By Stuart Armstrong

Introduction

I’ve been looking to develop a system of time travel in which it’s possible to actually have a proper time war. To make it consistent and interesting, I’ve listed some requirements here. I think I have a fun system that obeys them all.

Time travel/time war requirement:

- It’s possible to change the past (and the future). These changes don’t just vanish.

- It’s useful to travel both forwards and backwards in time.

- You can’t win by just rushing back to the Big Bang, or to the end of the universe.

- There’s no “orthogonal time” that time travellers follow; I can’t be leaving 2015 to go to 1502 “while” you’re leaving 3015 to arrive at the same place.

- You can learn about the rules of time travel while doing it; however, time travel must be dangerous to the ignorant (and not just because machines could blow up, or locals could kill you).

- No restrictions that make no physical sense, or that could be got round by a human or a robot with half a brain. Eg: “you can’t make a second time jump from the arrival point of a first.” However, a robot could build a second copy of a time machine and of itself, and that could then jump back; therefore that initial restriction doesn’t make any particular sense.

- Similarly, no restrictions that are unphysical or purely narrative.

- It must be useful to, for instance, leave arrays of computers calculating things for you then jumping to the end to get the answer.

- Ideally, there would be only one timeline. If there are parallel universes, they must be simply describable, and allow time-travellers to interact with each other in ways they would care about.

- A variety of different strategies must be possible for fighting the war.

Consistent time travel

Earlier, I listed some requirements for a system of time travel – mainly that it be both scientifically consistent and open to interesting conflicts that aren’t trivially one-sided. Here is my proposal for such a thing, within the general relativity format.

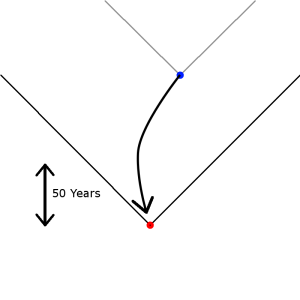

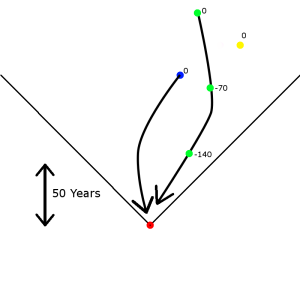

So, suppose you build a time machine, and want to go back in time to kill Hitler, as one does. Your time machine is a 10m diameter sphere, which exchanges place with a similarly-size sphere in 1930. What happens then? The graph here shows the time jump, and the “light-cones” for the departure (blue) and arrival (red) points; under the normal rules of causality, the blue point can only affect things in the grey cone, the red point can only affect things in the black cone.

The basic idea is that when you do a time jump like this, then you “fix” your points of departure and arrival. Hence the blue and red points cannot be changed, and the universe rearranges itself to ensure this. The big bang itself is also a fixed point.

The basic idea is that when you do a time jump like this, then you “fix” your points of departure and arrival. Hence the blue and red points cannot be changed, and the universe rearranges itself to ensure this. The big bang itself is also a fixed point.

All this “fixed point” idea is connected to entropy. Basically, we feel that time advances in one direction rather than the other. Many have argued that this is because entropy (roughly, disorder) increases in one direction, and that this direction points from the past to the future. Since most laws of physics are symmetric in the past and the future, I prefer to think of this as “every law of physics is time-symmetric, but the big bang is a fixed point of low entropy, hence the entropy increase as we go away from it.”

But here I’m introducing two other fixed points. What will that do?

Well, initially, not much. You go back into time, and kill Hitler, and the second world war doesn’t happen (or maybe there’s a big war of most of Europe against the USSR, see configuration 2 in “A Landscape Theory of Aggregation”). Yay! That’s because, close to the red point, causality works pretty much as you’d expect.

However, close to the blue point, things are different.

Here, the universe starts to rearrange things so that the blue point is unchanged. Causality isn’t exactly going backwards, but it is being funnelled in a particular direction. People who descended from others who “should have died” in WW2 start suddenly dying off. Memories shift; records change. By the time you’re very close to the blue point, the world is essentially identical to what it would have been had there been no time travelling.

Does this mean that you time jump made no difference? Not at all. The blue fixed point only constrains what happens in the light cone behind it (hence the red-to-blue rectangle in the picture). Things outside the rectangle are unconstrained – in particular, the future of that rectangle. Now, close to the blue point, the events are “blue” (ie similar to the standard history), so the future of those events are also pretty blue (similar to what would have been without the time jump) – see the blue arrows. At the edge of the rectangle, however, the events are pretty red (the alternative timeline), so the future is also pretty red (ie changed) – see the red arrows. If the influence of the red areas converges back in to the centre, the future will be radically different.

