Looking back at 2025 and forward to 2026, here are some notes.

Changed mind about

The thing I changed my mind most about in 2025 was group agency and other collective properties. I have long declared myself an methodological individualist in social science, and I still think that group properties supervene on individuals. That groups can have knowledge not found in the members, or collectively be able to perform things individuals cannot, was not too problematic. There is distributed knowledge embodied in a market. But being a Hayekian does not mean one need to go much further. Or does it?

My work on exoselves made me happy to think about extended minds. Seeing markets, wikis, my own files, and surrounding organisations are part of an extended self or an extended mind… OK.

Then I wrote a paper about civilizational virtue, arguing that it does indeed make sense to say that all of humanity can exhibit certain virtues that individuals simply cannot have. Maybe it is not right now virtue-apt or agency-apt, but that could change. At least environmental virtues seem much more reasonable as group virtues than individual virtues.

Much of the year I have been working on the book Liberty, Law, Leviathan. We argue that much of society can be seen as collective cognition. Institutions on all scales are mechanisms achiving useful coordination, but also embodying knowledge in collective cognitive structures. These structures are not wholly human – right now much is also on pieces of paper and databases, but increasingly there will be AI components. As we argue, these non-human components are likely to slowly become dominant.

Anyway, this is the point where I look back and realize that those groups of people (and AIs) seem to have a lot of agency, knowledge, and other ethically relevant properties. Maybe we can say they supervene on individuals organised in the right way, but things look pretty emergent. And given that I am roughly a functionalist when it comes to minds, maybe I should not be too surprised: parts can come together to make interesting and important emergent systems. Still, it was an update.

Another fun update was space data centers. I started the year thinking this was a stupid idea, pointing at the overly optimistic thermal estimates in the whitepaper from a Y Combinator company. Obvious nonsense… but then more and more people I respect started to change views, more and more companies began to look into it. I realized that the technical stuff (heat, radiation, launching, etc.) is just technical challenges, not fundamental limits, and we have long experience of people solving problems like that. I still am not holding my breath about the economics, but I think people dismissing the idea due to an obvious issue are like the overconfident astronomers dismissing spaceflight due to obvious flaws in their bad mental models of what rockets would do.

AI timelines and P(doom)

I am still pretty optimistic about the feasibility of alignment, at least to the first order. Getting AI that is safe enough for everyday work looks possible to me. Whether we can get the second order alignment needed to prevent emergent global misbehavior, the wrong kind of gradual disempowerment, or just loss of the niches where humans can flourish remains to be seen. I am optimistic there too, but it does not count for much.

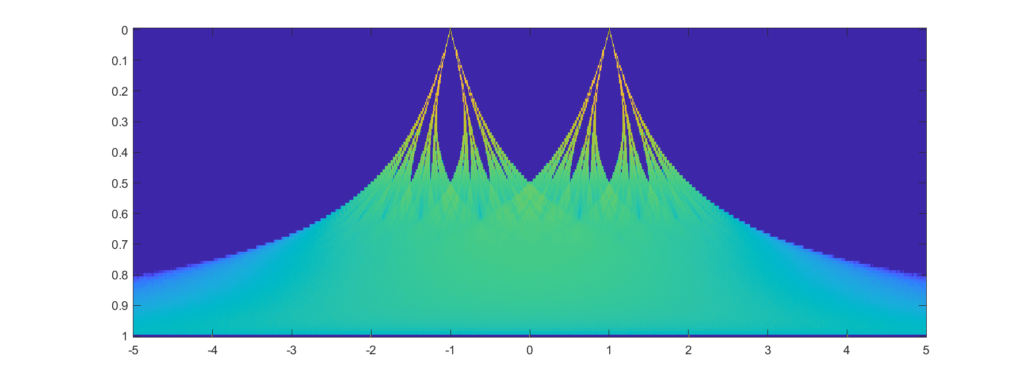

That does not mean I am feeling calm. Quite the opposite. I think we passed the event horizon in 2025.

