(Originally a twitter thread)

When @fermatslibrary brought up this 1940 paper about why we have nothing to worry about from nuclear chain reactions, I first checked that it was real and not a modern forgery. Because it seems almost too good to be true in the light of current AI safety talk.

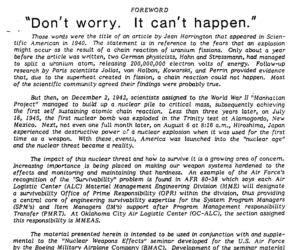

Yes, the paper was real: Harrington, J. (1940). Don’t Worry—it Can’t Happen. Scientific American, 162(5), 268-268.

It gives a summary of a recent fission experiment that demonstrate a chain reaction where neutrons released from a split atom induces other atoms to split. The article claimed this caused widespread unease:

“Wasn’t there a dangerous possibility that the uranium would at last become explosive ? That the samples being bombarded in the laboratories at Columbia University, for example, might blow up the whole of New York City ? To make matters more ominous, news of fission research from Germany, plentiful in the early part of 1 939, mysteriously and abruptly stopped for some months. Had government censorship been placed on what might be a secret of military importance ?

The press and populace, getting wind of these possibly lethal goings-on, raised a hue and cry.”

However, physicists were unafraid to of being blown up (and blowing up the rest of the world).

“Nothing daunted, however, the physicists worked on to find out whether or not they would be blown up, and the rest of us along with them.”

Then comes a good description of the recent French experiment in making a self-sustaining chain reaction. The resulting neutrons are too fast to interact much with other atoms, making the net number dwindle despite a few initial induced fission. And since it runs out, there is no risk.

There are some caveats, but don’t worry, scientific consensus seems to be firmly on the safety side!

“With typical French – and scientific – caution, they added that this was per haps true only for the particular conditions of their own experiment, which was carried out on a large mass of uranium under water. But most scientists agreed that it was very likely true in general.”

This article was 2 years before the Manhattan Project started, so it is unlikely to have been due to deliberate disinformation: it is an honest take on the state of knowledge at the time. Except of course that there was actually a fair bit to worry about soon…

Note that the concern in the article was merely self-sustaining fission chain reactions, not the

atmospheric ignition by fusion discussed later in the Manhattan project and dealt with in the famous (in existential risk circles) report E. J. Konopinski, C. Marvin, and E. Teller, “Ignition of the Atmosphere with Nuclear Bombs,” Los Alamos National Laboratory,

LA-602, April 1946.

The idea that nuclear chain reactions could blow up the world was actually decades old by this time, a trope or motif that had emerged in the earliest years of the 20th century. Given that the energy content in atomic nuclei was known to be vast, that fissile isotopes occur throughout the Earth, and the possibility of a chain reaction at least conceivable after Leo Szilard’s insight in 1933, this was not entirely taken out of thin air.

Human engineering can change conditions *deliberately* to slow down neutrons with a moderator (making a reactor) or use an isotope where hot neutrons cause fission (the atomic bomb). The natural state is not a reliable indicator of the technical state.

It cannot have escaped the contemporary reader that this is very similar to many claims AI will remain safe. It is not reliable enough to self-improve or perform nefarious tasks well, so the chain reaction runs down. Surely nobody can make an AI moderator or find AI plutonium!

More generally, this seems a common argument failure mode: solid empirical evidence against something within known conditions cannot just be extrapolated reliably outside the conditions. What is needed is for the argument to work is (1) the conditions cannot be changed, (2) the result can be smoothly extrapolated, or (3) the impossibility needs to be relevant to the risk.

For nuclear chain reactions both (1) and (2) were wrong (moderators and plutonium). Arguments that AI will always hallucinate may be true, but that does not mean safety follows, since hallucinating humans (the results apply equally to us) are clearly potentially risky.

I think this is a relative to Arthur C. Clarke’s “failure of nerve” (not following extrapolation implications, often leading to overconfident impossibility claims) and “failure of imagination” (not looking outside the known domain or acknowledging there could be anything out there) he discusses in (1982). Profiles of the Future: An Inquiry to the Limits of the Possible.

Also, when reading the article I thought about my discussions with Tom Moynihan about how many tropes are earlier than the discoveries or events enabling them to become real – in the

Scientific American article we already have the planet-destroying explosion and scientists “going dark” for military secrecy.

The funny thing is that this allows enlightened writers to poke fun at those naive people who merely believe in tropes, rather than the real science. The problem is that sometimes we make tropes true.