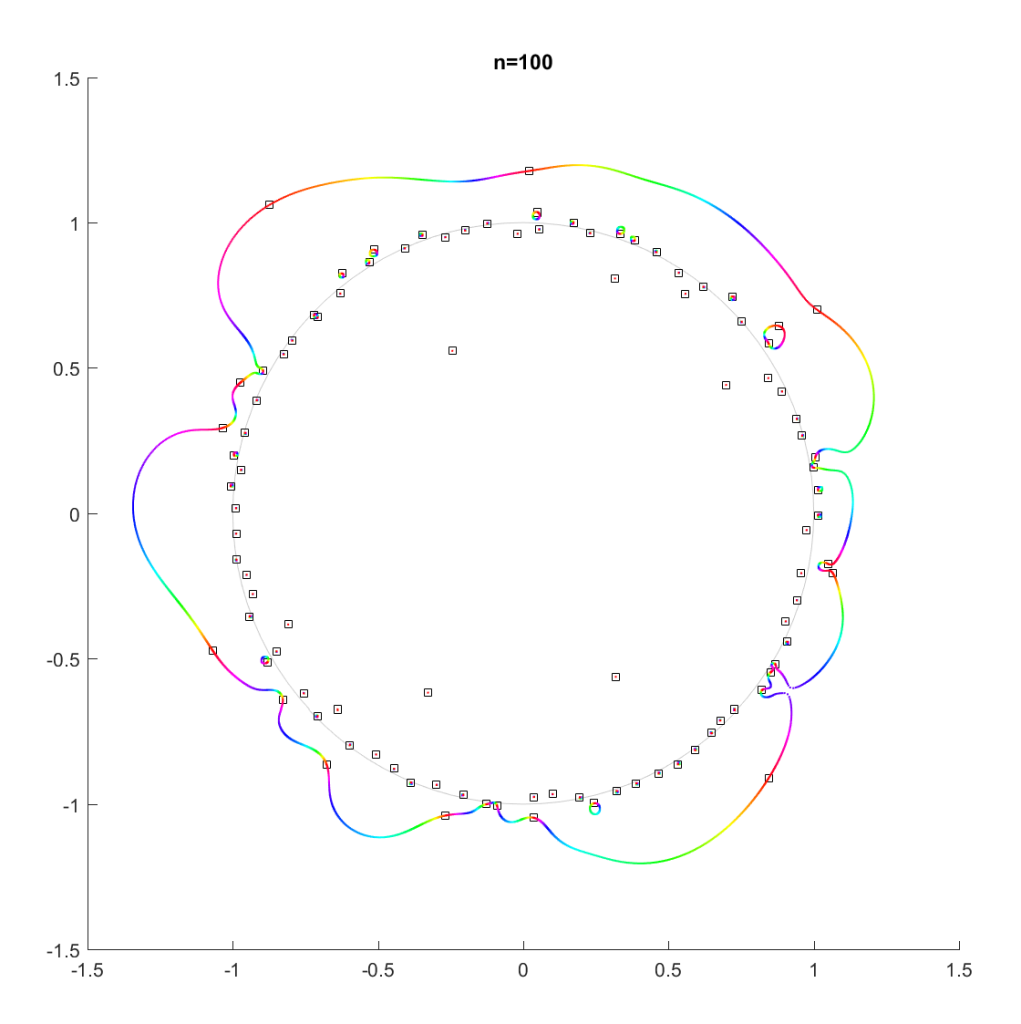

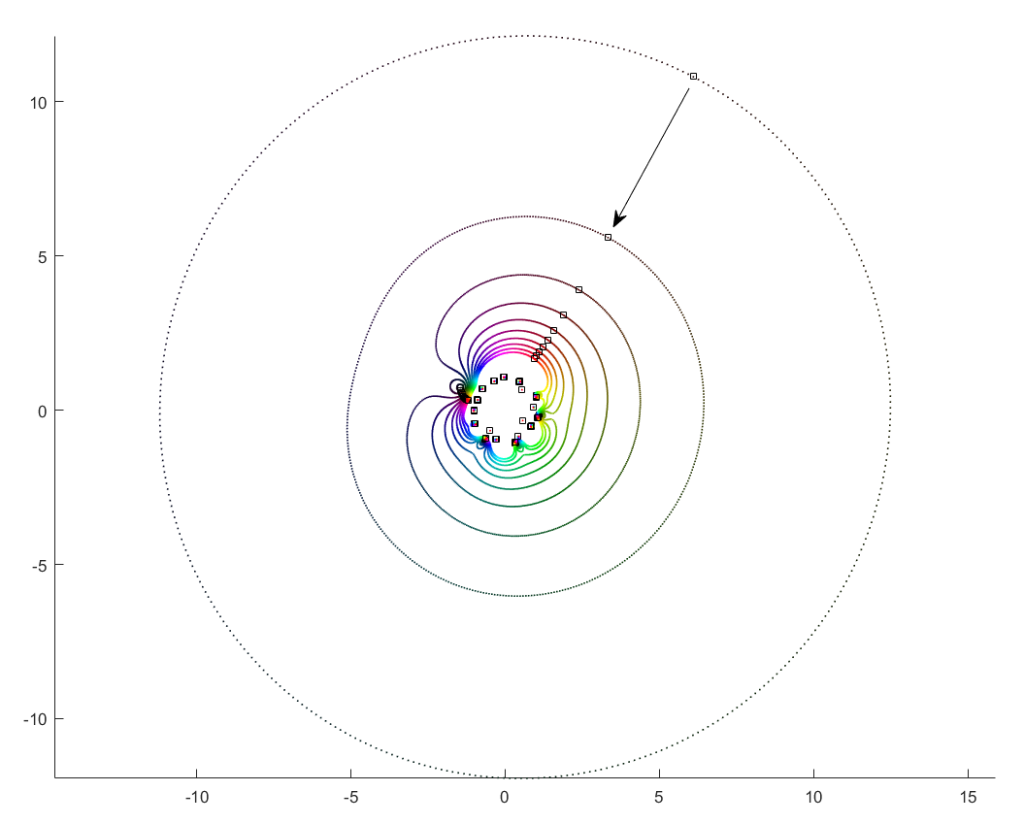

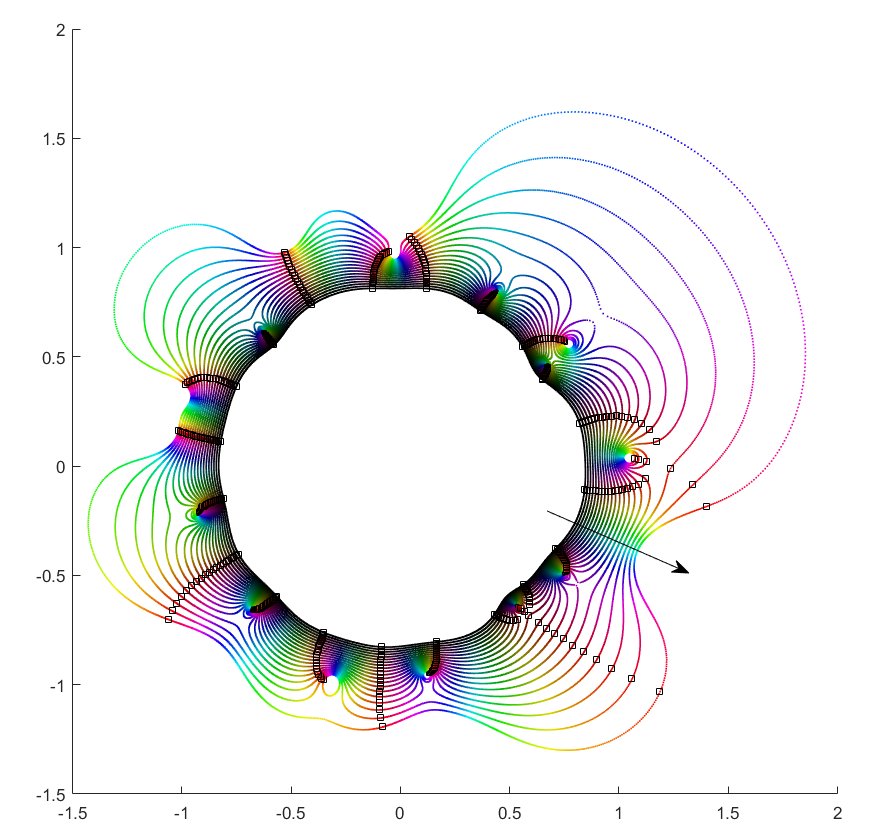

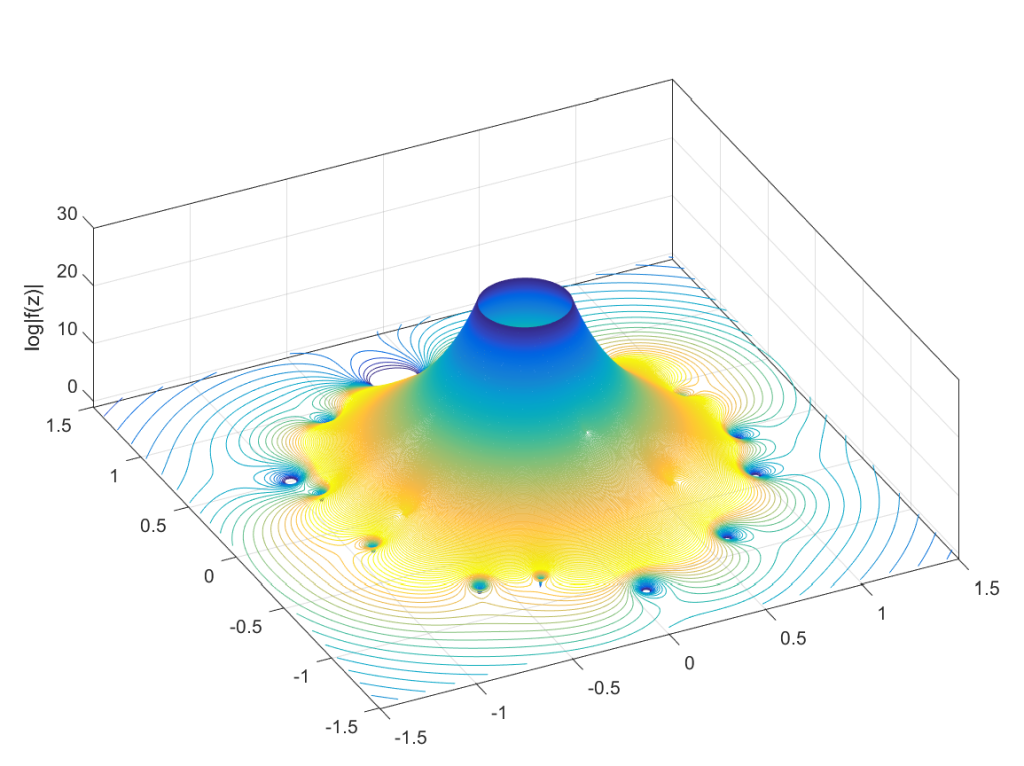

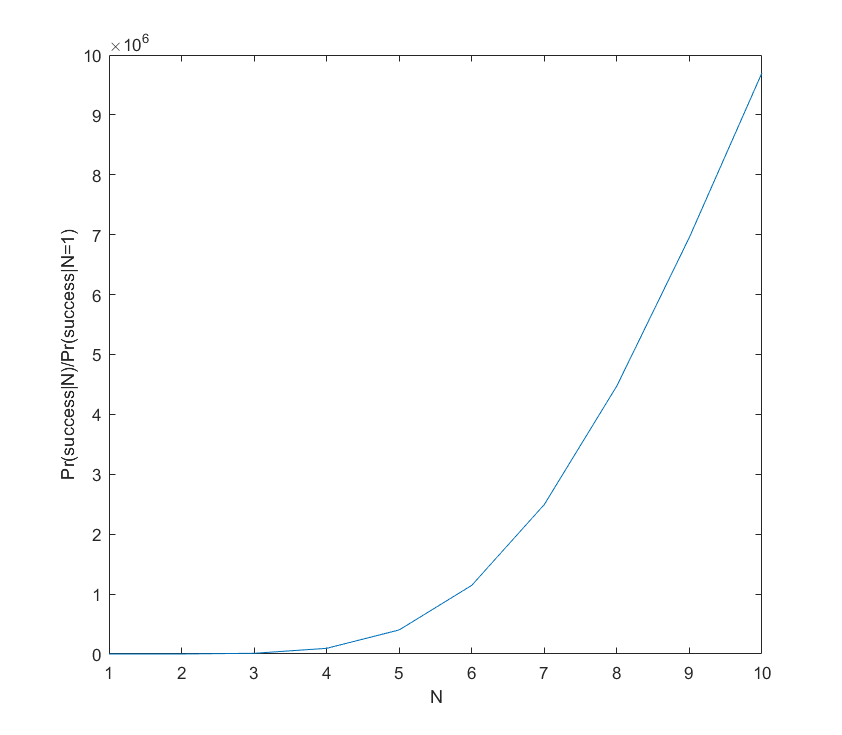

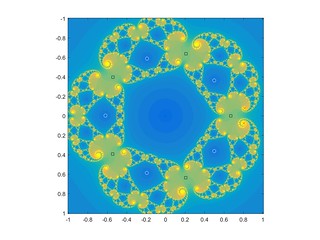

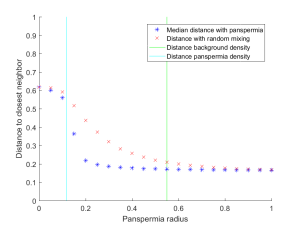

Running a Monte Carlo simulation shows this effect. Here I use 10,000 possible life sites in a cubical volume, and – the number of panspermias will be Poisson(1) distributed. The background rate of civilizations appearing is 1/10,000, but in panspermias it is 1/100. As I make panspermias larger civilizations become more common and the median distance from a civilization to the next closest civilization falls (blue stars). If I re-sample so the number of civilizations are the same but their locations are uncorrelated I get the red crosses: the distances decline, but they can be more than a factor of 2 larger.

Technological correlations

The technological terms and

can also show spatial patterns, if civilizations spread out from their origin.