My own AGI timelines are longer than most in my environment, but (1) AI is now useful enough to really start mattering economically and scientifically (it will become transformative enough to cause big turbulence before long), (2) the forces that could have shaped or regulated it rationally now appear too weak to do it, and (3) the pull of building, using and legislating for more AI is growing rapidly.

When you approach a black hole the event horizon is not special: spacetime there looks similar to elsewhere. But if you cross, you have only paths leading to the singularity ahead of you, even if you try to steer. (It was professor Shivaji Sondhi in Physics who first used this metaphor in my circles; Toby Ord pointed out that maybe it is a bit more like crossing the Innermost Stable Circular Orbit (ISCO): one is not trapped yet, but at this point there are no unpowered trajectories that will not end up inside, and escapes will require a deliberate effort).

This is not just a US thing, but one could argue that it is enough for one solid part of the world to pass the event horizon to make the rest of the world have to follow it (or be reduced to irrelevance).

This was the year when LLMs went from funny things to write roleplaying game text with to research assistants that actually help me academically. Mostly the scurrying down the stacks to explore topics and bringing back finds. I had at least two moments where the LLM impressed me deeply: one by suggesting that I had not explored a particular topic in enhancement ethics and suggesting a really good paper idea, one where it found that The Big Conclusion had a really interesting interaction with Confucian thinking that I would never have considered on my own. There are several more cases where I think one should describe it as having valid and good “insights”. And I have not yet even tried Claude Code…

Hence my prediction is that 2026 will see an amplification of early adopter ability to do stuff that will be quite breathtaking. Meanwhile the AI Cope Bubble and the AI Stock Bubble may well burst. This can give rise to two kinds of panic: incumbents and many others feeling very, very threatened by the changes and demand strong action, and a big economic kaboom that I leave to more financially astute people to pontificate about. Bubbles can persist longer than any reasonable prediction allows for, so don’t bet on either bursting. If I am right about the event horizon dynamics this will not change the move towards even more AI but there will be tremendous turbulence around it. Having empowered early adopter individuals and organisations, incumbents fighting for their positions using all available social capital, and many people getting a rude awakening that the world is getting weirder faster than expected. Think how the cryptocurrencies gave technophiles, libertarians, and criminals significant resources (making the world way weirder), but on a larger scale.

This is why I think the P(doom) is not straightforwardly just due to risk from misaligned AI: the bulk of the risk is from human society shaking apart due to massive empowerment combined with new dangerous self-replicating technologies. There is also a big gradual disempowerment part where we end up with fairly individually aligned AI but do not gain enough coordination ability to prevent emergent misbehaviour from claiming us. Third place, human-AI alignment where we end up aligned to some AI values, an outcome that ranges from existentially bad to weirdly meh. I still give P(doom) 10%, but I think there is a big penumbra of bad futures. After all, an automated totalitarian state that prevents rebellion well enough to be the universal attractor is not an AI existential risk, but pretty doomy. We need to work hard on these risks, but the challenge is not just to the AI alignment programmers but to the economists, diplomats and institution-builders!

If there is a AI bubble burst there might also be plenty of hand-me-down datacenters we in the brain emulation community can find good uses for. Indeed, I have come to believe that the way of getting WBE to work will be synergistic with AI. We do not need AGI to solve WBE, just automated research to help close the fixate – scan – interpet – model – test loop. That will get easier and easier the better the AI is, and hence I expect WBE to arrive not later than AGI but earlier – perhaps by a lot, perhaps almost simultaneously. And the neurotech people are doing amazing things already!

Conclusion

There is no particular conclusion. I don’t have the time, there is too much to do.

And yes, I am working on Grand Futures!

Footnote 1

I am one of the longer AGI timeline people in my circles, mostly because I do think LLMs are not good enough to do full general problem-solving… but they fake it effectively. As the scaffolding and reinforcement-learning help this solving get longer the “cheap intelligence” gets better, which has real practical effects. But it is not open-ended in a cheap way (scaling laws and reinforcement learning are expensive in terms of compute!) I expect the breakthrough to be due to some algorithmic or architectural change. Which does not give me confidence in any prediction – it might be a small extra thing, or a really non-trivial insight. This makes my timelines stretch longer into the future.