Today I handed in my laptop. A part of my extended mind was removed. The shutdown of the Future of Humanity Institute has many odd effects.

Today I handed in my laptop. A part of my extended mind was removed. The shutdown of the Future of Humanity Institute has many odd effects.

I have been at FHI since 2006. I interviewed for the job a rainy July day in 2005, apparently impressing people with my interdisciplinary knowledge… and the fact that I could do web design (unheard of in the Oxford philosophy faculty at the time). I moved to Oxford in the chill of January 2006, becoming a part of the university. I soon realized that this was my kind of place, and that I wanted to stay once the project ended. It ended up being 19 years so far, but on a blustery spring day in 2024 the Institute ended.

I have written a history/memorial about the FHI elsewhere. This post is about some other thoughts that didn’t fit in, or I thought about later.

Substance and play

Why did I latch on to FHI so tightly? Obviously, Oxford is a nice (and prestigious) place to live and work. It is a great intellectual milieu and a practical home base. But there are others places like that. What really caught me was the combination of intellectual substance and play.

Why did I latch on to FHI so tightly? Obviously, Oxford is a nice (and prestigious) place to live and work. It is a great intellectual milieu and a practical home base. But there are others places like that. What really caught me was the combination of intellectual substance and play.

FHI aimed at working on the biggest questions about humanity’s long-term prospects, the questions where answers would have the most impact for improving our future. This includes deep philosophical questions about what actually matters, how to think rigorously about these things, and how to set priorities. It also includes the investigation of emerging technology, natural and technological hazards, as well as digging into useful facts from all sorts of disciplines. This is of course delightful for a magpie generalist like me, but it also offered the opportunity to work on synthesis. The questions we pursued were weighty and we were motivated to actually try to make practical progress on them. Compare that to being part of a fashionable field where it is more important to quickly claim interesting results than to make sure the results can be used to build the understanding more deeply.

That said, I do not claim we consistently got the deepest substance. Often, we just marked a likely mining spot after having broken our tools on the hard rock and we moved on. On the other hand, we also had tremendous intellectual play. Some was just frivolous like us developing a theory of what equations written on a pane of glass remained true when viewed from the other side, or my blueberry earth paper. Others were experimentation with methodologies, checking out remote disciplines to see if they had anything to offer. There was a definite joy in learning new things from each other and from the world.

One of the defining parts of FHI culture was earnestness: we did not pretend to be interested in things we were not interested in, nor did we pretend disinterest in our latest obsessions. Sometimes we were mystified why others did not share our views, but we also recognized each other’s independence.

If you find a place of substance and play, stay there.

Whiteboards

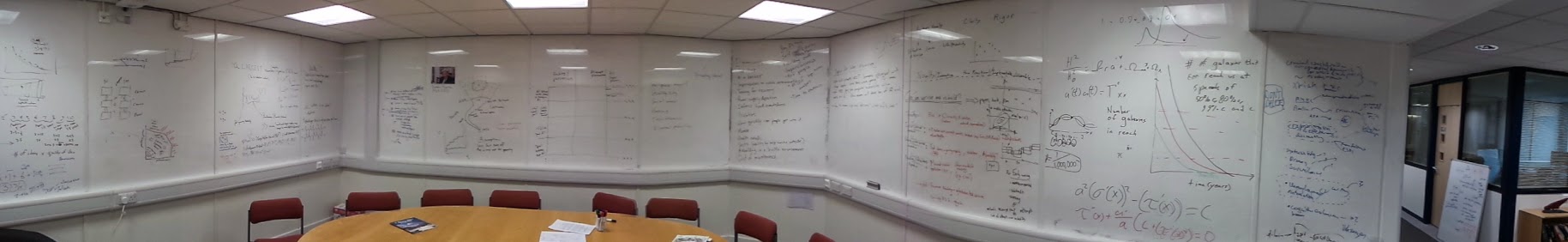

Looking at the photos of FHI history there is one character that stands out: the whiteboard. The FHI whiteboard was in a way a quiet but important team member. Whiteboards are not just means of presentation but an extension of working memory. A collective extension: I often became aware of some new development by seeing it show up among the scribbles on the main whiteboard. It represented the joint state of what the institute was thinking about.

I think this is an important function at any cognitive organization. We need coordination and information sharing, but explicit methods (meetings, emails, memos, slack) take time and interrupt the natural workflow. Whiteboards provide a “quiet” way of establishing a sense of what is going on.

The placement and size of whiteboards matter. They need to be large enough to contain complex detailed diagrams, quick sketches, calculations, and ideally several meetings worth of them. Small whiteboards get erased too often, and constrain their use cases.