The basic colonization argument by Hart and Tipler assumes a civilization will quickly spread out to fill the galaxy; at this point if we count inhabited systems. If we include intergalactic colonization, then in due time, everything out to a radius of reachability on the order of 4 gigaparsec (for near c probes) and 1.24 gigaparsec (for 50% c probes). Within this domain it is plausible that the civilization could maintain whatever spatio-temporal correlations it wishes, from perfect homogeneity over the zoo hypothesis to arbitrary complexity. However, the reachability limit is due to physics and do impose a pretty powerful limit: any correlation in the Drake equation due to a cause at some point in space-time will be smaller than the reachability horizon (as measured in comoving coordinates) for that point.

Total colonization is still compatible with an empty galaxy if is short enough. Galaxies could be dominated by a sequence of “empires” that disappear after some time, and if the product between empire emergence rate

and

is small enough most eras will be empty.

A related model is Brin’s resource exhaustion model, where civilizations spread at some velocity but also deplete their environment at some (random rate). The result is a spreading shell with an empty interior. This has some similarities to Hanson’s “burning the cosmic commons scenario”, although Brin is mostly thinking in terms of planetary ecology and Hanson in terms of any available resources: the Hanson scenario may be a single-shot situation. In Brin’s model “nursery worlds” eventually recover and may produce another wave. The width of the wave is proportional to where

is the expansion speed; if there is a recovery parameter

corresponding to the time before new waves can emerge we should hence expect spatial correlation length of order

. For light-speed expansion and a megayear recovery (typical ecology and fast evolutionary timescale) we would get a length of a million light-years.

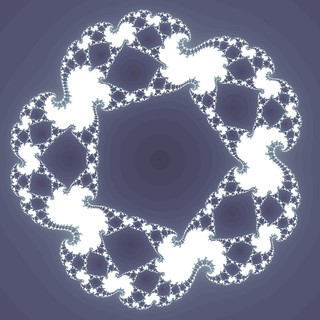

