Yesterday I gave a talk at the joint Bloomberg-London Futurist meeting “The state of the future” about the future of decisionmaking. Parts were updates on my policymaking 2.0 talk (turned into this chapter), but I added a bit more about individual decisionmaking, rationality and forecasting.

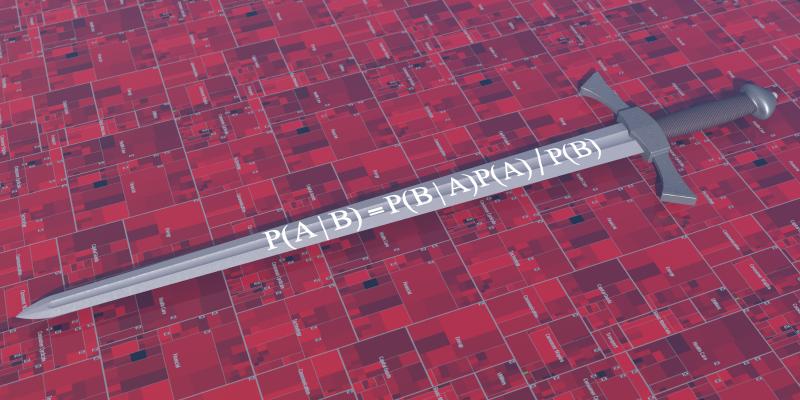

The big idea of the talk: ensemble methods really work in a lot of cases. Not always, not perfectly, but they should be among the first tools to consider when trying to make a robust forecast or decision. They are Bayes’ broadsword:

Forecasting

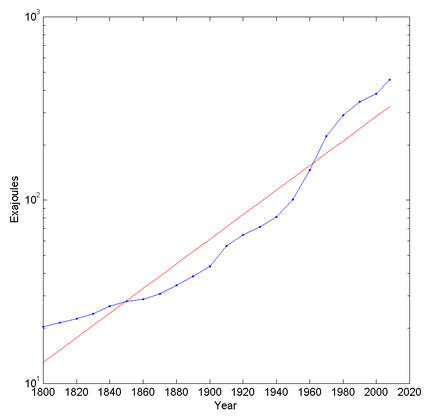

One of my favourite experts on forecasting is J Scott Armstrong. He has stressed the importance of evidence based forecasting, including checking how well different methods work. The general answer is: not very well, yet people keep on using them. He has been pointing this out since the 70s. It also turns out that expertise only gets you so far: expert forecasts are not very reliable either, and the accuracy levels out quickly with increasing level of expertise. One implication is that one should at least get cheap experts since they are about as good as the pricey ones. It is also known that simple models for forecasting tends to be more accurate than complex ones, especially in complex and uncertain situations (see also Haldane’s “The Dog and the Frisbee”). Another important insight is that it is often better to combine different methods than try to select the one best method.

Another classic look at prediction accuracy is Philip Tetlock’s Expert Political Judgment (2005) where he looked at policy expert predictions. They were only slightly more accurate than chance, worse than basic extrapolation algorithms, and there was a negative link to fame: high profile experts have an incentive to be interesting and dramatic, but not right. However, he noticed some difference between “hedgehogs” (people with One Big Theory) and “foxes” (people using multiple theories), with the foxes outperforming hedgehogs.

OK, so in forecasting it looks like using multiple methods, theories and data sources (including experts) is a way to get better results.