(some people might wonder why there aren’t “changing arrows” extending form the rectangle into the past as well as the future. There might be, but remember we have a fixed point at the big bang, which reduces the impact of these backward changes – and the red point is also fixed, exerting a strong stabilising influence for events in its own backwards light-cone).

So by time travelling, you can change the past, and you can change part of the future – but you can’t change the present.

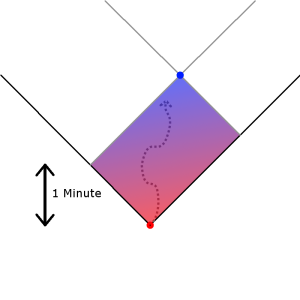

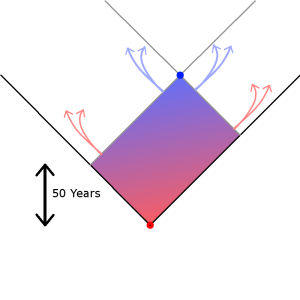

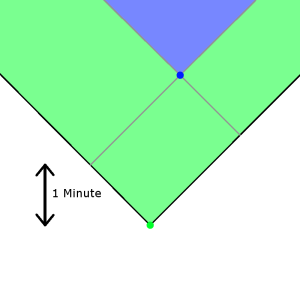

But what would happen if you stayed alive from 1930, waiting and witnessing history up to the blue point again? This would be very dangerous; to illustrate, let’s change the scale, and assume we’ve only jumped a few minutes into the past.

Maybe there you meet your past self, have a conversation about how wise you are, try and have sex with yourself, or whatever time travellers do with past copies of themselves. But this is highly dangerous! Within a few minutes, all trace of future you’s presesence will be gone; you past self will have no memory of it, there will be no physical or mental evidence remaining.

Maybe there you meet your past self, have a conversation about how wise you are, try and have sex with yourself, or whatever time travellers do with past copies of themselves. But this is highly dangerous! Within a few minutes, all trace of future you’s presesence will be gone; you past self will have no memory of it, there will be no physical or mental evidence remaining.

Obviously this is very dangerous for you! The easiest way for there to remain no evidence of you, is for there to be no you. You might say “but what if I do this, or try and do that, or…” But all your plans will fail. You are fighting against causality itself. As you get closer to the blue dot, it’s as if time itself was running backwards, erasing your new timeline, to restore the old one. Cleverness can’t protect you against an inversion of causality.

Your only real chance of survival (unless you do a second time jump to get out of there) is to rush away from the red point at near light-speed, getting yourself to the edge of the rectangle and ejecting yourself from the past of the blue point.

Right, that’s the basic idea!

Multiple time travellers

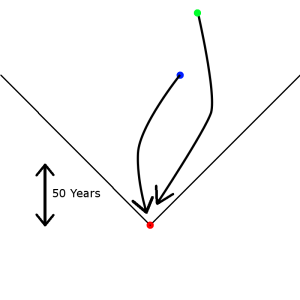

Ok, the previous section looked at a single time traveller. What happens when there are several? Say two time travellers (blue and green) are both trying to get to the red point (or places close to it). Who gets there “first”?

Here is where I define the second important concept for time-travel, that of “priority”. Quite simply, a point with higher priority is fixed relative to the other. For instance, imagine that the blue and green time travellers appear in close proximity to each other:

Here is where I define the second important concept for time-travel, that of “priority”. Quite simply, a point with higher priority is fixed relative to the other. For instance, imagine that the blue and green time travellers appear in close proximity to each other:

This is a picture where the green time traveller has a higher priority than the blue one. The green arrival changes the timeline (the green cone) and the blue time traveller fits themselves into this new timeline.

If instead the blue traveller had higher priority, we get the following scenario:

Here the blue traveller arrives in the original (white) timeline, fixing their arrival point. The green time traveller arrives, and generates their own future – but this has to be put back into the first white timeline for the arrival of the blue time traveller.

Being close to a time traveller with a high priority is thus very dangerous! The green time traveller may get erased if they don’t flee-at-almost-light-speed.

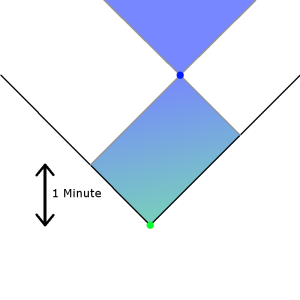

Even arriving after a higher-priority time traveller is very dangerous – suppose that the green one has higher priority, and the blue one arrives after. Then suppose the green one realises they’re not exactly at the right place, and jump forwards a bit; then you get:

(there’s another reason arriving after a higher priority time traveller is dangerous, as we’ll see).

(there’s another reason arriving after a higher priority time traveller is dangerous, as we’ll see).

