By Anders Sandberg, Future of Humanity Institute, Oxford Martin School, University of Oxford

Thinking of the future is often done as entertainment. A surprising number of serious-sounding predictions, claims and prophecies are made with apparently little interest in taking them seriously, as evidenced by how little they actually change behaviour or how rarely originators are held responsible for bad predictions. Rather, they are stories about our present moods and interests projected onto the screen of the future. Yet the future matters immensely: it is where we are going to spend the rest of our lives. As well as where all future generations will live – unless something goes badly wrong.

Thinking of the future is often done as entertainment. A surprising number of serious-sounding predictions, claims and prophecies are made with apparently little interest in taking them seriously, as evidenced by how little they actually change behaviour or how rarely originators are held responsible for bad predictions. Rather, they are stories about our present moods and interests projected onto the screen of the future. Yet the future matters immensely: it is where we are going to spend the rest of our lives. As well as where all future generations will live – unless something goes badly wrong.

Olle Häggström’s book is very much a plea for taking the future seriously, and especially for taking exploring the future seriously. As he notes, there are good reasons to believe that many technologies under development will have enormous positive effects… and also good reasons to suspect that some of them will be tremendously risky. It makes sense to think about how we ought to go about avoiding the risks while still reaching the promise.

Current research policy is often directed mostly towards high quality research rather than research likely to make a great difference in the long run. Short term impact may be rewarded, but often naively: when UK research funding agencies introduced impact evaluation a few years back, their representatives visiting Oxford did not respond to the question on whether impact had to be positive. Yet, as Häggström argues, obviously the positive or negative impact of research must matter! A high quality investigation into improved doomsday weapons should not be pursued. Investigating the positive or negative implications of future research and technology has high value, even if it is difficult and uncertain.

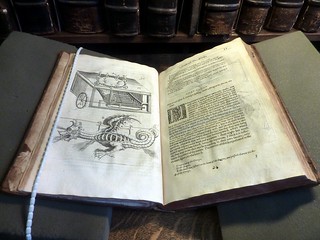

Inspired by James Martin’s The Meaning of the 21st Century this book is an attempt to make a broad map sketch of parts of the future that matters, especially the uncertain corners where we have reason to think dangerous dragons lurk. It aims more at scope than the detail of many of the covered topics, making it an excellent introduction and pointer towards the primary research.

One obvious area is climate change, not just in terms of its direct (and widely recognized risks) but the new challenges posed by geoengineering. Geoengineering may both be tempting to some nations and possible to perform unilaterally, yet there are a host of ethical, political, environmental and technical risks linked to it. It also touches on how far outside the box we should search for solutions: to many geoengineering is already too far, but other proposals such as human engineering (making us more eco-friendly) go much further. When dealing with important challenges, how do we allocate our intellectual resources?

Other areas Häggström reviews include human enhancement, artificial intelligence, and nanotechnology. In each of these areas tremendously promising possibilities – that would merit a strong research push towards them – are intermixed with different kinds of serious risks. But the real challenge may be that we do not yet have the epistemic tools to analyse these risks well. Many debates in these areas contain otherwise very intelligent and knowledgeable people making overconfident and demonstrably erroneous claims. One can also argue that it is not possible to scientifically investigate future technology. Häggström disagrees with this: one can analyse it based on currently known facts and using careful probabilistic reasoning to handle the uncertainty. That results are uncertain does not mean they are useless for making decisions.

He demonstrates this by analysing existential risks, scenarios for the long term future humanity and what the “Fermi paradox” may tell us about our chances. There is an interesting interplay between uncertainty and existential risk. Since our species can end only once, traditional frequentist approaches run into trouble Bayesian methods do not. Yet reasoning about events that are unprecedented also makes our arguments terribly sensitive to prior assumptions, and many forms of argument are more fragile than they first look. Intellectual humility is necessary for thinking about audacious things.

In the end, this book is as much a map of relevant areas of philosophy and mathematics containing tools for exploring the future, as it is a direct map of future technologies. One can read it purely as an attempt to sketch where there may be dragons in the future landscape, but also as an attempt at explaining how to go about sketching the landscape. If more people were to attempt that, I am confident that we would fence in the dragons better and direct our policies towards more dragon-free regions. That is a possibility worth taking very seriously.

[Conflict of interest: several of my papers are discussed in the book, both critically and positively.]