Statistical machine learning

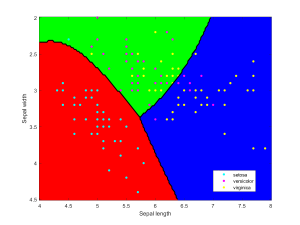

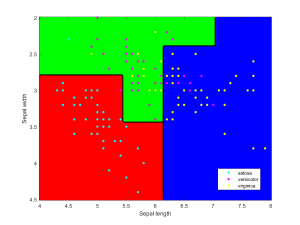

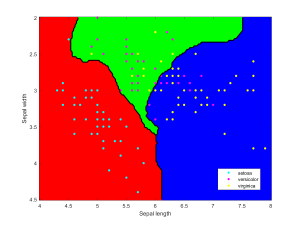

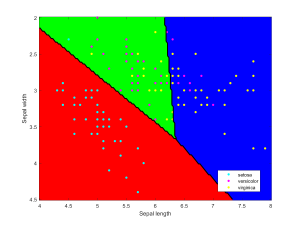

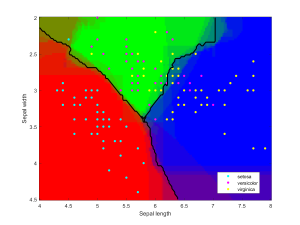

A standard problem in machine learning is to classify something into the right category from data, given a set of training examples. For example, given medical data such as age, sex, and blood test results, diagnose what a particular disease a patient might suffer from. The key problem is that it is non-trivial to construct a classifier that works well on data different from the training data. It can work badly on new data, even if it works perfectly on the training examples. Two classifiers that perform equally well during training may perform very differently in real life, or even for different data.

The obvious solution is to combine several classifiers and average (or vote about) their decisions: ensemble based systems. This reduces the risk of making a poor choice, and can in fact improve overall performance if they can specialize for different parts of the data. This also has other advantages: very large datasets can be split into manageable chunks that are used to train different components of the ensemble, tiny datasets can be “stretched” by random resampling to make an ensemble trained on subsets, outliers can be managed by “specialists”, in data fusion different types of data can be combined, and so on. Multiple weak classifiers can be combined into a strong classifier this way.

The method benefits from having diverse classifiers that are combined: if they are too similar in their judgements, there is no advantage. Estimating the right weights to give to them is also important, otherwise a truly bad classifier may influence the output.

The iconic demonstration of the power of this approach was the Netflix Prize, where different teams competed to make algorithms that predicted user ratings of films from previous ratings. As part of the rules the algorithms were made public, spurring innovation. When the competition concluded in 2009, the leading teams all consisted of ensemble methods where component algorithms were from past teams. The two big lessons were (1) that a combination of not just the best algorithms, but also less accurate algorithms, were the key to winning, and (2) that organic organization allows the emergence of far better performance than having strictly isolated teams.

Group cognition

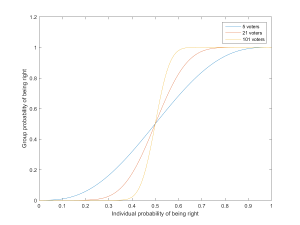

Condorcet’s jury theorem is perhaps the classic result in group problem solving: if a group of people hold a majority vote, and each has a probability p>1/2 of voting for the correct choice, then the probability the group will vote correctly is higher than p and will tend to approach 1 as the size of the group increases. This presupposes that votes are independent, although stronger forms of the theorem have been proven. (In reality people may have different preferences so there is no clear “right answer”)

By now the pattern is likely pretty obvious. Weak decision-makers (the voters) are combined through a simple procedure (the vote) into better decision-makers.

Group problem solving is known to be pretty good at smoothing out individual biases and errors. In The Wisdom of Crowds Surowiecki suggests that the ideal crowd for answering a question in a distributed fashion has diversity of opinion, independence (each member has an opinion not determined by the other’s), decentralization (members can draw conclusions based on local knowledge), and the existence of a good aggregation process turning private judgements into a collective decision or answer.

Perhaps the grandest example of group problem solving is the scientific process, where peer review, replication, cumulative arguments, and other tools make error-prone and biased scientists produce a body of findings that over time robustly (if sometimes slowly) tends towards truth. This is anything but independent: sometimes a clever structure can improve performance. However, it can also induce all sorts of nontrivial pathologies – just consider the detrimental effects status games have on accuracy or focus on the important topics in science.