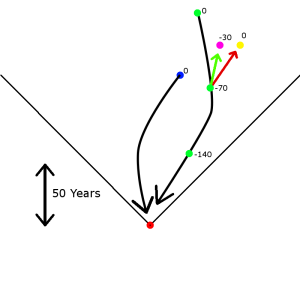

So how do we determine priority? The simplest seems time-space distance. You start with a priority of zero, and this priority goes down proportional to how far your jump goes.

What about doing a lot of short jumps? You don’t want to allow green to get higher priority by doing a series of jumps: This picture suggests how to proceed. Your first jump brings you a priority of -70. Then the second adds a second penalty of -70, bringing the priority penalty to -140 (the yellow point is another time traveller, who will be relevant soon)

This picture suggests how to proceed. Your first jump brings you a priority of -70. Then the second adds a second penalty of -70, bringing the priority penalty to -140 (the yellow point is another time traveller, who will be relevant soon)

How can we formalise this? Well, a second jump is a time jump that would not happen if the first jump hadn’t. So for each arrival in a time jump, you can trace it back to the original jump-point. Then your priority score is the (negative) of the volume of the time-space cone determined by the arrival and original jump-point. Since this volume is the point where your influence is strongest, this makes sense (note for those who study special relativity: using this volume means that you can’t jump “left along a light-beam”, then “right along a light-beam” and arrive with a priority of 0, which you could do if we used distance travelled rather than volume).

Let’s look at that yellow time traveller again. If there was no other time traveller, they would jump from that place. But because of the arrival of the green traveller (at -70), the ripples cause them to leave from a different point in space time, the purple one (the red arrow shows that the arrival there prevents the green time jump, and cause the purple time jump): So what happens? Well, the yellow time jump will still happen. It has a priority of 0 (it happened without any influence of any time traveller), so the green arrival at -70 priority can’t change this fixed point. The purple time jump will also happen, but it will happen with a lower priority of -30, since it was caused by time jumps that can ultimately be traced back to the green 0 point. (note: I’m unsure whether there’s any problem with allowing priority to rise as you get back closer to your point of origin; you might prefer to use the smallest cone that includes all jump points that affected you, so the purple point would have priority -70, just like the green point that brought it into existence).

So what happens? Well, the yellow time jump will still happen. It has a priority of 0 (it happened without any influence of any time traveller), so the green arrival at -70 priority can’t change this fixed point. The purple time jump will also happen, but it will happen with a lower priority of -30, since it was caused by time jumps that can ultimately be traced back to the green 0 point. (note: I’m unsure whether there’s any problem with allowing priority to rise as you get back closer to your point of origin; you might prefer to use the smallest cone that includes all jump points that affected you, so the purple point would have priority -70, just like the green point that brought it into existence).

What other differences could there be between the yellow and the purple version? Well, for one, the yellow has no time jumps in their subjective pasts, while the purple has one – the green -70. So as time travellers wiz around, they create (potential) duplicate copies of themselves and other time travellers – but those with the highest priority, and hence the highest power, are those who have no evidence that time jumps work, and do short jumps. As your knowledge of time travel goes up, and as you explore more, your priority sinks, and you become more vulnerable.

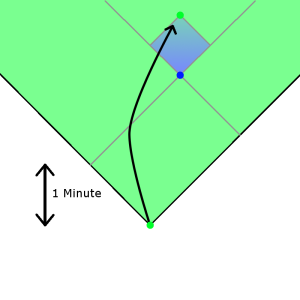

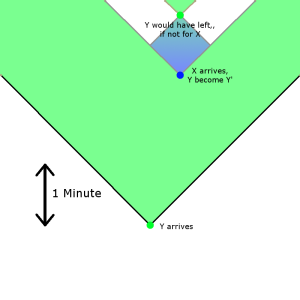

So it’s very dangerous even having a conversation with someone of higher priority than yourself! Suppose Mr X talks with Mrs Y, who has higher priority than him. Any decision that Y does subsequently has been affected by that conversation, so her priority sinks to X’s level (call her Y’). But now imagine that, if she wouldn’t have had that conversation, she would have done another time jump anyway. The Y who didn’t have the conversation is not affected by X, so retains her higher priority.

So, imagine that Y would have done another time jump a few minutes after arrival. X arrives and convinces her not to do so (maybe there’s a good reason for that). But the “time jump in an hour” will still happen, because the unaffected Y has higher priority, and X can’t change that. So if the X and Y’ talk or linger too long, they run the risk of getting erased as they get close to the “point where Y would have jumped if X hadn’t been there”. In graphical form, the blue-to-green square is the area in which X and Y’ can operate in, unless they can escape into the white bands: So the greatest challenge for a low priority time-traveller is to use their knowledge to evade erasure by higher priority ones. They have a much better understanding of what’s going on, they may know where other time jumps likely end up at or start, they might have experience at “rushing at light speed to get out of cone of danger while preserving most of their personality and memories” (or technology that helps them do so), but they are ever vulnerable. They can kill or influence higher priority time-travellers, but this will only work “until” the point where they would have done a time jump otherwise (and the cone before that point).