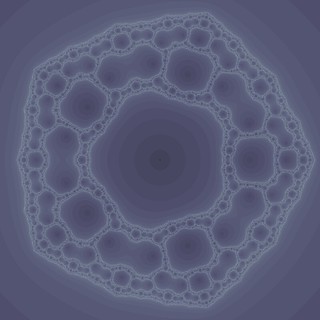

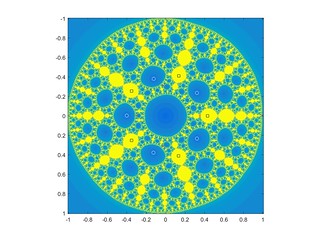

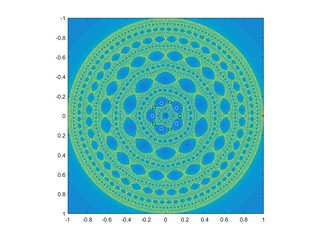

Another approach is the percolation theory inspired models first originated by Landis. Here civilizations spread short distances, and “barren” offshoots that do not colonize form a random “bark” around the network of colonization (or civilizations are limited to flights shorter than some distance). If the percolation parameter is low, civilizations will only spread to a small nearby region. When it increases larger and larger networks are colonized (forming a fractal structure), until a critical parameter value

where the network explodes and reaches nearly anywhere. However, even above this transition there are voids of uncolonized worlds. The correlation length famously scales as

, where

for this case. The probability of a random site belonging to the infinite cluster for

scales as

(

) and the mean cluster size (excluding the infinite cluster) scales as

(

).