Whiteboards in offices act as person-linked publicly visible working memories: valuable, but much less collaboration-enhancing than public whiteboards. Working on a public whiteboard is an invitation for collaboration. I often found that a quick inspiration leading to a test calculation or diagram led to others getting involved in informal discussion, sometimes turning into a more long-running collaboration. If nothing else, it provided quick critique and reviews.

I am a believer in the extended mind hypothesis. Those whiteboards were part not just of my mind, but all our minds, linking us into a collective mind.

When we moved downstairs in Littlegate House from our first offices, I insisted that there must be more whiteboards (the whiteboard wall had been good, but had problems). Eventually I was brought down to see the result: a breathtaking 200-degree panorama! I fell in love with the James Martin Room, and I was delighted to pose for a portrait in my natural environment photographed by David Vintiner.

What was the value of FHI?

I don’t think this can be evaluated yet. It often takes time to get a perspective on what ideas become seeds of useful research and action, and for anything with more than entirely straightforward effects one can debate what kind of value it has endlessly and along new dimensions (French Revolution: too early to tell. Black death: net good or bad? What about the Bronze Age Collapse?).

I think one easily overlooked aspect of FHI was how it acted as a meeting point for people, creating communities of different kinds by placing people near each other. Newcomers learning about ideas, folk knowledge and problems, staff acting as local memory, and networking all around. This is of course what Oxford is doing in the large too. Here it was focused on the future and forming particular communities. Organizations are often started to do some particular tasks, but become important because they are meeting places.

After the news of the closure began to spread, we were contacted by many people. It was not just moving because of their concern and sorrow, but also because of the range of who they were. FHI was not just an academic research organization or a place where young future-oriented people developed, but also inspired many people outside academia. Even if we often had disquieting things to say, the possibility that it might be possible to think well about the future and make some positive change to it was something many loved. We need to think we can act in the world with hope and some direction, and institutions able to provide this need are important.

I have reached the age when I have seen a few lifecycles of organizations and movements I have followed. One lesson is that they don’t last: even successful movements have their moment and then become something else, sclerotize into something stable but useless, or peter out. This is fine. Not in some fatalistic “death is natural” sense, but in the sense that social organizations are dynamic, ideas evolve, and there is an ecological succession of things. 1990s transhumanism begat rationalism that begat effective altruism, and to a large degree the later movements suck up many people who would otherwise have been recruited by the transhumanists.

I have reached the age when I have seen a few lifecycles of organizations and movements I have followed. One lesson is that they don’t last: even successful movements have their moment and then become something else, sclerotize into something stable but useless, or peter out. This is fine. Not in some fatalistic “death is natural” sense, but in the sense that social organizations are dynamic, ideas evolve, and there is an ecological succession of things. 1990s transhumanism begat rationalism that begat effective altruism, and to a large degree the later movements suck up many people who would otherwise have been recruited by the transhumanists.

FHI did close before its time, but it is nice to know it did not become something pointlessly self-perpetuating. As we noted when summing up, 19 years is not bad for a 3-year project. Indeed, a friend remarked that maybe all organisations should have a 20-year time limit. After that, they need to be closed down and recreated if they are still useful, shedding some of the accumulated dross.

The ecological succession of organizations and movements is not all driven by good forces. A fresh structure driven by interested and motivated people is often gradually invaded by poseurs, parasites and imitators, gradually pushing away the original people (or worse, they mutate into curators, gatekeepers and administrators). Many ideas develop, flourish, become explored and then forgotten once a hype peak is passed – even if they still have merit. People burn out, lose interest, form families and have to change priorities, or the surrounding context make the movement change in nature. Dwindling activist movements may suffer “core collapse” as moderate members drift off while the hard core get more radical and pursue ever more extreme activism in order to impress each other rather than the world outside.