So the greatest challenge for a low priority time-traveller is to use their knowledge to evade erasure by higher priority ones. They have a much better understanding of what’s going on, they may know where other time jumps likely end up at or start, they might have experience at “rushing at light speed to get out of cone of danger while preserving most of their personality and memories” (or technology that helps them do so), but they are ever vulnerable. They can kill or influence higher priority time-travellers, but this will only work “until” the point where they would have done a time jump otherwise (and the cone before that point).

So, have I succeeded in creating an interesting time-travel design? Is it broken in any obvious way? Can you imagine interesting stories and conflicts being fought there?

This looks like good work, but I will need a little while to carefully work through it all. Until then, please consider reviewing the game “So Now You’re A Time Traveller,” or its longer, more-developed, and out-of-print predecessor “Continuum.”

The combination of your description of the time machine as a ten-meter sphere, and the fact that it fixes the universe at that point reminds me of the holographic principle of string theory where a description of the contents of a black hole are encoded in the event horizon.

Except this is something of an inverse case, where the horizon describes the external past light cone rather than the internal contents.

At least, that’s the techno-babble I’d use. 🙂

Some thoughts about the consequences of your fixed-in-history departure and arrival points:

I recommend playing with a random walk with two absorbing boundaries as a model of history under these constraints (at least that’s my go-to model). This represents the random evolution of the state of history, where the absorbing boundaries are where history becomes canalized into different narratives (representing a large basin of hard-to-distinguish states, from a statistical mechanics perspective). It’s easy to simulate, just discard everything that hasn’t reached the correct boundary at your end time and look at the distribution of the remainder under different drivers. I think it generalizes fairly well to more complicated models.

I end up seeing some interesting features:

1) If the travelers are just tourists (i.e. not trying to modify history), they will see events quickly depart from states where the wrong history will become canalized. But beyond that, actually fixing on the known history happens rather slowly (until you get fairly close to the original departure point). i.e. questions can remain open, group can still know the true history, etc. etc. etc.

2) If the time travelers consistently work towards the wrong historical outcome, the universe will rapidly canalize on the correct outcome (for a variety of statistical reasons involving a biased progression through states). I’ll point out that canalization in this case can also involve the travelers being incarcerated, injured, deprived of their gear, demoralized or dead.

3) The above being said, if the travelers will cease their actions at some point before canalization of the wrong outcome, e.g. at the point where it seems 99% certain that history will go the “wrong” way, then events can react normally to their efforts. This happens when it’s more probably for that 1% chance of the correct outcome is more probable than history resisting their efforts. You could also just see this as another way to canalize the correct history, this time by fooling the time travelers.

4) Finally, time travelers with a powerful ability to influence the course of events can do magic. If they commit themselves to work tirelessly against the correct history if some desired event does not happen, it becomes most probable that said event in fact happens. Of course there’s a dangerous flip side to this in that if it’s more probable that events will conspire to deprive them of their ability to make good on their commitment, then they could face that backlash instead. It’s like the old Mage: The Ascension, except that Paradox is prompt and can happen no matter what who’s watching your magic act.

Basically, you get most of the standard time-travel tropes. Which just indicates that past authors could either program, or were clever enough to see the obvious consequences without needing to justify some enjoyable procrastination.

On a less positive note, I will say I don’t see any distinction between your system and one with fixed history.

Usually systems with fixed history use the “Observer Effect” to cause loopholes, because you haven’t observed history to be precisely what was said in the history books. Likewise in your system, it’s strictly impossible to prove that history used to be different, because all the history books you’ve ever read end up saying exactly what you remember. Either that, or your memory is faulty, and the past is still whatever it was.

Fixed history systems just use epistemic uncertainty to pull the same sort of tricks that you can with nominally changed histories that converge on a fixed point.

Also, your priority system seems to strictly limit what sort of stories you can tell. It’s less a game mechanic than a production rule for describing your fixed history. And that rule means that nobody ever sees time travelers that have made more net jumps than yourself. So time travel must remain a secret history for all time, otherwise those individuals who would have invented a time machine would be affected by travelers who have made a jump and thus are of lower priority.

It also means travelers are strictly forbidden from pulling any Bill&Ted-style hijinks. You can’t go back in time and leave yourself the tools and equipment you need to prevail, because your future self would have a lower priority than your current self, and leaving supplies to allow you victory rather than defeat would certainly change the events surrounding your next departure.

Mind you, if that’s the world you are envisioning, then it’s a very well designed system.

Me? I don’t always travel in time, but when I do, I live to slipshank.