So in this group of models, if the probability of a site producing a civilization is the probability of encountering another civilization in one’s cluster is

for . Above the threshold it is essentially 1; there is a small probability

of being inside a small cluster, but it tends to be minuscule. Given the silence in the sky, were a percolation model the situation we should conclude either an extremely low

or a low

.

Temporal correlations

Another way the Drake equation can become misleading is if the parameters are time varying. Most obviously, the star formation rate has changed over time. The metallicity of stars have changed, and we should expect any galactic life zones to shift due to this.

One interesting model due to James Annis and Milan Cirkovic is that the rate of gamma ray bursts and other energetic disasters made complex life unlikely in the past, but now the rate has declined enough that it can start the climb towards intelligence – and it was synchronized by this shared background. Such disasters can also produce spatial coherency, although it is very noisy.

In my opinion the most important temporal issue is inherent in the Drake equation itself. It assumes a steady state! At the left we get new stars arriving at a rate , and at the right the rate gets multiplied by the longevity term for civilizations

, producing a dimensionless number. Technically we can plug in a trillion years for the longevity term and get something that looks like a real estimate of a teeming galaxy, but this actually breaks the model assumptions. If civilizations survived for trillions of years, the number of civilizations would currently be increasing linearly (from zero at the time of the formation of the galaxy) – none would have gone extinct yet. Hence we can know that in order to use the unmodified Drake equation

has to be

years.

Making a temporal Drake equation is not impossible. A simple variant would be something like

where the first term is just the factors of the vanilla equation regarded as time-varying functions and the second term a decay corresponding to civilizations dropping out at a rate of 1/L (this assumes exponentially distributed survival, a potentially doubtful assumption). The steady state corresponds to the standard Drake level, and is approached with a time constant of 1/L. One nice thing with this equation is that given a particular civilization birth rate corresponding to the first term, we get an expression for the current state:

.

Note how any spike in gets smoothed by the exponential, which sets the temporal correlation length.

If we want to do things even more carefully, we can have several coupled equations corresponding to star formation, planet formation, life formation, biosphere survival, and intelligence emergence. However, at this point we will likely want to make a proper “demographic” model that assumes stars, biospheres and civilization have particular lifetimes rather than random disappearance. At this point it becomes possible to include civilizations with different L, like Sagan’s proposal that the majority of civilizations have short L but some have very long futures.

The overall effect is still a set of correlation timescales set by astrophysics (star and planet formation rates), biology (life emergence and evolution timescales, possibly the appearance of panspermias), and civilization timescales (emergence, spread and decay). The overall effect is dominated by the slowest timescale (presumably star formation or very long-lasting civilizations).

Conclusions

Overall, the independence of the terms of the Drake equation is likely fairly strong. However, there are relevant size scales to consider.

- Over multiple gigaparsec scales there can not be any correlations, not even artificially induced ones, because of limitations due to the expansion of the universe (unless there are super-early or FTL civilizations).

- Over hundreds of megaparsec scales the universe is fairly uniform, so any natural influences will be randomized beyond this scale.

- Colonization waves in Brin’s model could have scales on the galactic cluster scale, but this is somewhat parameter dependent.

- The nearest civilization can be expected around

, where

is the galactic volume. If we are considering parameters such that the number of civilizations per galaxy are low V needs to be increased and the density will go down significantly (by a factor of about 100), leading to a modest jump in expected distance.

- Panspermias, if they exist, will have an upper extent limited by escape from galaxies – they will tend to have galactic scales or smaller. The same is true for galactic habitable zones if they exist. Percolation colonization models are limited to galaxies (or even dense parts of galaxies) and would hence have scales in the kiloparsec range.

- “Scars” due to gamma ray bursts and other energetic events are below kiloparsecs.

- The lower limit of panspermias are due to

being smaller than the panspermia, presumably at least in the parsec range. This is also the scale of close clusters of stars in percolation models.

- Time-wise, the temporal correlation length is likely on the gigayear timescale, dominated by stellar processes or advanced civilization survival. The exception may be colonization waves modifying conditions radically.

In the end, none of these factors appear to cause massive correlations in the Drake equation. Personally, I would guess the most likely cause of an observed strong correlation between different terms would be artificial: a space-faring civilization changing the universe in some way (seeding life, wiping out competitors, converting it to something better…)