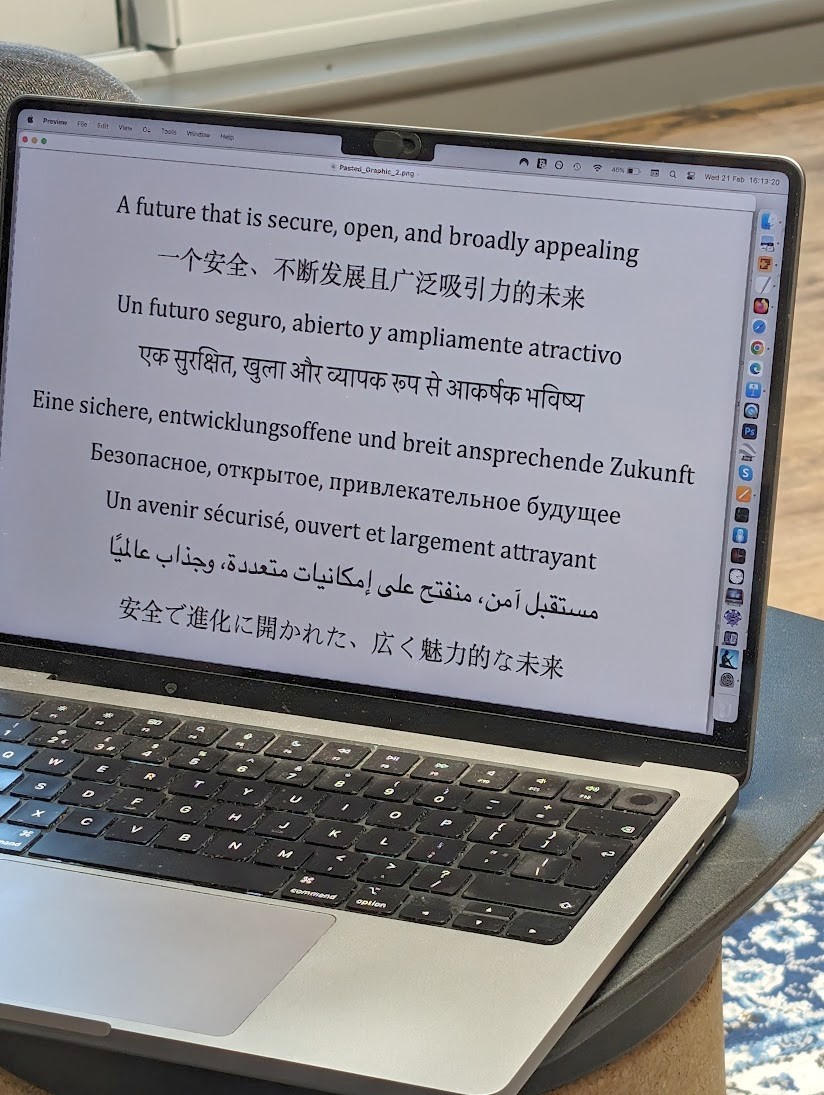

FHI did not do any of that. If we had a memetic failure, it was likely more along the lines of developing a shared model of the world and future that may have been in need for more constant challenge. That is one reason why I hope there will be more organizations like FHI but not thinking alike – places like CSER, Mimir, FLI, SERI, GCRI, and many others. We need the focus of a strongly connected organization to build thoughts and systems of substance but separate organizations to get mutual critique and diversity in approaches. Plus, hopefully, metapopulation resilience against individual organizational failures.

FHI also had a fairly high throughput of members due to shorter contracts, which was not great career-wise (and really bit us once we could not hire) but also kept away opportunism while favoring people who wanted to do what we did more than anything else.

Why did FHI get closed down? In the end, because it did not fit in with the surrounding administrative culture. I often described Oxford like a coral reef of calcified institutions built on top of each other, a hard structure that had emerged organically and haphazardly and hence had many little nooks and crannies where colorful fish could hide and thrive. FHI was one such fish but grew too big for its hole. At that point it became either vulnerable to predators, or had to enlarge the hole, upsetting the neighbors. When an organization grows in size or influence, it needs to scale in the right way to function well internally – but it also needs to scale its relationships to the environment to match what it is.

How do I feel?

Sending out a “my email has changed” email to the literally thousands of contacts one has produces an effect akin to a premature obituary, but much nicer.

One of the most moving things over the past few days has been all the emails from concerned colleagues, friends, and remote acquaintances. Thank you! It has been hard to keep up, but it has also been therapeutic to know that I am surrounded by a vast network of friendly minds.

I would particularly like to mention my students at Reuben College. They have been amazingly supportive, which makes me think I somehow has done something right.

I am not leaving Oxford, it is a lovely place to live and an excellent home base with many friends. But I am also going to be working more at the Institute for Futures Studies in Stockholm – another home base, where I hope the Mimir Centre for Long Term Futures can become something akin to FHI for all of northern Europe.

Am I staying in academia? IFFS is certainly academic, but not part of a university. Indeed, these days there are more and more forms of research not happening at traditional universities. There are research startups, focused research organizations, think tanks, ARPAs and much else. While I do love the pomp and circumstance of University of Oxford (I love wearing formal gowns) and it has plenty of excellent research, it is not entirely clear that modern academia is optimal for the research I want to do. Much has been written about how the incentives are biasing towards the wrong kind of research, all the misfeatures of the evaluation systems (whether peer review or citation counts), and of course the political and cultural biases that determine what is being researched.

When I became 25, I had a brief quarter century crisis: what had I done with my life? Five seconds of thought made me see that I had mostly been learning stuff. I resolved to spend the next 25 years using it. I did (and kept on learning more). When I turned 50 I repeated the mini-crisis: what now? I realized that I had not been steering particularly intentionally – I had taken opportunities as they arose, but not really created my own opportunities. I think now is the time do so.

But tomorrow I will take a long walk, enjoying the spring flowers.