Small group problem solving on the other hand is known to be great for verifiable solutions (everybody can see that a proposal solves the problem), but unfortunately suffers when dealing with “wicked problems” lacking good problem or solution formulation. Groups also have scaling issues: a team of N people need to transmit information between all N(N-1)/2 pairs, which quickly becomes cumbersome.

One way of fixing these problems is using software and formal methods.

The Good Judgement Project (partially run by Tetlock and with Armstrong on the board of advisers) participated in the IARPA ACE program to try to improve intelligence forecasts. They used volunteers and checked their forecast accuracy (not just if they got things right, but if claims that something was 75% likely actually came true 75% of the time). This led to a plethora of fascinating results. First, accuracy scores based on the first 25 questions in the tournament predicted subsequent accuracy well: some people were consistently better than others, and it tended to remain constant. Training (such a debiasing techniques) and forming teams also improved performance. Most impressively, using the top 2% “superforecasters” in teams really outperformed the other variants. The superforecasters were a diverse group, smart but by no means geniuses, updating their beliefs frequently but in small steps.

The key to this success was that a computer- and statistics-aided process found the good forecasters and harnessed them properly (plus, the forecasts were on a shorter time horizon than the policy ones Tetlock analysed in his previous book: this both enables better forecasting, plus the all-important feedback on whether they worked).

Another good example is the Galaxy Zoo, an early crowd-sourcing project in galaxy classification (which in turn led to the Zooniverse citizen science project). It is not just that participants can act as weak classifiers and combined through a majority vote to become reliable classifiers of galaxy type. Since the type of some galaxies is agreed on by domain experts they can used to test the reliability of participants, producing better weightings. But it is possible to go further, and classify the biases of participants to create combinations that maximize the benefit, for example by using overly “trigger happy” participants to find possible rare things of interest, and then check them using both conservative and neutral participants to become certain. Even better, this can be done dynamically as people slowly gain skill or change preferences.

The right kind of software and on-line “institutions” can shape people’s behavior so that they form more effective joint cognition than they ever could individually.

Conclusions

The big idea here is that it does not matter that individual experts, forecasting methods, classifiers or team members are fallible or biased, if their contributions can be combined in such a way that the overall output is robust and less biased. Ensemble methods are examples of this.

While just voting or weighing everybody equally is a decent start, performance can be significantly improved by linking it to how well the participants perform. Humans can easily be motivated by scoring (but look out for disalignment of incentives: the score must accurately reflect real performance and must not be gameable).

In any case, actual performance must be measured. If we cannot tell if some method is more accurate than something else, then either accuracy does not matter (because it cannot be distinguished or we do not really care), or we will not get the necessary feedback to improve it. It is known from the expertise literature that one of the key factors for it to be possible to become an expert on a task is feedback.

Having a flexible structure that can change is a good approach to handling a changing world. If people have disincentives to change their mind or change teams, they will not update beliefs accurately.

I got a good question after the talk: if we are supposed to keep our models simple, how can we use these complicated ensembles? The answer is of course that there is a difference between using a complex and a complicated approach. The methods that tend to be fragile are the ones with too many free parameters, too much theoretical burden: they are the complex “hedgehogs”. But stringing together a lot of methods and weighting them appropriately merely produces a complicated model, a “fox”. Component hedgehogs are fine as long as they are weighed according to how well they actually perform.

(In fact, adding together many complex things can make the whole simpler. My favourite example is the fact that the Kolmogorov complexity of integers grows boundlessly on average, yet the complexity of the set of all integers is small – and actually smaller than some integers we can easily name. The whole can be simpler than its parts.)

In the end, we are trading Occam’s razor for a more robust tool: Bayes’ Broadsword. It might require far more strength (computing power/human interaction) to wield, but it has longer reach. And it hits hard.

Appendix: individual classifiers

I used Matlab to make the illustration of the ensemble classification. Here are some of the component classifiers. They are all based on the examples in the Matlab documentation. My ensemble classifier is merely a maximum vote between the component classifiers that assign a class to each point.